Lesson Part 1

In This Module

- We revisit one of the most important applications of differential calculus: optimization.

- The problems we consider will involve exponential and trigonometric modelling functions.

Examples

In the first example, we will consider a profit function that involves an exponential and attempt to maximize this function.

Example 1

The net monthly profit, in dollars, from the sale of a certain item is given by the formula \(P(x) = 60x^{2}e^{-0.25x}+40 \), where \(x \geq 1\) is the number of items sold, in hundreds.

Note: If we evaluate \(P(1)\), we will get the net monthly profit in dollars, assuming the company sells \(100\) items. Similarly, if we evaluate \(P(x)\) at \(x=2\), we will get the monthly profit in dollars, if the company sells \(200\) items, and so on.

Part A. If the factory can produce up to \(1000\) items per month, determine the number of items that yield the maximum profit. What is this maximum profit?

Solution

First, since \(x\) is measured in hundreds of items, \(x=10\) corresponds to \(10\times 100 = 1000\) units of the item, we need to determine the maximum value of the profit function \(P(x)\) for \(1 \leq x \leq 10\).

Now, \(P(x)\) involves a product of a polynomial and an exponential and then some constants.

Since \(P(x)\) is continuous over all of \(\mathbb{R}\), it is continuous over the interval \([1,10]\).

By the extreme value theorem, \(P(x)\) must attain a maximum value on the interval \([1,10]\).

Let's locate the critical points of \(P(x)\) over this interval.

\(P(x)\) is the sum of two terms. The first term is a product of functions.

So, using the product rule and the chain rule, we differentiate \(P(x)\):

\[ \begin{align*} P'(x)&=60 \left[ x^{2} \dfrac{d}{dx}\left(e^{-0.25x}\right) +e^{-0.25x} \dfrac{d}{dx}(x^2)\right] \\ &=60 \left[ x^{2} (-0.25)\left(e^{-0.25x}\right) +e^{-0.25x} (2x)\right] \\ &=-15 x^{2} e^{-0.25x} + 120 xe^{-0.25x} \end{align*} \]

Since the derivative is defined for all \(x\), the critical points will occur exactly when the derivative is \(0\).

We have

\[ \begin{align} P'(x)&=0 \\ -15 x^{2} e^{-0.25x} + 120 xe^{-0.25x}&=0 \\ - x^{2} e^{-0.25x} + 8 xe^{-0.25x} &=0 \\ e^{-0.25x}x(8-x) &=0 \end{align} \]

We obtain \((1)\) and \((2)\) since \(P'(x)=-15 x^{2} e^{-0.25x} + 120 xe^{-0.25x}\). Since \(15\) and \(120\) are both divisible by \(15\), we divide \((2)\) by \(15\) to get \((3)\). Next we observe that we can factor out \(e^{-0.25x}\) from each term in the sum in \((3)\). Doing so, we are left with the factored expression \((4)\).

Since \(e^{-0.25x} \neq 0\) for all \(x\), we have \(P'(x) = 0\) if and only if \(x=0\) or \(x=8\).

Therefore, \(P(x)\) has two critical points, but only one, \(x=8\), lies in the interval \([1,10]\).

We evaluate the function at the critical point and the endpoints of the interval to locate the maximum value of \(P(x)\):

\[ \begin{align*} P(1)&=60 (1)^{2}e^{-0.25(1)} + 40 = 60e^{-0.25}+40 \approx 86.73 \\ P(8)&==60 (8)^{2}e^{-0.25(8)} + 40 = 3840e^{-2}+40 \approx 559.69 \\ P(10)&==60 (10)^{2}e^{-0.25(10)} + 40 = 6000e^{-2.5}+40 \approx 532.51 \\ \end{align*} \]

We observe that the function value at \(x=8\) is the largest.

Therefore, \(P(x)\) attains its maximum value at \(x=8\).

Now let's interpret this mathematical result in terms of the question at hand.

We conclude that the maximum profit attainable is \($559.69\), which is obtained by selling \(800\) items.

Part B. Repeat Part A assuming that the factory can produce only \(500\) items per month at full capacity.

Solution

Since \(x=5\) corresponds to \(500 \) items, we need to determine the maximum value of the profit function, \(P(x)\), for \(1 \leq x \leq 5\).

