Lesson Part 1

Parametric Description of Lines in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

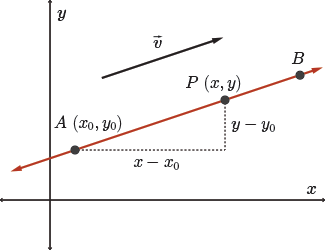

You begin a trip from home, point \( A \), travelling to point \( B \) and you are walking at a constant speed.

Your position, \( P \, (x,y) \), relative to your initial position, \( A \, (x_0, y_0) \), changes over time, \( t \).

Specifically, the \( x \) and \( y \) coordinates of point \( P \) depend on time \( t \), the amount of time that has passed since you left home (point \( A \)).

So in the diagram, we can see here that your horizontal displacement of your walk at time \(t\) is \((x-x_0)\), while your vertical displacement is \((y-y_0)\).

Your velocity, \(\vec{v}\), can be described by the algebraic vector \( \vec{v}=(v_x, v_y) \), where \( v_x \) is the horizontal component of the velocity, and \( v_y \) is the vertical component of your velocity.

Using this information, we can derive a relationship between the \( x \) and \( y \) coordinates and time, \( t \).

So to do that, we consider our distance, speed, time formula. Here we have velocity, so it's a vector. But horizontal velocity is equal to horizontal displacement divided by time. And you can see the set of equations that follow here.

\(\begin{align*} \text{horizontal velocity}&= \text{horizontal displacement} \div \text{time} \\ v_x &= \dfrac{(x - x_0)}{t} \\ v_x t &= x - x_0 \\ \therefore x&= x_0 + v_x t \end{align*}\)

When we simplify and solve for \( x \), we get \( x_0 + v_x t \).

And then we repeat this process, this time for vertical velocity equals vertical displacement divided by time.

\(\begin{align*} \text{vertical velocity}&= \text{vertical displacement} \div \text{time} \\ v_y&= \dfrac{(y - y_0)}{t} \\ v_y t&= y - y_0 \\ \therefore y&= y_0 + v_y t \end{align*}\)

And we simplify the equation, solve for \(y\). We get \( y = y_0 + v_y t \).

These two equations give the position, \( P\,(x, y) \), as a function of a single variable, \( t \).

Now, clearly the position of \(P\,(x,y)\) could be given by a linear function. \(y=mx+b\) comes to mind—it's something that we've used many times in the past—but we have instead expressed both \(x\) and \(y\) in terms of a third variable, \(t\).

When we describe the relationship between two variables (\(x\) and \(y\) in this case) using a third variable (\(t\) in this case), the third variable is called a parameter.

The equations describing the relationship between the two variables and the parameter are known as parametric equations.

Parametric Equations of a Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

In general, the parametric equations of a straight line in a plane are of the form

\[x = x_0 + at\]\[y = y_0 + bt\]

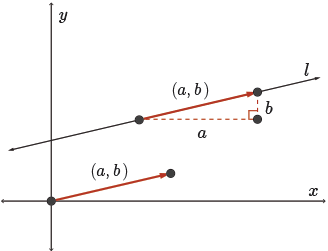

where \((x, y)\) is the position vector of any point on the line, \((x_0, y_0)\) is the position vector of a specific point on the line, and \((a, b)\) is a direction vector of the line; and the parameter \(t \in \mathbb{R}\).

It turns out that each value of \(t\) gives a unique point on the line. And we'll talk more about that later.

Direction Vector of a Line

So the direction vector of a line—what is the direction vector of a line? Well, not surprisingly, for a given line, \(l\), any vector \( \vec{d} = (a, b) \) which is parallel to the line is a direction vector of the line.

Furthermore, the slope of a line with direction vector \( \vec{d} =(a, b) \) is \(m= \frac{b}{a} \), provided \( a \neq 0 \). If \(a=0\), if you think slope—rise over run—then we have a run of 0, which means that the line is vertical, provided \(b \neq 0\).

