Lesson Part 1

Introduction

Calculus, specifically the derivative, is a crucial tool for understanding relationships involving change.

Calculus is used in physics, chemistry, biology, and economics, where rates of change are extensively studied.

Understanding rates of change enables experts to make reasonably accurate predictions about various phenomena.

Thus, the definition of a derivative as an instantaneous rate of change has many uses in real world applications.

Rates of change exist in many forms throughout the physical world:

- Physics (Speed)—change in distance with respect to time. In general, we look at rates of change in terms of motion.

- Chemistry and Industry (Filling and Draining Rates)—change in volume with respect to time

- Construction and Infrastructure—change in area with respect to time

- Economics—changes in profit with respect to cost

- Biology (Population Dynamics)—change in predator population with respect to a prey's population

- Medicine (Oncology and Infectious Diseases)—change in tumour size over time; growth of epidemics

And, of course, there are many more.

Example 1

At a winter fair, a cube of ice with \(1\) metre side length melts in the daytime sun. Its volume, in cubic metres, at \(t\) hours is given by \(V(t)=-\frac{1}{540}t^3+1\) m\(^3\).

Notice how here we've used \(V\) to represent the volume of the ice and \(t\) to represent the time as the volume of ice melts.

Example 1—Part A

Determine an equation that will calculate the instantaneous rate of change of the volume of the ice cube with respect to time, \( t \).

Solution

We will use the derivative.

The derivative of a function represents the instantaneous rate of change of the dependent variable with respect to the independent variable.

So, the equation that calculates the instantaneous rate of change of the volume of the cube with respect to time is \(V'(t)=-\frac{1}{180}t^2\) m\(^3\)/h.

Now that we have a general equation which will calculate the instantaneous rate of change, we can do so for any particular time.

Example 1—Part B

How fast is the volume of the ice cube changing \(3\) hours after it is placed outside?

Solution

Since we're looking at three hours after it is placed outside, we will substitute \(t=3\) into the formula for the instantaneous rate of change: \(V'(t)=-\frac{1}{180}~t^2\) m\(^3\)/h.

\[\begin{align*}V'(3) & =-\frac{1}{180}(3)^2 \\ &=-\frac{1}{20} \text{ m}^3\text{/h}\end{align*}\]

After we calculate this, we see that the volume of ice is changing at \(\frac{1}{20}\) of a cubic meter per hour. Since there is a negative sign attached to this value, we know \(V'(3)=-\frac{1}{20}\) m\(^3\)/h \(\lt0\). This means that the volume of the cube is decreasing three hours after the ice is put into the sun.

Example 1—Part C

When will the ice cube have completely melted? How fast was the ice cube melting just before it melted completely?

Solution

To calculate when the ice cube will have completely melted, we want the volume to be equal to zero. That is, the ice cube will have completely melted when \(V(t)=0\).

Once we substitute \(V=0\) into our equation, we can now solve for \(t\) to find the time when the volume will be zero:

\[\begin{align*}V(t)&=-\frac{1}{540}t^3+1 \\0 &=-\frac{1}{540}t^3+1 \\ t^3 &=540 \\ t &=\sqrt[3]{540}\approx 8.14 \text{ hours} \end{align*}\]

In this case, solving for \(t\) tells us that the ice will have melted completely at approximately \(8.14\) hours after the cube of ice is placed in the sun.

To determine how fast the ice cube was melting just before it vanished, substitute \(t=8.14\) into the formula for the instantaneous rate of change, \(V'(t)=-\frac{1}{180}t^2\), to determine how fast the ice cube was melting at that point.

\[\begin{align*}V'(8.14) &=-\frac{1}{180}(8.14)^2 \\ &=-0.37 \text{ m}^3\text{/h}\end{align*}\]

Thus, the ice cube will have completely melted approximately \(8.14\) hours after being taken outside and it was melting at a rate of \(0.37\) m\(^3\)/h just before it vanished.

Lesson Part 2

Example 2

In a town, the population, \(P(t)\), of raccoons \(t\) years after the beginning of the year 2000 is modelled by \(P(t)=0.04t^3+0.7t^2-2t+35\).

For example, at the beginning of 2001, the population was approximately \(P(1)=33.74\).

Now, notice here that we are modelling the population growth of raccoons using a polynomial function, which is continuous. Strictly speaking, this is not quite correct, because population growth cannot be continuous. Really, the population would jump up or down discretely whenever there is a birth or a death. So this function is a continuous approximation of the growth.

For example, the function value, \(P(1)=33.75\), doesn't mean that there are \(33\) and \(\frac{3}{4}\) raccoons after one year. In other words, we're not saying that we're counting partial raccoons in the population. It means that there are approximately \(34\) raccoons in the population at this time.

We use a continuous approximation in order to talk about instantaneous growth rates. In fact, we need a differentiable function in order to apply our calculus tools. So let's answer some questions about the growth of this population.

Example 2—Part A

Given \(P(t)=0.04t^3+0.7t^2-2t+35\), how quickly was the population of raccoons changing at the start of 2010?

Solution

We are looking for the instantaneous growth rate of the raccoon population at the start of 2010.