From Part A, we know that \(P(x)\) has no critical points on this interval—the only critical points were \(x=0\) and \(x=8\), which lie outside the interval.

So, the maximum value, guaranteed by the extreme value theorem, must occur at one of the endpoints.

We have \(P(1) = 86.73\) and \(P(5) \approx 469.76\) and so \(P(x)\) attains its maximal value at \(x=5\), corresponding to \(500\) items.

The maximum profit is \($469.76\).

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Example 2

A student's success in a course depends on how many hours the student studies.

Suppose that Jenny is studying for an exam and because of the nature of the course, the effectiveness of studying can be measured on a scale from \(0\) to \(10\) using the formula \(E(t) = 0.6(8+te^{-\frac{t}{15}})\) where \(t\) is the number of hours spent studying.

If Jenny has up to \(20\) hours for studying, how many hours should be spent to maximize effectiveness?

Source: Kirkpatrick, C., & Crippin, P. (2009). Calculus and Vectors (p. 241). Toronto, ON: Nelson Education.

Solution

So, we're probably all very aware that there is such a thing as not enough studying for an exam. But this question is exploring whether it's possible to study too much for an exam.

Jenny can spend anywhere from \(0\) to \(20\) hours studying for her exam, but we want to find the value that will maximize the effectiveness of her studying.

In terms of calculus, we need to determine the maximum value of the function \(E(t)\) on the interval \(0 \leq t \leq 20\).

First, we differentiate the function, with respect to time, in order to locate the critical points.

Using the product rule and the chain rule, we get \((5)\):

\[ \begin{align} E'(t)&= 0.6\left[ t \left(-\frac{1}{15}e^{-\frac{t}{15}}\right) + e^{-\frac{t}{15}}(1)\right] \\ &=-0.04te^{-\frac{t}{15}} + 0.6 e^{-\frac{t}{15}} \\ &=e^{-\frac{t}{15}}\left(0.6 - 0.04t\right) \end{align} \]

Expanding \((5)\), we get \((6)\). Notice that we can factor out \(e^{-\frac{t}{15}}\) in \((6)\) and we're left with \((7)\).

Since \(e^{-\frac{t}{15}} \neq 0\) for all \(t\), then \(E'(t) =0\) exactly when \(0.6 - 0.04t=0\), i.e., \(t = \frac{0.6}{0.04} = 15\), so \(E(t)\) has one critical point in the interval \([0,20]\).

We now evaluate the function at the critical point, \(t=15\), and the endpoints of the interval to locate the maximum value of \(E(t)\):

\[ \begin{align*} E(0)&=0.6(8+(0)e^{-\frac{0}{15}}) = 0.6(8) = 4.80 \\ E(15)&=0.6(8+15e^{-\frac{15}{15}}) = 0.6(8+15e^{-1}) \approx 8.11 \\ E(20)&=0.6(8+20e^{-\frac{20}{15}}) = 0.6(8+20e^{-\frac{4}{3}}) \approx 7.96 \end{align*} \]

Therefore, the maximum value occurs at \(t=15\).

To obtain the maximum effectiveness of \(8.11\), Jenny should study for \(15\) hours.

So apparently, in this case, we can study too much.

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Now let's move on to an example where the modeling function involves both an exponential and a trigonometric function.

Example 3

The vertical displacement of the body of a car after driving over a speed bump is modelled by the function \(h(t) = e^{-0.4t}\sin{(t)}\) where \(h\) is measured in meters and \(t\geq 0\) is measured in seconds.

At \(t=0\), just as the car is about to pass over the speed bump, we have \(h(0) = 0\), which corresponds to the resting height of the body of the car.

So, if at some time \(t\), \(h(t)\gt 0\), then the car's body is higher than its resting height at time \(t\), and if \(h(t)\lt 0\) then it is lower than its resting height.

Determine when the maximum vertical displacement occurs and find this maximum displacement.

Solution

This question involves some interpretation.

To find the maximum vertical displacement, we need to locate the times when the car's body is farthest from its resting height, either in the positive or the negative direction.