Parametric equations provide an alternative description of various curves—we'll just concern ourselves with lines here—that could be difficult to express in traditional ways, like in a Cartesian equation form, such as \(y = f(x)\).

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Finally on to some examples. That was a lot of theory, a lot of buildup there. But let's have a look at this example 1. How do we use all this information? What might we be asked to do?

Example 1—Part A

Give a direction vector for a line that passes through the points \( A \, (7, 3) \) and \( B \, (2, 4) \).

Solution

The easiest way to find a direction vector for a line is to find a vector between two points on the line, and as it turns out in this question, we are given just that. We're given two points on the line.

So a direction vector for the line is \( \overrightarrow{AB} \). So tip minus tail. In this manner, \( \overrightarrow{AB} = \overrightarrow{OB} - \overrightarrow{OA} = (2, 4) - (7, 3) = (-5, 1)\) will be a suitable direction vector for this line (or any non-zero scalar multiple of it would also work).

Example 1—Part B

Give a direction vector for a line that has slope \( -\frac{3}{11} \).

Solution

Since slope of a line is defined as \(m=\frac{\mbox{rise}}{\mbox{run}}\), as we mentioned previously, the line with slope \( -\frac{3}{11} \) has a rise of \(-3\) (vertical component) and a run of \(11\) (horizontal component).

Thus, the vector \( (11, -3) \) would serve as a suitable direction vector.

Example 1—Part C

Give a direction vector for a line that is vertical and passes through the point \( (5, 17) \).

Solution

A vertical line has a run of \(0\), so the \( x \)-component of the direction vector will be zero.

Furthermore, any vector of the form \( (0, k), k\neq0\) is parallel to any vertical line, so we can choose whatever \( k \) we want here. Again, \(k\neq0\). But for simplicity, choose \(k=1\). \( (0, 1) \) is a good direction vector for this vertical line, any vertical line.

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Example 2—Part A

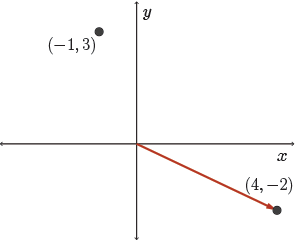

A line with direction vector \( (4, -2) \) passes through the point \( (-1, 3) \). Sketch the line.

Solution

OK. Well, the line passes through this fixed point, \((-1,3)\). So we begin by plotting it. It's easy.

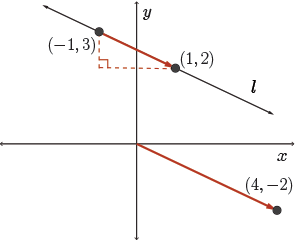

A line with direction vector \(\vec{d}=(4,-2)\) has slope \(m=\frac{-2}{4}=-\frac{1}{2}\).

So we have a point and a slope. Beginning at the point \((-1,3)\) and using \(m=-\frac{1}{2}\), we determine a second point on the line. That is start at \((-1,3)\). Go down \(1\) and right \(2\) to the point \((1,2)\), and then sketch the line, \(l\).

Example 2—Part B

A line with direction vector \( (4, -2) \) passes through the point \( (-1, 3) \). Determine parametric equations of the line.

Solution

We know the general form for parametric equations. All that's required here is for us to substitute in the point that lies on the line.

We just have the one that's given in the question, \((-1,3)\). So we can substitute it in for \((x_0,y_0) \). And our \((a,b)\), or direction vector for the line, is \( (4, -2) \).

We substitute this vector in, and we get the parametric equations for the line.

So the line passing through the point \((-1,3)\) with direction \((4,-2)\) has parametric equations

\(\begin{align*}x&= x_0 + at = -1+4t & \\ y&= y_0 + bt = 3-2t, t \in \mathbb{R} \end{align*}\)

Make sure that at the end of these parametric equations that you do write that \(t \in \mathbb{R}\)—a good practice to put that in.

Example 2—Part C

A line with direction vector \( (4, -2) \) passes through the point \( (-1, 3) \). Determine three other points on this line.