Since the model is continuous and differentiable, we can find the instantaneous rate of change of the raccoon population at time \(t\) by differentiating \(P(t)\). Differentiating with respect to time, we have

\[P'(t)=0.12t^2+1.4t-2\]

This is our formula for the instantaneous rate of change.

Since the beginning of 2010 is \(10\) years after the beginning of 2000, we can find \(P'(10)\) to determine how the population was changing at the start of 2010. Substituting \(t = 10\) into the expression for the derivative gives

\[\begin{align*} P'(t) & =0.12t^2+1.4t-2 \text{ raccoons per year} \\ P'(10) & =0.12(10)^2+1.4(10)-2 \\ & =24 \text{ raccoons per year}\end{align*}\]

Therefore, the instantaneous rate of change of the population at the start of 2010 was \(24\) raccoons per year.

So how do we interpret this numerical result? This does not mean that the population gained \(24\) raccoons at the start of 2010. It means that, at this exact instant, the population was growing at a rate of approximately \(24\) raccoons per year.

Another way to think about that is, if the growth rate remained constant at this rate for the entire year, then the population would have \(24\) more raccoons at the end of 2010. Again, since this is only an approximation, it is possible here to get a rate of change that's not even an integer. As before, a derivative value of, say, \(P'(t)=5.25\), should be interpreted as increasing by approximately \(5\) raccoons per year.

Example 2—Part B

Given \(P(t)=0.04t^3+0.7t^2-2t+35\), when was the population of raccoons increasing by \(10\) raccoons per year?

Solution

In this case, we know the rate of change of the raccoon population.

Here, we must find when \(P'(t)=10\).

Substituting the value of \(10\) into our derivative function, we can now rearrange and simplify this equation to receive the following quadratic equation:

\[\begin{align*}P'(t) & =0.12t^2+1.4t-2 \\ 10 &=0.12t^2+1.4t-2 \\ 0 &=0.12t^2+1.4t-12 \\ 0 & =3t^2+35t-300 \end{align*}\]

We simplified this by multiplying both sides by \(25\).

Now, this quadratic equation does not factor nicely, so let's use the quadratic formula to help us solve this quadratic equation:

\[\begin{align*} t & =\dfrac{-35\pm \sqrt{35^2-4(3)(-300)}}{2(3)} \\ & =\dfrac{-35\pm \sqrt{4825}}{6} \\ & =\dfrac{-35\pm 5\sqrt{193}}{6}\end{align*}\]

Within this expression, there are two values of \(t\), there is a positive value and a negative value if we were to evaluate them.

However, our model says \(t\gt0\), so we only need to consider the positive value of \(t\). Thus, we have \(t=\dfrac{-35+ 5\sqrt{193}}{6} \approx 5.74\) years.

Therefore, roughly, at \(5\frac{3}{4}\) years after 2000, around the beginning of September in 2005, the population was increasing by \(10\) raccoons per year.

Example 2—Part C

Recall \(P(t)=0.04t^3+0.7t^2-2t+35\). During one year, food for the raccoons became scarce and the population was at a minimum. In what year did this occur?

Solution

In previous modules, we saw that a local minimum value occurs when the derivative is equal to \(0\). So in this case, we are going to let \(P'(t)=0\) and solve for the corresponding \(t\).

Substituting \(0\) into the formula for the derivative and simplifying this, we again receive a quadratic equation:

\[\begin{align*}P'(t) & =0.12t^2+1.4t-2 \\ 0 &=0.12t^2+1.4t-2 \\ 0 & =3t^2+35t-50 \end{align*}\]

We simplified this by multiplying both sides by \(25\).

Once again, this quadratic equation cannot be factored nicely, so we'll use the quadratic formula to help us find the value of \(t\).

\[\begin{align*} t & =\dfrac{-35\pm \sqrt{35^2-4(3)(-50)}}{2(3)} \\ & =\dfrac{-35\pm \sqrt{1825}}{6} \\ & =\dfrac{-35\pm 5\sqrt{73}}{6} \\ \end{align*}\]

Again, we know that \(t\gt 0\), so we only need to consider the positive value of \(t\) that the quadratic formula produces. Thus, the population must have been at a minimum when \(t=\dfrac{-35+ 5\sqrt{73}}{6}\approx 1.29\) years.

Therefore, during April 2001 the population of raccoons was at a minimum. Note that we can verify that this critical point is indeed a local minimum by using the first or second derivative test.

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Now that we have looked at a few applications of the derivative, let's try a more challenging question.

Challenge Question

Consider the triangle formed between the coordinate axes and the tangent line to any point \((a,b)\) on the graph of \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}\), \(x\ne0\). Prove that the area of this triangle will always be \(2\).

Question taken from: Malinowski, R., Murray, D., Shifrin, J., Wilson, L. (2002). Harcourt Mathematics 12: Advanced Functions and Introductory Calculus. Toronto, ON: Harcourt Canada Limited.