As we hit the speed bump, our car is going to go up and down, and we want to figure out the highest point and the lowest point that the car's body reaches.

Therefore, in terms of calculus, we need to find the absolute maximum and minimum values attained by the function \(h(t)\) over the interval \(t \geq 0\), and determine which value is largest in magnitude.

To do so, we first need to locate the critical points of the function \(h(t)\).

Using the product rule and the chain rule, we differentiate \(h(t)\) and find:

\[ \begin{align} h'(t)&= e^{-0.4 t}\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(\sin{(t)}\Big) + \sin{(t)} \dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(e^{-0.4t}\Big) \\ &=e^{-0.4t} \cos{(t)} + \sin{(t)} \left(-0.4e^{-0.4t}\right) \\ &=e^{-0.4t}\bigr(\cos{(t)} - 0.4 \sin{(t)}\bigr) \end{align} \]

The derivative of \(\sin{(t)}\) with respect to \(t\) is \(\cos{(t)}\). The derivative of the exponential, \(e^{-0.4t}\), using the chain rule is \(-0.4\left(e^{-0.4t}\right)\). So, we get \((9)\) from \((8)\). By factoring out the common factor \(e^{-0.4t}\) in \((9)\), we get \((10)\), which is in factored form.

Since \(h'(t)\) is defined for all \(t\), the only critical points occur when \(h'(t) = 0\). Since \(e^{-0.4t} \neq 0\) for all \(t\), we have \(h'(t) = 0\) exactly when

\[ \cos{(t)} - 0.4\sin{(t)}= 0 \]

Using this equation, we can get a value for \(\tan{(t)}\).

In particular, we find, after rearranging and dividing through by \(\cos{(t)}\), that the \(\tan{(t)}=2.5\):

\[ \begin{align*} \cos{(t)}&=0.4 \sin{(t)} \\ \dfrac{\sin{(t)}}{\cos{(t)}}&= \dfrac{1}{0.4} \\ \tan{(t)}&=2.5 \end{align*} \]

Therefore, \(t = \tan^{-1}{(2.5)} \approx 1.19\), and since \(\tan{(t)}\) has period \(\pi\), we have \(h'(t)=0\) when \(t \approx 1.19 + k\pi\) for any integer \(k\).

Therefore, the function \(h(t)\) has infinitely many critical points, each corresponding to a local extreme.

So, let's plot some of these points and draw a rough sketch of the function to figure out what's going on physically.

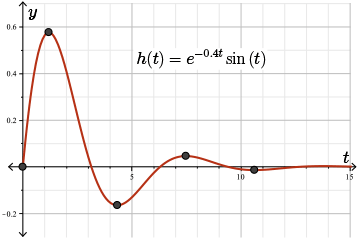

Plotting the function values at a few of the critical points (and using the algorithm from a previous module), we can make the following sketch of \(h(t)\):

| \(t\approx\) |

\(1.19\) |

\(4.33\) |

\(7.47\) |

\(10.61\) |

| \( h(t) \approx\) |

\(0.58\) |

\(-0.16\) |

\(0.05\) |

\(-0.01\) |

Since the function \(h(t)\) involves \(\sin{(t)}\), the curve oscillates about the \(t\)-axis as we would expect.

As the term \(\sin{(t)}\) is multiplied by the decreasing function \(e^{-0.4t}\), we see that the amplitude of the oscillations decreases as \(t\) increases.

This matches what we would expect in a physical scenario.

When we go over the bump, we expect the highest displacement to be at the very beginning.

Then, the car eventually settles down as time goes on.

Therefore, the critical point \(t \approx 1.19\) corresponds to the absolute maximum of the function \(h(t)\) and the critical point \(t \approx 4.33\) corresponds to the absolute minimum.

Clearly, the maximum displacement occurs in the positive direction at \(t \approx 1.19\).

Therefore, the maximum displacement occurs approximately \(1.19\) seconds after the car hits the bump, and the maximum displacement is \(h(1.19)\), which is approximately \(0. 58\) m in the upwards direction.

What is the physical meaning of the absolute minimum value of \(h(4.33) \approx -0.16\) m?

Recall that \(h=0\) corresponds to the resting height of the car's body, not a height of \(0\) as measured from the ground—the car, of course, is sitting some distance above the ground.