Solution

Well, there are many ways to do this. We have two points already from our sketch. We know that \((-1,3)\) was on the line. We found the \((1,2)\) on the line. We could continue with using the slope to find other points.

Or since we just found the parametric equations (recall that the parametric equations are \(x=-1 + 4t\) and \(y=3-2t\)), then why don't we substitute in different values for \(t\) into the parametric equations? Each value of \(t\) gives a unique point on the line.

So substitute \(t = 1\), for example, into the parametric equations. And we get \((3,1)\).

Substituting \(t=1,2,\) and \(3\), in turn, into the parametric equations of the line gives the \(3\) points: \((3,1), (7,-1), (11,-3)\), each of which lies on the line.

In fact, substitute in \(t\) equals whatever value you want, any real number. We want the points to be different than the ones we already have. So, for example, we don't want to substitute in \(t = 0\), because that gives us the original point that we used from the question: \((-1,3)\).

Example 2—Part D

A line with direction vector \( (4, -2) \) passes through the point \( (-1, 3) \). Does the point \( (-10, 9) \) lie on the line?

Solution

OK, well, again, well, this is a question that we could do using slope and point. But we have these parametric equations. So we'll use them again.

If \( (-10, 9) \) lies on the line, then its components (\(x=-10\) and \(y=9\)) must satisfy the parametric equations simultaneously (at the same time).

\(\begin{align*} x&= -1+4t \\ -10&= -1+4t & \text{substitute the x-coordinate for the point}\\ -9&= 4t \\ t&=- \dfrac{9}{4}\end{align*}\)

And we do the exact same thing for \(y\).

\(\begin{align*} y&= 3-2t \\ 9&= 3-2t \\ 6&= -2t \\ t&=-3\end{align*}\)

And notice what happens here, that we get two different values for \(t\). If \( (-10, 9) \) lies on this line, then these \(t\) values need to be equal. That is, we have a contradiction here.

And it turns out that there is no value of \( t \) such that both components satisfy the parametric equations simultaneously, so \( (-10, 9) \) is not on the line.

Example 2—Part E

A line with direction vector \( (4, -2) \) passes through the point \( (-1, 3) \). Express the equation of the line in \( y = mx + b \) form.

Solution

Well, certainly, we have enough information to do this at this point. This would be a question that now could have done back in grade 9 or 10, easily.

To express the equation of a line in \(y=mx+b\) form given its parametric equations, we have a number of different approaches that we may take.

Method 1

Since we know the slope (we calculated it earlier) is \(m=-\frac12\) and the line passes through the point \((-1,3)\), then substituting these into the general form gives

\(\begin{align*} y&= mx+b \\ 3&= -\frac12(-1)+b \\ b&=\frac52 \end{align*}\)

and so the equation of the line is \(y=-\dfrac12 x+\dfrac52\).

Method 2

Or alternatively, we could use the parametric equations. And how would we do that?

We begin by solving the equation \(x=-1+4t\) for \(t\).

We get

\(\begin{align*} x&= -1+4t \\ 4t&=x+1 \\ t&= \dfrac{x+1}{4} \end{align*}\)

and then we substitute this into the parametric equation for \( y \) and simplify.

Since it's the same value \(t\) in both of the \(x\) and \(y\)-coordinates, then we're able to do this. And we simplify it down into \(y = mx + b\) form again.

\(\begin{align*} y&= 3-2t \\ y&= 3-2\left(\dfrac{x+1}{4}\right) \\ y&= 3 - \frac12 x-\frac12 \\ y&= -\frac 12 x +\frac 52 \end{align*}\)

Therefore, the equation of the line is \( y = -\dfrac 12 x +\dfrac 52 \).

So we get this equation once we substitute in \(t = \dfrac{x+1}{4} \). And sure enough, we get the exact same equation that we did from the first method.

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 3

By placing suitable restrictions on the parameter, use parametric equations to describe the line segment from \(A\,\)(\(-3, -1)\) to \(B\,\) (\(4, 2)\).

So notice that word “segment” in there. We're not talking about the equation of a line now. We're talking about a line segment.

