Lesson Part 1

Examples

Example 1

Let's start right off with an example. Given the line \( y = -\frac{2}{3}x + 5 \), find a vector equation and parametric equations describing the line.

Solution

So we start right off with an example because this is a problem that we did last module.

Since the slope is \( -\frac{2}{3} \), we may choose direction vector \( \vec{d} = (3, -2) \).

A point on the line is \( (0, 5) \) (conveniently, the \( y \)-intercept), and so the vector equation is \( \vec{r} = (0, 5) + t(3, -2),~t \in \mathbb{R}\) and separating this vector equation into its parametric equations, we get \(x = 3t\) and \(y = 5 - 2t, ~ t \in \mathbb{R}\).

The above example shows the standard method for finding the vector/parametric equations of a line.

As we saw in the previous module, we may be required to go in the opposite direction to find the Cartesian equation of a line given the vector/parametric equations.

Method 3

So we worked through two methods for doing this in the last module. Let's look at yet another possibility.

Solve each of the parametric equations for \(t\) to get \( t = \dfrac{x}{3} \) and \( t = -\dfrac{y - 5}{2} \).

And again, \(t\) is equal to \(t\). So we set these equal to one another and we get an equation in \(x\) and \(y\) and we simplify it:

\(\begin{align*} t&=t \\ \dfrac{x}{3}&= -\dfrac{y - 5}{2} \\ -2x&= 3y - 15 \\ 0&= 2x + 3y - 15 \end{align*}\)

We can only solve for \( t \) this way if the direction vector, \( \vec{d} \), has non-zero components. And we did divide by the components of \( \vec{d} \) here, so we need them to be non-zeros in the denominators.

This form of the equation is called the scalar equation of a line in \( \mathbb{R}^2 \) (\(2\)-space). And we will define this scalar equation of a line a little more formally in a few moments here.

Let's have a look at this line \(2x + 3y - 15\). And specifically, let's consider the coefficients of \(x\) and \(y\) in the scalar equation \( \textcolor{Mulberry}{2}x + \textcolor{Violet}{3}y - 15 = 0 \).

Define a vector \( \vec{n} = (\textcolor{Mulberry}{2}, \textcolor{Violet}{3}) \) (formed by taking these highlighted coefficients in the scalar equation). Now, you're probably thinking, why would I do that? Well, bear with me for a moment.

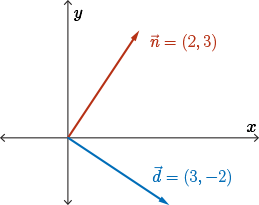

Graph vector \(\vec{n}=(2,3)\) along with the direction vector for the line, \(\vec{d}=(3,-2)\), on the same \(xy\)-plane.

So I'm looking at this graph. And wow, those two vectors, \( \vec{d} \) and \( \vec{n} \), they look to be orthogonal (perpendicular). I don't know that they are. I mean, it looks close. But I know how to check.

If I have two vectors and I want to know if they're perpendicular, well, I can take their dot product.

\[ \vec{d} \cdot \vec{n} = (3, -2) \cdot (2, 3) = 6-6=0 \]

Hence, the two vectors are indeed orthogonal.

In fact, I didn't just pull \( \vec{n} \) out of nowhere. This vector is a special vector, and it has a special name: The vector \( \vec{n} \) is known as a normal vector.

Definition

A normal vector to a line is a vector, \( \vec{n} \), which is orthogonal to the direction vector, \( \vec{d} \), of the line.

Lesson Part 2

Scalar Equation of a Line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\)

So now it's time to more formally define the scalar equation of a line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\).

The scalar equation of a straight line in a plane is given by \(Ax+By+C=0\) where \(\vec{n}=(A,B)\) is a normal vector to the line.

So we only looked at one specific example and then we claimed that the line \(Ax+By+C=0\) has this normal, \(\vec{n}=(A,B)\). Well we better show that this is actually the case. Well how would we do that?

Since the normal vector is orthogonal to the line, it is orthogonal to any arbitrary segment of the line as well.

For an arbitrary line, let \( \vec{n} = (A, B) \) be a normal vector to the line.

If \( P_0\,(x_0, y_0) \) is a fixed point on the line, and \( P\,(x, y) \) is any arbitrary point on the line (distinct from \(P_0\)), then \( P_0P \) is a line segment. In fact, we can get the direction of the line. It would be \(\overrightarrow{P_0P}\). Thus, the normal vector \(\vec{n}=(A, B)\) is orthogonal to \(\overrightarrow{P_0P}\), and so

\(\begin{align*} \vec{n} \cdot \overrightarrow{P_0P}&= 0 \\ (A, B) \cdot (x - x_0, y - y_0)&= 0 & \text{tip minus tail}\\ A(x - x_0) + B(y - y_0)&= 0 \\ Ax - Ax_0 + By - By_0&= 0 \\ Ax + By - (\underbrace{Ax_0 + By_0}_{\text{constant}})&= 0 & a, b, x_0, y_0 \text{ are scalar}\\ \therefore Ax + By + C&= 0 \end{align*}

\)

where \(A\) and \(B\) are the components of the normal vector and \( C = -(Ax_0 + By_0) = -(\vec{n} \cdot \overrightarrow{OP_0}) \), a constant.

This is the scalar equation of a line in \(\mathbb{R}^2\) with normal vector \( (A, B) \).

The above derivation illustrates a useful fact about the normal vector.

