Lesson Part 1

Intervals of Concavity

In the previous module, we examined the graph of \(y= f(x)=x^3\) and saw that this function is increasing throughout its domain.

Although the graph is increasing for \(x\lt 0\) and for \(x\gt 0\) we notice that the shape of the curve is very different within these two intervals.

Once again, let's examine the slope of the tangent at points along the curve.

When \(x \gt 0\), the curve lies above the tangent line, bending upwards.

Mathematicians use the term concave upward to describe this property.

However, when \(x \lt 0\), the curve lies below the tangent line, bending downwards.

Mathematicians use the term concave downward to describe this property.

A point where an unbroken curve changes from concave upward to concave downward or vice versa is called a point of inflection.

As the point of tangency moves from left to right along the curve, we notice that the slope of the tangent line decreases as \(x\) approaches \(0\) from the left, whereas the slope of the tangent line increases as the point moves right from \(x=0\).

Since we see that the slope of the tangent changes along the curve, let's examine the rate of change of the slope of the tangent by examining the graph of \(f'(x)\).

The first derivative of \(f(x)=x^3\) is \(f'(x)=3x^2\).

Let's examine the behaviour of the first derivative curve to see the connection to the intervals of concavity.

Consider a tangent line drawn at any point on the graph of the first derivative curve \(y=f'(x)=3x^2\).

As the point of tangency moves from left to right along the first derivative curve, we notice that the slope of the tangent line is negative but continually decreases in steepness (i.e., becomes less negative) as \(x\) approaches \(0\) from the left.

As the point of tangency moves right of \(x=0\), the slope of the tangent line becomes positive and increases in steepness.

The second derivative calculates the rate of change of the slope of the tangent to the first derivative curve.

Therefore, for \(\textcolor{NavyBlue}{x\gt 0}\) we have \(f''(x)=6x\gt 0\), so the graph of \(f(x)\) is concave upward. For \(\textcolor{Mulberry}{x\lt 0}\), we have \(f''(x)=6x\lt 0\), so the graph of \(f(x)\) is concave downward.

Definitions

Suppose a function, \(f\), is twice differentiable (i.e., we can find its second derivative) on the interval \(a\lt x\lt b\).

A graph, \(y=f(x)\), is concave upward on the interval \(a\lt x\lt b\) if \(f''(x)\gt 0\) (i.e., positive) for \(a\lt x\lt b\). Graphically, the curve \(y=f(x)\) lies above the tangent line at each point in the interval \(a\lt x\lt b\).

A graph, \(y=f(x)\), is concave downward on the interval \(a\lt x\lt b\) if \(f''(x)\lt 0\) (i.e., negative) for \(a\lt x\lt b\). Graphically, the curve \(y=f(x)\) lies below the tangent line at each point in the interval \(a\lt x\lt b\).

Assuming that the function is continuous (i.e., the graph of the function is unbroken), a point of inflection separates an interval where the curve is concave upward from an interval where the curve is concave downward.

If \(f''\) exists at a point, \(x=c\), where the concavity changes, then \(f''(c)=0\). If \(f''(c)\) exists, then \(f'(c)\) must also exist.

Therefore, a tangent line will exist at the point of inflection.

The curve \(y=f(x)\) will cross the tangent line at this point of inflection.

Note:

Not all values of \(x\) having \(f''(x)=0\) will be points of inflection. Once we find values of \(x\) having \(f''(x)=0\), we must then check if \(f''(x)\) changes its sign at that value of \(x\) to determine the existence of a point of inflection.

We must also check this for any points where \(f'(x)\) or \(f''(x)\) is undefined, since they may also separate intervals of concavity. Again, we check these points by examining if \(f''(x)\) changes its sign at that value of \(x\).

Lesson Part 2

Examples

The following three examples illustrate why we must check if \(f''(x)\) changes sign at a point \(x=c\) where \(f'(c)\) or \(f''(c)\) does not exist, since this point may be a point where the concavity changes.