Since the body of the car moves \(-0.16\) m downward, if the bottom of the car's body rests less than \(0.16\) m above the ground, then this speed bump will cause the body of the car to crash into the ground.

So, car manufacturers can use this analysis to ensure that the cars they build can handle a reasonable speed bump without crashing into the ground.

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 4

A company makes troughs for holding water for farm animals.

The frame of the trough is made by taking a piece of sheet metal and folding \(\frac{1}{3}\) of the sheet up on each side, so that each side makes an angle \(\theta\) with the ground.

Here we see a picture of the trough.

Since the sheet metal is divided into three equal parts, we will denote the length of these equal parts by \(x\).

Assuming that the original piece of sheet metal is \(45\) cm wide, determine the angle \(\theta\) that maximizes the volume of water that the trough can hold.

What is the cross-sectional area of this maximal trough?

Solution

First, we note that we only have a proper trough if \(0 \lt \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\). Why?

If \(\theta\gt\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) or \(90\) degrees, then we wouldn't get a proper trough shape because the sides would be angled in.

If \(\theta=0\), then the sides are actually lying on the ground, which would mean, again, we don't get a real trough and all the water would fall out.

We need to keep this physical restriction in mind while we are solving the problem using calculus.

So, let's first think about what we might expect a maximal value to be.

If \(\theta\) is really close to \(0\), then we would have a wide but short trough.

On the other hand, if \(\theta\) is close to \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\) or \(90\) degrees, then we have a very tall but thin trough.

So, we would expect the maximal value to be some compromise between the width and the height of the trough.

To maximize the volume of water in the trough, we need to maximize the trapezoidal cross-sectional area of the trough.

The area of the trapezoid can be divided into the area of a rectangle in the middle and the areas of \(2\) congruent right-angled triangles on the left and on the right, as shown in the figure.

We denote the base and height of these two triangles by \(\textcolor{Mulberry}{b}\) and \(\textcolor{NavyBlue}{h}\) respectively.

Using geometry, we know that the angle between the base \(\textcolor{Mulberry}{b}\) and the hypotenuse \(\textcolor{BrickRed}{x}\) must also be equal to \(\theta\).

In terms of the variables in the question, the area of the cross-section is equal to

\[ \begin{align*} A &= 2 \times \text{area of the triangle} + \text{area of the rectangle} \\ &= 2\left(\frac{1}{2}bh\right) + xh \\ &= bh + xh \end{align*} \]

Since we are asked to find \(\theta\) that maximizes the area, we need an expression for the cross-sectional area in terms of only the variable \(\theta\).

We can use trigonometry to do so. Let's look at one of the congruent triangles on either side of the trapezoid, which has adjacent \(\textcolor{Mulberry}{b}\), opposite \(\textcolor{NavyBlue}{h}\), and hypotenuse \(\textcolor{BrickRed}{x}\). Since sine is the opposite side over the hypotenuse, \(\sin{\left(\theta\right)}=\dfrac{h}{x}\). This implies

\[ h = x \sin{(\theta)}\]

Similarly, cosine is the adjacent side over the hypotenuse, \( \cos{\left(\theta\right)}=\dfrac{b}{x}\). This implies

\[ b = x \cos{(\theta)} \]

Substituting these expressions into the equation for the area, we get

\[ \begin{align*} A&= bh + xh \\ &=\Bigr(x \cos{(\theta)}\Bigr)\Bigr(x \sin{(\theta)}\Bigr) + x \Bigr(x\sin{(\theta)}\Bigr) \\ &= x^{2} \cos{(\theta)}\sin{(\theta)} + x^{2} \sin{(\theta)} \end{align*} \]

Since we are given that the sheet metal has width \(45\) cm, we have \(x = \dfrac{1}{3}(45) = 15\) cm and so the area, as a function of \(\theta\) only, is equal to

\[ \begin{align*} A(\theta)&=15^{2}\cos{(\theta)}\sin{(\theta)} + 15^{2}\sin{(\theta)} \\ &=225\left(\cos{(\theta)}\sin{(\theta)} +\sin{(\theta)}\right) \end{align*} \]

We will determine the absolute maximum value of the function \(A(\theta)\), over the closed interval \(\left[0,\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right]\), using the extreme value theorem. First, let's locate the critical points of the area function.