If we know the coordinates of the normal vector \( (A, B) \) to a line, and the coordinates of a specific point \( P_0\,(x_0, y_0) \) on the line, we can quickly find the scalar equation \( Ax + By + C = 0 \).

How so? How would that work? Well let's go back to our previous example.

Examples

Example 1 Revisited

Given the line \( y = -\frac{2}{3}x + 5 \), find a vector equation and parametric equations describing the line.

Solution

In our example, \( \vec{d} = (3, -2) \).

By inspection, a normal vector is \( \vec{n} = (2, 3) \). And we can check that that works. Again, we just take \( \vec{d} \cdot \vec{n} \) and make sure it's equal to \(0\). So 2 comma 3 is certainly the normal vector. Any non-zero scalar multiple of \((2,3)\) would also work. So we have the normal vector.

Since \((0,5)\) lies on the line, substitute the point and \(\vec{n}\) into \(Ax + By + C = 0\) and solve for \(C\). Then \(2x+3y+C=0\) becomes \(2(0) + 3(5) + C = 0\) and so \(C=-15\).

Therefore, the scalar equation of the line is \(2x+3y-15=0\) which confirms what we previously determined.

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Let's look at another, new example.

Example 2

Given \( \vec{r} = (7, -1) + t(4, 3), ~ t \in \mathbb{R}\), find the scalar equation of the line.

Solution

Well, very quickly from the vector equation, the line has direction \( \vec{d} = (4, 3) \) and passes through \(P_0\,(7,-1)\).

So if I look at the direction vector, \((4, 3)\), I can quickly by inspection get a vector perpendicular to it: \( \vec{n} = (3, -4) \) is a normal vector to the line (since \(\vec{d}\cdot\vec{n}=0)\).

Again, notice what I have to do here. All I have to do is switch the \(x\) and \(y\) components of the direction vector and negate one of them, and I have the normal vector. But again it's always good practice to check that this dot product of these two vectors is indeed \(0\).

The scalar equation is of the form \( 3x - 4y + C = 0 \). That is we take our normal vector \((3, -4) \), and we substitute in for \(A\) and \(B\).

Further, substituting \( P_0\,(7, -1) \), the specific point that this line passes through, and solving for \(C\) gives \( 3(7) - 4(-1) + C = 0\) and so \(C=-25\).

Therefore, the scalar equation of the line is \(3x - 4y - 25 = 0 \).

Example 3

Find the vector equation of the line \( 4x - 7y + 12 = 0 \).

Solution

So this time we're asked to go in the opposite direction. We're given the scalar equation of a line. We're asked for the vector equation.

By inspection, \( \vec{n} = (4, -7) \). The coefficient of the \(x\) term and the coefficient of the \(y\) term — there's our normal vector. And so again, by inspection, we can come up with a direction vector. Switch the \(x\) and \(y\) components and negate one of them, we get \( \vec{d} = (7, 4) \). And check it. \(28 - 28 = 0\). Good.

Now all we need is a point on the line. Letting \( y = 0 \) and solving for \(x\), the equation of the line becomes \( 4x + 12 = 0 \), so \( x = -3 \).

Thus, a point on the line is \( P_0\,(-3, 0) \), and so a vector equation is

\[ \vec{r} = (-3, 0) + t(7, 4),~t \in \mathbb{R} \]

Example 4

Find the obtuse and acute angles between the lines \(l_1: -2x+5y-7=0 \) and \(l_2: 6x+y-4=0\).

Solution

Well it turns out that the angle between any pair of lines is also the angle between their normal vectors. Does this make sense? Can you prove this?

It would be a good exercise. At the very least, you should be able to draw a picture of this for yourselves. Draw any two lines. Draw normal vectors to the lines. And see if you can at least confirm this for yourself in your mind that this would be the case that the angle between two lines is equal to the angle between their normal vectors. At any rate, we'll leave that as an exercise. Let's proceed.

The normal vector for \(l_1\) is \(\vec{n_1}=(-2,5)\), and the normal vector for \(l_2\) is \(\vec{n_2}=(6,1)\). Again, just taking the coefficients from the scalar equations.

And so we want to find the angle between these two normal vectors. Well, this is a problem that we have done a few times now.

Using the equivalent forms of the dot product, we have

\(\begin{align*}\vec{n_1} \cdot \vec{n_2}&= \lvert\vec{n_1}\rvert\lvert\vec{n_2}\rvert\cos(\theta) & \text{theta is the angle between the 2 normals}\\ (-2,5) \cdot (6,1)&= \lvert(-2,5)\rvert\lvert(6,1)\rvert\cos(\theta) \\ -12+5&= \sqrt{29}\sqrt{37}\cos(\theta) \\ -\dfrac{7}{\sqrt{29}\sqrt{37}}&= \cos(\theta) \\ \theta&=\cos^{-1}\left(-\dfrac{7}{\sqrt{29}\sqrt{37}}\right) \\ \therefore \theta&\approx 102.3^{\circ}\end{align*}\)

Therefore, the angle between the normals \(\vec{n_1}\) and \(\vec{n_2}\) is approximately \(102.3^{\circ}\) and so the obtuse and acute angles between the two lines are approximately \(102.3^{\circ}\) and the supplement of that which is \(180^{\circ}-102.3^{\circ}=77.7^{\circ}\).

So that's it for this module. It was a nice quick short one. Next up we'll look at equations of lines, but this time will move into the third dimension, \(\mathbb{R}^3\). Thanks for listening.

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.