Solution

First, we'll proceed to find the equation of the line. The entire line. Forget the word segment for a moment.

We determine the direction of the line. Well, we have two points on the line. So a direction vector would be given by \(\overrightarrow{AB}\), which is given by \(\overrightarrow{AB}=(7,3)\).

And we have a point on the line. Take your pick. Two choices here. Choose \((4, 2)\). The line passing through the point \((4,2)\) with direction \((7,3)\) has parametric equations

\(\begin{align*} x&= x_0 + at = 4+7t \\ y&= y_0 + bt=2+3t, t\in \mathbb{R} \end{align*}\)

We require the segment of this line for which \(-3 \leq x\leq 4\). Again, I get that from the \(x\)-coordinates of points \(A\) and \(B\) in the question.

That is, we have a line with a fixed domain: \([-3,\ 4]\). Well, we return to the parametric equation for \(x\), that is \(x = 4 + 7t\). So I substitute \(4 + 7t\) in for \(x\) into this inequality. And I solve for \(t\).

\(\begin{align*} -3 &\leq 4+7t \leq 4 \\ -7 &\leq 7t \leq 0 & \text{subtract 4 from all parts of the inequality}\\ -1 &\leq t \leq 0 & \text{divide by 7} \end{align*}\)

Since I'm dividing by a positive, the inequality signs maintain their current direction.

Notice that the restriction on \(y\), \(-1\leq y\leq2\), gives the same restriction on \(t\).

That is, repeat this process with \(y\):

\(\begin{align*} -1 &\leq 2+3t \leq 2 \\ -3 &\leq 3t \leq 0 \\ -1 &\leq t \leq 0 \end{align*}\)

So while this provides a way to check our restriction on \(t\) to make sure that we have it correct, it is not necessary for us to solve both of these inequalities.

The parametric equations for the line segment from \(A\,(-3,-1)\) to \(B\,(4,2)\) are

\(\begin{align*} x&= 4+7t \\ y&=2+3t \text{ for }-1\leq t \leq 0, t\in \mathbb{R}\end{align*}\)

So these \(t\) values are restricting our domain and range so that we just get the segment from \(A\) to \(B\).

Quiz

See the first quiz in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 5

The Vector Equation of a Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

So next we move on to a different form of the equation of a line. It's called the vector equation of a line.

The parametric description of a line

\(\begin{align*} x &= x_0 + at \\ y &= y_0 + bt, \ t \in \mathbb{R} \end{align*}\)

can be combined into a single vector equation

\[ (x, y) = (x_0, y_0) + t(a, b), \ t \in \mathbb{R}\]

where \( (a, b) \) is a direction vector for the line.

Vector Equation of a Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

In general, the vector equation of a straight line in a plane is

\[ \vec{r} = (x_0, y_0) + t(a, b), \ t\in \mathbb{R} \]

where \( \vec{r} = (x, y) \) is the position vector of any point on the line, \( (x_0, y_0) \) is the position vector of a specific point on the line, and \( (a, b) \) is a direction vector of the line, and the parameter \( t \in \mathbb{R} \).

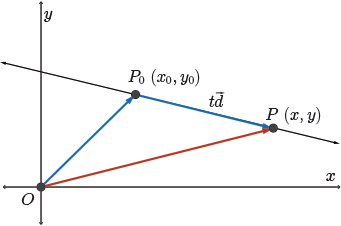

So geometrically, what just happened? Well, the vector equation of the line gives the position vector, \( \overrightarrow{OP} \), of any point, \( P \), on the line (having direction \(\vec{d}=(a, b)\)).

So looking at the diagram here,

\(\begin{align*} \overrightarrow{OP} & = \overrightarrow{OP_0} + \overrightarrow{P_0P} & \text{triangle law of vector addition} \\ \overrightarrow{OP} &= \overrightarrow{OP_0} + t\vec{d} \\ (x, y) &= (x_0, y_0) + t(a, b) \\ \vec{r} &= (x_0, y_0) + t(a, b),\ t\in \mathbb{R} \end{align*}\)

\(\overrightarrow{P_0P}\) is just some appropriate scalar multiple of the direction vector of the line, \(t \vec{d}\).