Using the product rule and simplifying,

\[ \begin{align*} A'(\theta) & =225 \left[\cos{(\theta)} \dfrac{d}{d\theta}\Big(\sin{(\theta)}\Big) +\sin{(\theta)}\dfrac{d}{d\theta}\Big(\cos{(\theta)}\Big)+\cos{(\theta)} \right] \\ & =225 \Big[\cos{(\theta)}\cos{(\theta)} + \sin{(\theta)}(-\sin{(\theta)})+\cos{(\theta)} \Big] \\ & =225 \Big[\cos^{2}{(\theta)}-\sin^{2}{(\theta)}+\cos{(\theta)} \Big] \end{align*} \]

Therefore, \(A'(\theta) = 0\) if and only if \(\cos^{2}{(\theta)}-\sin^{2}{(\theta)}+\cos{(\theta)} =0\).

To find the critical point(s), we need to solve this equation.

First, let's rewrite this equation in terms of either just sine or cosine. Let's do cosine.

We rewrite the expression \(\cos^{2}{(\theta)}-\sin^{2}{(\theta)}+\cos{(\theta)}\) in terms of only \(\cos{(\theta)}\) as follows:

\[ \begin{align*} \cos^{2}{(\theta)}-{\color{BrickRed}\sin^{2}{(\theta)}}+\cos{(\theta)}&=\cos^{2}{(\theta)}-{\color{BrickRed}(1-\cos^{2}{(\theta)})} +\cos{(\theta)} \\ &=2 \cos^{2}{(\theta)} + \cos{(\theta)} - 1 \end{align*} \]

Now, we need to find the roots of this equation. How do we do so?

This is a quadratic polynomial in \(\cos{(\theta)}\), that is, if we let \(u= \cos{(\theta)}\) then we have

\[2 \cos^{2}{(\theta)} + \cos{(\theta)} - 1=2u^{2} + u -1\]

We can factor the polynomial \(y = 2u^{2} +u -1 = (2u-1)(u+1)\), so we can factor the trigonometric expression as

\[2 \cos^{2}{(\theta)} + \cos{(\theta)} - 1 = (2 \underbrace{\cos{(\theta)}}_{u} -1)(\underbrace{\cos{(\theta)}}_{u}+1)\]

using the same formula from above.

Now, we can find the roots.

\[(2\cos{(\theta)} -1)(\cos{(\theta)}+1)=0\]

This expression is \(0\) if and only if one of the factors is \(0\).

Therefore, \(A'(\theta) = 0\) if and only if \(\cos{(\theta)} = \frac{1}{2}\) or \(\cos{(\theta)} = -1\).

Remember that we're restricting ourselves to the interval from \(0\) to \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

There is no angle \(\theta\) between \(0\) and \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) that satisfies \(\cos{(\theta)} = -1\), but there is one such angle that satisfies \(\cos(\theta) = \dfrac{1}{2}\), namely \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\).

So, there is exactly one critical point in the interval \(\left[0,\frac{\pi}{2}\right]\): \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{3}\).

Next, we evaluate the function at the critical point and the endpoints to locate the maximum value:

\[ \begin{align*}A(0) & = 225 \Bigr(\cos{(0)}\sin{(0)} +\sin{(0)}\Bigr) = 225(1\cdot0 + 0) = 0 \\ A\left(\tfrac{\pi}{3}\right) & =225 \left(\cos\left(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right)\sin\left(\tfrac{\pi}{3}\right) +\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right)\right) = 225\left(\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) + \dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) \approx 292 \\ A\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right) & =225 \left(\cos\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right) +\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\right) = 225(0 \cdot 1 + 1) = 225 \end{align*} \]

Note:

We have \(A(0) = 0\) and this is the absolute minimum value over the interval \(\left[0,\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right]\).

This makes sense physically: an angle of \(\theta = 0\) corresponds to the sides of the trough lying flat on the ground and so the cross-sectional area should be \(0\) in this case.

Comparing the function values, we have that \(A(\theta)\) achieves its maximum value at \(x = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\).