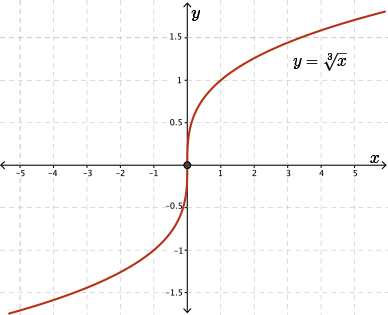

Example 1

Consider \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\) for which \(f'(x)=\dfrac{1}{3x^{\frac{2}{3}}}\).

At \(x=0\), \(f'(x)\) does not exist, since we would have division by \(0\). Therefore, \(f''(x)\) cannot exist for \(x=0\) either.

However, when we look at the graph of \(f(x)=\sqrt[3]{x}\), we see that, at \(x=0\), there exists a point of inflection.

On the left side of the graph, we see that this curve is concave upwards. The right side of this graph is concave downwards. And the point where we change from concave upwards to downwards is at \(x=0\).

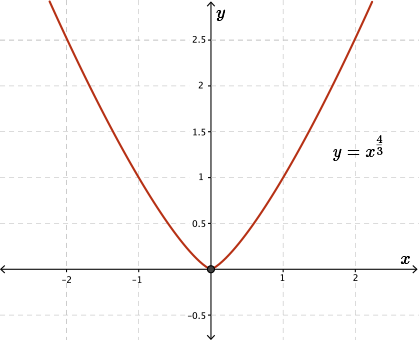

Example 2

Here is another case to consider. Let's look at the graph of \(f(x)=x^{\frac{4}{3}}\). The first derivative of this function is \(f'(x)=\dfrac{4}{3}x^{\frac{1}{3}}\) and \(f''(x)=\dfrac{4}{9x^{\frac{2}{3}}}\).

In this case, \(f''(0)\) does not exist since if we were to substitute \(x=0\) into this expression, again we would have division by \(0\). So we cannot find the value of \(f''(0)\).

However, when we do graph \(f(x)=x^{\frac{4}{3}}\), we see that the graph on the left side of \(x = 0\) is concave upwards. And we see that the graph on the right side of \(x = 0\) is also concave upwards. In this case, the second derivative does not exist at \(x = 0\), and at \(x = 0\) there is no point of inflection. This is unlike the last example that we saw.

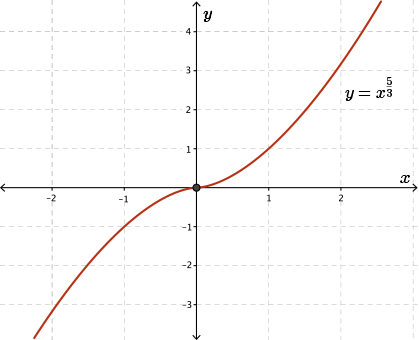

Example 3

Finally, let's consider one more graph. Examine the graph of \(f(x)=x^{\frac{5}{3}}\) for which \(f'(x)=\dfrac{5}{3}x^{\frac{2}{3}}\) and \(f''(x)=\dfrac{10}{9x^{\frac{1}{3}}}\).

Again, in this case, \(f''(0)\) does not exist, since we would have division by \(0\) in the expression.

But by inspecting the graph, we see that at \(x = 0\) there is a point of inflection. The left side of this graph is concave downwards. The right side of this graph is concave upwards. And the graph changes from concave downwards to concave upwards at the point \(x = 0\).

Polynomial Functions

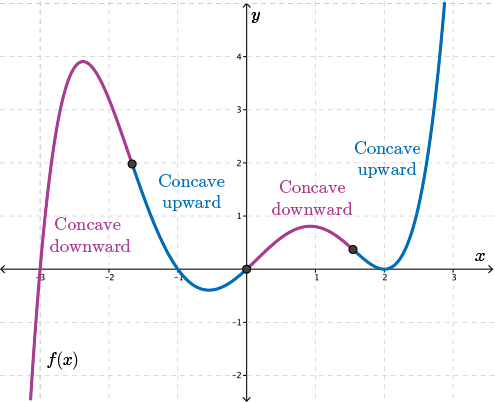

Polynomial functions can have multiple intervals of different concavity.