For which \(t\)? So I mentioned that \(\overrightarrow{OP}= \overrightarrow{OP_0} + t\vec{d}\), so some scalar multiple of \(\vec{d}\), but which scalar multiple of \(\vec{d}\)? What is \(t\)? Well, the truth is \(t\) is any real number. And as we change the value of \(t\), the location of \(P\) changes. And this is the whole idea. \(P\) will stay on the same line, because all we are doing is scaling \(\vec{d}\). But by allowing \(t\) to be all real numbers, we get all possible points \((x, y) \), giving us this entire line.

Lesson Part 6

Examples

Example 4

State a vector equation of the line passing through \( P\, (-4, 6) \) and \( Q\, (2, 3) \).

Solution

Well, we need a direction vector. So \( \overrightarrow{PQ}\) will work. \( \overrightarrow{PQ} = (6, -3) \) is a direction vector of the line.

We need a point on the line. We have our choice of two. Choose \( P\,(-4, 6) \) as a point on the line.

Substitute them into the general form for a vector equation, and a vector equation for the line is

\[ \vec{r} = (-4, 6) + t(6, -3),\ t \in \mathbb{R} \]

Notice that we may also choose \( Q \) as a point on the line.

And in fact, there was no requirement that we use \((6, -3) \) as the direction vector. That was just convenient as we had two points on the line. We could have chosen any non-zero scalar multiple of \(\overrightarrow{PQ}\), say \( \frac13(6, -3)=(2, -1) \), to describe the line.

This gives a completely different looking equation

\[ \vec{r} = (2, 3) + s(2, -1),\ s \in \mathbb{R} \]

which is an equally valid vector equation of the exact same line passing through \( P\, (-4, 6) \) and \( Q\, (2, 3) \).

Note: This demonstrates that the vector equation of a line is not unique; there are infinitely many ways to write a line as a vector equation. And so, too, then are there infinitely many ways to write a line in parametric form.

Example 5

Are the lines \( l_1: \vec{u} = (-1, 1) + s(6, 9) \) and \( l_2: \vec{v} = (-9, -11) + t(-2, -3)\) coincident? (That means are they the exact same line?)

Solution

First, check if the direction vectors are parallel. Clearly, if they aren't parallel, then we don't have to go any further. These lines can't possibly be coincident if they're not parallel.

By inspection, the direction vector for \( l_1 \) is \( (6, 9) = -3(-2, -3)\), so they are scalar multiples of one another and thus the lines are at least parallel to each other.

So now we must continue on. To determine if they are coincident, check if the lines share a common point. Well, they share lots of common points given that they're parallel, but we have to show that they share at least one common point.

The point \( (-1, 1) \) is on \( l_1 \). So the question is does \((-1, 2)\) lie on \( l_2 \)? We substitute this point into \( l_2 \) to check if it satisfies the equation.

\(\begin{align*} (-1, 1)&= (-9, -11) + t(-2, -3) \\ -1&= -9 - 2t & (1) & \hspace{1cm}\text{by equating x-components} \\ 1&= -11 - 3t & (2) & \hspace{1cm}\text{by equating y-components} \end{align*}\)

From this, we solve equation \((1)\) to get \( t = -4 \).

And I guess given our previous example, you're probably guessing that you know what needs to happen here for these two lines to be coincident. That is, we need to solve \((2)\) and get that exact same value for \(t\).

We do this, and sure enough, from equation \((2)\), we also solve to get \(t=-4\).

Hence, there is a value of \( t \) for which \( (-1, 1) = (-9, -11) + t(-2, -3) \), and so \( (-1, 1) \) also lies on \( l_2 \).

Since \( l_1 \) and \( l_2 \) are parallel and share a common point, then they must be coincident.

Well, that's the end of this module. I thank you for listening. We will move on in the next module and have a look at the scalar equation of a line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

Quiz

See the second quiz in the side navigation.