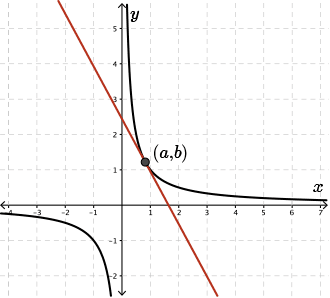

Now, recall the graph of \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{x}\) has a vertical asymptote at \(x= 0\), hence why we will consider the restriction \(x \neq 0\).

Solution

Before tackling this problem, it's probably a good idea to make a sketch so that we can visualize what we are talking about.

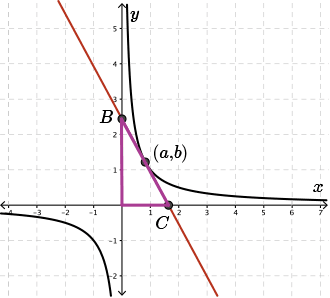

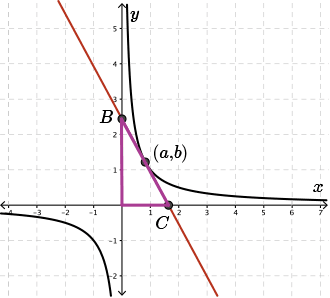

On the axes you will see the graph of \(\dfrac{1}{x}\) drawn. Let's plot any point, \((a,b)\), on this graph and draw the tangent at this point.

Notice how the tangent intersects the \(x\)- and \(y\)-axes at two other points. Now we have a triangle. The triangle vertices are the origin, point \(B\), and point \(C\).

Since \(x\ne0\), then we know that the \(a\) coordinate of the point of tangency cannot be \(0\). That is, \(a\ne0\). This will help us as we move through the algebra of this question.

Our first step in proving that the triangle formed has an area of \(2\) will be to find an equation that represents the tangent line.

To make the equation of the tangent line, we must first start at finding its slope. The slope of the tangent is equal to the derivative of our function.

\[m_{\textrm{tangent}}=f'(x)\]

Before we differentiate the function \(\dfrac{1}{x}\), let's express it with a negative exponent to make the differentiation simpler.

\[\begin{align*}m_{\textrm{tangent}} & =(x^{-1})' \\ & =-x^{-2} \\ & =-\dfrac{1}{x^2}\end{align*}\]

after putting this back into its fractional form.

Since the tangent line is drawn at the point \((a, b)\), we know that the value of \(x\) in this case is equivalent to \(a\). Let's substitute \(a\) into our derivative function to get an expression for the slope of the tangent at point \((a, b)\).

Thus,

\[f'(a)=-\dfrac{1}{a^2}\]

Now, when \(x=a\), \(f(a)=\dfrac{1}{a}\). Therefore, \(b=\dfrac{1}{a}\), where \(a\ne0\).

So, rather than saying that the point of tangency is \((a, b)\), instead we could say that the point of tangency is \(\left(a, \dfrac{1}{a}\right)\), where \(a \neq 0\).

We have a point that is on the tangent line and we know its slope. So, using the slope-point equation of the line, \(m(x-x_1)=y-y_1\), with \(x=a\), \(y=\dfrac{1}{a}\), and \(m=-\dfrac{1}{a^2}\), the tangent drawn to the point \(\left(a,\dfrac{1}{a}\right)\) has equation

\[\begin{align*} -\dfrac{1}{a^2}(x-a) & =y-\dfrac{1}{a} \\ x-a & =-a^2\left(y-\dfrac{1}{a}\right) \\ x-a & =-a^2y+a \\ x+a^2y-2a & =0 \end{align*}\]

Rearranging the equation and simplifying, the equation of the tangent line at the point \((a,b)\) is \(x+a^2y-2a=0\). This is the equation of the tangent line at any point along this curve.

Now, let's consider the triangle again that's in our diagram.

The base of the triangle is the value at which the tangent crosses the \(x\)-axis (point \(C\)) and the height is the value at which the tangent crosses the \(y\)-axis (point \(C\)).

So, if we know the equation of the tangent line and we find its \(x\)- and \(y\)-intercept, we have the point where the tangent crosses these axes.

The tangent line crosses the \(x\)-axis when \(y=0\). Substituting \(0\) into our equation of a line, we get

\[\begin{align*}x+a^2(0)-2a &= 0 \\ x &= 2a \end{align*}\]

The tangent line crosses the \(y\)-axis when \(x=0\),

\[\begin{align*} (0)+a^2y-2a &= 0 &\\ a^2y & =2a & \\ y & =\dfrac{2a}{a^2} & \text{ where } a\ne 0 \\ y & =\dfrac{2}{a} & \text{ because } a\ne0\end{align*}\]

Summarizing:

- The tangent line crosses the \(x\)-axis when \(x=2a\).

- The tangent line crosses the \(y\)-axis when \(y=\dfrac{2}{a}\).

So, we now know the base and height of the triangle. And so we can use these in the formula that calculates the area of the triangle.

The area of the triangle formed by the tangent through any point \((a,b)\) on the curve \(y=\dfrac{1}{x}\), and the coordinate axes is

\[\begin{align*}A &= \dfrac{1}{2}\left(2a\right)\left(\dfrac{2}{a}\right) \\& = 2\end{align*}\]

because \(a\ne0\).

Quiz

See the first quiz in the side navigation.