Consider the following fifth degree polynomial function.

This polynomial is concave upward within two intervals and concave downward within two intervals. And these intervals are separated by three points of inflection.

I now recommend that you try the investigation attached to this module. And then we will continue our discussion on points of inflection in concavity.

Investigation

See the investigation in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 3

Points of Inflection and Concavity

So now that you are familiar with identifying intervals of concavity and identifying possible points of inflection, let's make some definitions.

A point, \((c,f(c))\), is a point of inflection if \(f\) is continuous at \(x=c\) and \(f''(x)\) changes sign at \(x=c\).

From our investigation, we see that points of inflection may be points where \(f''(x)=0\) or \(f''(x)\) does not exist. But of course, in order for these points to be points of inflection, we must make sure that \(f''(x)\) changes sign at that value of \(x\).

Points of inflection may also be critical points where \(f'(x)\) does not exist.

The big idea here is that points of inflection separate intervals where the curve is concave upward from intervals where the curve is concave downward, or vice versa.

Test for Concavity

We now need a test for concavity. This test allows us to algebraically find the intervals of concavity for a function.

If a function, \(f\), is twice differentiable (meaning that we can find the first derivative and second derivative) on an interval, \(I\), then

- the graph of \(f\) is concave upward on \(I\) if \(f''(x)\gt 0\) for all \(x\) in \(I\), and

- the graph of \(f\) is concave downward on \(I\) if \(f''(x)\lt 0\) for all \(x\) in \(I\).

Let's now use this test for concavity to answer the following example.

Examples

Example 4

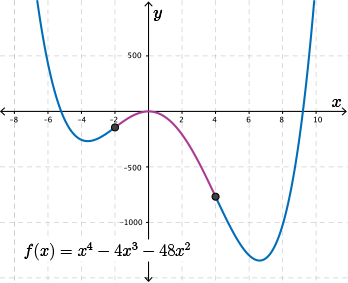

Without the aid of graphing technology, find where the function \(f(x)=x^4-4x^3-48x^2\) is concave upward and where it is concave downward.

Solution

Since \(f(x)\) is differentiable to any order throughout its domain, as this is a polynomial function, only points of inflection where \(f''(x)=0\) will separate the intervals of concavity.

So, we begin by finding all values of \(x\) that have \(f''(x)=0\).

Differentiating \(f(x)\), we have

\[f'(x)=4x^3-12x^2-96x\]

To find the points of inflection, we need to differentiate \(f'(x)\) to obtain \(f''(x)\), and then set \(f''(x)=0\) and solve for \(x\).

\[ \begin{align*}f''(x)&=12x^2-24x-96 \\ 0&=12(x^2-2x-8)\\ 0&=12(x-4)(x+2)& \text{factoring} \end{align*}\]

Thus, possible points of inflection occur at \(x=4\) and \(x=-2\). Rearranging the points of inflection from least to greatest gives us three possible intervals of concavity: \(x\lt -2\), \(-2\lt x\lt 4\), and \(x\gt 4\). These intervals will be the column headings in our summary table.

To determine whether \(f(x)\) is concave upward or downward in each of these three intervals, we test whether \(f''(x)=12(x-4)(x+2)\) is positive or negative within each interval.

Starting with the first interval, which is when \(x\lt -2\), let's choose a value of \(x\) in this interval, say \(-3\). If we were to substitute \(-3\) into the expression for \(f''(x)\), we would have

\[f''(-3)=(+)(-)(-)=+\]

So we know that \(f''(x)\gt 0\) in this interval. Since \(f''(x)\gt 0\), we know that the graph is concave upwards.

Let's now pick a value of \(x\) in the second interval. Here, \(-2\lt x\lt 4\). Let's choose the value \(x\) as \(0\). If we were to substitute \(0\) into the second derivative function, we would see that

\[f''(0)=(+)(-)(+)=-\]

So \(f''(x)\lt 0\) in this interval, which means that the graph of \(f(x)\) is concave downward.

Finally, in the third interval, \(x\gt 4\). So let's choose \(x\) to be \(5\) and determine if \(f''(5)\) is positive or negative. Substituting \(x = 5\) into the second derivative function, we see that

\[f''(5)=(+)(+)(+)=+\]

Therefore, \(f''(x)\gt 0\), which tells us that the graph is concave upwards.

Summarizing the required information for \(f(x)=x^4-4x^3-48x^2\) in a table, we get the following:

| |

\(x\lt -2\) |

\(-2\lt x\lt 4\) |

\(x\gt 4\) |

| \(f''(x)\) |

\(f''(x)\gt 0\) |

\(f''(x)\lt 0\) |

\(f''(x)\gt 0\) |

| \(f(x)\) |

concave upward |

concave downward |

concave upward |

Let's check our work by graphing this function with graphing technology.

We see that our answer was correct.

Lesson Part 4

The Second Derivative

In Summary

To algebraically determine a function's intervals of concavity, we first need to determine the possible points of inflection by finding the values of \(x\) where \(f''(x)=0\), and where \(f'\) or \(f''\) do not exist.

These points will tell us the possible boundaries of each interval of concavity.

Then, we test points inside these intervals to determine whether \(f''(x)\) is positive or negative on each interval.

This leads us to the second derivative test.

The Second Derivative Test

If the second derivative \(f''(x)\) of the function \(f(x)\) is continuous on an open interval that contains \(x=c\) and \(f'(c)=0\), then

- if \(f''(c)\gt 0\) (i.e., \(f(x)\) is concave upward at \(x=c\)), then \(f(x)\) has a local minimum at \(c\), and

- if \(f''(c)\lt 0\) (i.e., \(f(x)\) is concave downward at \(x=c\)), then \(f(x)\) has a local maximum at \(c\).

Note:

It is important to make this special note.

The second derivative test does not address the case where \(f''(x)=0\). If \(f''(c)=0\), then a maximum value, a minimum value, or neither may exist at \(c\).

This test also fails if \(f''(x)\) does not exist.

Luckily, we can use the first derivative test to draw conclusions about the graph of \(f(x)\) in these cases.

Lesson Part 5

Examples

Now try the following example.

Example 5

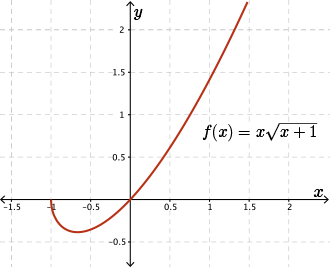

Find any intervals of concavity for the function \( f(x) = x\sqrt{x+1}\).

Solution

Before we find the intervals of concavity, we must first start by checking the domain of \(f(x)\) and then determine any points where \(f(x)\) is not differentiable; in other words, this tells us where \(f''(x)\) does not exist.

Since \(\sqrt{x+1}\) has real answers only when \(x+1 \geq 0\), the function's domain is restricted to \(x\geq- 1\).

Let's now differentiate \(f(x)\) twice, to find possible points of inflection.

First, we express this function with a rational exponent rather than as a radical, which gives \( f(x) = x(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}\).

Then, we differentiate.

\(\begin{align*} f'(x)&= (1)(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}+x\left[\dfrac{1}{2}(x+1)^{-\frac{1}{2}}(1)\right] & \text{by product, power, and chain rules} \\ & = (x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}+\dfrac{x}{2(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}}\\ & = \dfrac{2(x+1)+x}{2(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}} & \text{common denominator}\\ & = \dfrac{3x+2}{2(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}} \quad \text{for } x\gt -1 \end{align*}\)

Remember to state the restriction. The original domain of \(f(x)\) was for \(x\geq- 1\). However in this case, when \(x = -1\), we would have division by \(0\). So the first derivative function is only defined for \(x\gt -1\).

Differentiating \(f'(x)\) will give \(f''(x)\).

First, let's write this expression as a product of factors with rational exponents: \(f'(x)\) could be written as \(f'(x)= \dfrac{1}{2}(3x+2)(x+1)^{-\frac{1}{2}}\).

Again, we will use the product rule to differentiate this expression. And then we will also need to use the chain rule.

Since \(f'(x)\) has a constant multiple of \(\frac{1}{2}\), so does \(f''(x)\). So in \(f''(x)\), we're going to have a factor of \(\frac{1}{2}\) out in front. Differentiating the product of the two binomial expressions, we have

\(\begin{align*} f''(x) &= \dfrac{1}{2}\left[(3)(x+1)^{-\frac{1}{2}}+(3x+2)\left(-\dfrac{1}{2}(x+1)^{-\frac{3}{2}}(1)\right)\right] & \text{chain rule}\\ &= \dfrac{1}{2}\left[\dfrac{3}{(x+1)^{\frac{1}{2}}}-\dfrac{3x+2}{2(x+1)^{\frac{3}{2}}}\right] \\ &= \dfrac{6(x+1)-(3x+2)}{4(x+1)^{\frac{3}{2}}} & \text{common denominator}\\ &= \dfrac{3x+4}{4(x+1)^{\frac{3}{2}}} \quad \text{for }x\gt -1 & \text{collect like terms}\end{align*}\)

Again, let's examine this function and make sure we state restrictions. Ultimately we do have \(\sqrt{x+1}\), since \(x + 1\) is raised to the exponent \(\frac{3}{2}\). So we know that this function is defined for all values of \(x\geq- 1\). However, since this expression is in the denominator, we also know that \(x \neq -1\) since this would lead to division by \(0\). So this function is restricted to values of \(x\gt -1\).

Notice that \(f''(x)\) is defined for all \(x\) in the domain of \(f(x)\).

Since points of inflection to this curve may occur when \(f''(x)=0\), solve for \(x\) in the equation

\(\begin{align*} 0 &= \dfrac{3x+4}{(x+1)^{\frac{3}{2}}} && \implies && x=-\dfrac{4}{3}\end{align*}\)

But let's keep in mind the domain of \(f''(x)\). Recall that \(f'(x)\) and \(f''(x)\) are not defined for \(x\leq-1\).

Since \(-\dfrac{4}{3}\lt -1\) and \(f''(x)\) is only defined for values of \(x \gt -1\), this function's graph has no points of inflection. So we only need to consider one interval of \(x\): That is where \(x \gt -1\).

Since \(x\gt -1\) implies that \(f''(x)\gt 0\) for all \(x\) in the function's domain, this function is concave upward for \(x\gt -1\).

Let's verify our answer by examining the graph of \( f(x) = x\sqrt{x+1} \).

We see that our conclusion was correct.

It is worth noting that as we travel towards \(x = -1\) along the graph from the right side, the tangent line begins to approach a vertical tangent as \(x\) approaches \(-1\) from the right side. In other words, as \(f'(x) \rightarrow -\infty\) as \(x\rightarrow-1^+\), the tangent line becomes vertical as \(x\rightarrow-1^+\).

This observation connects well with our conclusion that \(f(x)\) is not differentiable for \(x = -1\).

Lesson Part 6

Examples

Let's finish this module with another example. This one is a bit more challenging.

Challenge Problem

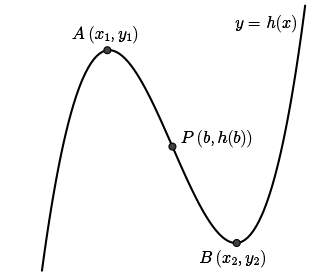

Suppose that the cubic polynomial \(h(x)=x^3-3bx^2+3cx+d\) has a local maximum at \(A\,(x_1,y_1)\) and a local minimum at \(B\,(x_2,y_2)\). Prove that the point of inflection of \(h(x)\) is at the midpoint of the line segment \(AB\).

McGee, I. J., Nicholls, G. T., Ponzo, P. J. et al. (1988). Calculus. Toronto, ON: Holt, Rinehart and Winston of Canada Limited.

Solution

First, since \(h(x)\) is a cubic polynomial having a local maximum and a local minimum, it must have exactly one point of inflection.

Why is this? A cubic of this shape must be concave upward for the section of the curve containing the local minimum and then concave downward for the section containing the local maximum.

The curve must change concavity somewhere in between those two points (local extremes) and since the curve is continuous, this must happen at a point of inflection. You can also argue that this must be the only point of inflection.

As the question asks us, we need to locate this point of inflection and determine its position relative to the local extremes (occurring at the critical points).

To determine the position of the critical points of the curve \(y=h(x)=x^3-3bx^2+3cx+d\), let's begin by differentiating \(h(x)\) and solving the equation \(h'(x)=0\).

\[h'(x)=3x^2-6bx+3c\]

We know \(h'(x)\) is defined everywhere, and so the critical points will occur where \(h'(x)=0\), so we need to solve the equation \(h'(x)=0\).

\[0=3x^2-6bx+3c\]

Factoring and using the quadratic formula, we have

\[0=3(x^2-2bx+c) \quad \implies \quad x=\dfrac{2b\pm \sqrt{4b^2-4c}}{2} \quad \implies \quad x=b\pm \sqrt{b^2-c}\]

Therefore, the critical points of \(h(x)\) occur at \(x=b+ \sqrt{b^2-c}\) and \(x=b- \sqrt{b^2-c}\) .

To determine the position of the point of inflection of the curve \(y=h(x)\), we must first determine \(h''(x)\) by differentiating \(h'(x)=3x^2-6bx+3c\), giving

\[h''(x)=6x-6b\]

To determine the position of the point of inflection, we solve the equation \(h''(x)=0\).

\(\begin{align*} 0 &=6(x-b) \\ x &=b \end{align*}\)

Therefore, a point of inflection occurs at \(x=b\).

Let's now make a quick sketch of \(h(x)=x^3-3bx^2+3cx+d\). Recall that at \(A\,(x_1,y_1)\) we have a local maximum, and at \(B\,(x_2,y_2)\) we have a local minimum. We know that the point of inflection is going to happen between this local maximum and local minimum, so let's put that point on the sketch.

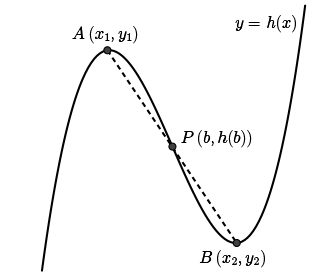

Now, the point of inflection, \(P\,(b,h(b))\), occurs when \(x = b\).

Look at the \(x\) values that we found for the critical points. The critical points at \(x=b+ \sqrt{b^2-c}\) and \(x=b- \sqrt{b^2-c}\) are horizontally equidistant from the point of inflection at \(x=b\).

Thus, \(x=b\) is the \(x\)-value of the midpoint of line segment \(AB\); i.e., \(\dfrac{x_1+x_2}{2}=b\)

Now, we need to check if the point of inflection has the same \(y\) value of the midpoint between the local maximum and local minimum. To determine whether \(\dfrac{y_1+y_2}{2}=h(b)\), we must show that both sides of this equation are the same.

Let \(\sqrt{b^2-c}=k\) for convenience, so that \(x_1=b-k\) and \(x_2=b+k\) (assuming \(x_1\lt x_2\)). Thus, the left side of the equation is

\(\begin{align*} &\dfrac{1}{2}(y_1+y_2) \\ &=\dfrac{1}{2}[h(b-k)+h(b+k)] \\ &=\dfrac{1}{2}[(b-k)^3-3b(b-k)^2+3c(b-k)+d+(b+k)^3-3b(b+k)^2+3c(b+k)+d] \\ &=\dfrac{1}{2}[2b^3+6bk^2-6b^3-6bk^2+6cd+2d] \\ &=-2b^3+3cd+d \end{align*}\)

The right side of the equation is

\(\begin{align*} h(b) &=b^3-(3b)( b^2)+3cb+d \\ & =-2b^3+3cb+d \end{align*}\)

This is equal to the left-hand side found previously.

So we have now proven that the point of inflection does, indeed, lie at the midpoint of the line segment between the local maximum and the local minimum.

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.