Therefore, the maximum cross-sectional area, and hence the maximum volume, occurs when \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\), and the maximum possible cross-sectional area is approximately \(292\) cm\(^{2}\).

Lesson Part 5

Examples

Now let's move on to the challenge problem for this module.

Challenge Problem

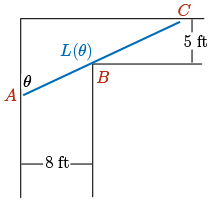

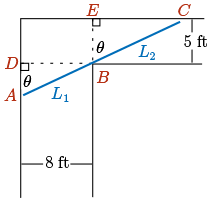

A pipe is to be carried down a hallway that is \(8\) ft wide. At the end of the hallway, there is a right-angled right turn into a narrower hallway that is only \(5\) ft wide.

If the pipe needs to remain horizontal while carried, then what is the length of the longest pipe that can be carried around the corner?

Solution

Now this problem can be solved using our usual technique for finding extreme values of functions, but the function to choose here is not at all obvious.

So, to build up this function, here are some important observations about the physical situation:

-

An optimal way to pass the pipe through the hallway is to slide it along the left wall of the first hallway, and turn it around the corner while the two endpoints of the pipe remain touching the walls, until it is parallel to the walls of the second hallway.

Try to convince yourself that any pipe that can make the turn can make the turn if turned in this manner.

We might as well think about this as our physical situation.

So, we will think about keeping the bottom endpoint of the pipe in contact with the left wall of the first hallway for the entire turn.

We will call the angle that the pipe makes with this left wall \(\theta\).

-

If the pipe manages to make the turn, then the angle \(\theta\) (defined in part 1)) must pass from \(\theta=0\) to \(\theta= \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), taking on every angle in between.

So have a look at the following picture.

\(\theta=0\) will correspond to the very beginning once we've slid our pole all the way down that first wall so the front is touching the corner.

Assuming that we have as long of a hallway as we'd like, a pipe of any length can fit at this angle.

Now, we start to move the front end of the pipe along the back wall.

In doing so, we're changing the angles that the pipe is making with that left hand wall.

\(\theta\) is going to continuously increase from \(0\) until it finishes the turn, and at the end, we have \(\theta=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

In other words, the pipe is perpendicular to that original left hand wall.

-

As we've noted, assuming that our hallways are arbitrarily large, any pipe can fit at angle \(\theta=1\) and \(\theta=\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

But there are built restrictions for all other theta in between these two values.

More precisely, for each angle \(\theta\) in the interval \(\left(0, \dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\), there is a maximum length, \(L(\theta)\), of a pipe that can fit in the hallway while making an angle of \(\theta\) with the left wall.

Let's try and get a handle of what this means with a picture.

This maximum length is the length of the pipe that has the following configuration: tangent to the left wall at \(A\), the inner corner at \(B\), and the upper wall at \(C\).

To convince ourselves that this fact is true, we can think about drawing in various pipes making an angle \(\theta\) with that left wall, and it should be clear that the longest pipe that can fit in this configuration is this length \(l\) theta that we've shown in the picture.

Now of course, this maximal length depends on \(\theta\).

Different values of \(\theta\) will have different maximal lengths.

-

For a pipe to make the turn, it must fit at every point during the turn.

If it cannot turn, then at some point, it gets stuck at some angle \(\theta\).

So, why would it get stuck? Well, this must mean that the length of the pipe is bigger than the maximum length that fits at that angle \(\theta\).

In other words, the length must be larger than the maximum allowable pole for that angle \(\theta\).

We can formulate this as follows.

For a pipe of length \(\mathcal{L}\) to make the turn, we must have \(\mathcal{L} \leq L(\theta)\) for all \(0 \lt \theta \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2}\).

If the function \(L(\theta)\) has an absolute minimum value, say \(L_{0}\), over the interval \(\left(0, \dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\), then any pipe that can make the turn must have length \(\mathcal{L} \leq L_{0}\).

It follows that the longest pipe that can make the turn is a pipe whose length is equal to this minimum length \(L_{0}\).

This might sound a little bit strange, but from our four observations, this is true.

The maximum length of the pipe that can fit is equal to the minimum value of the function \(L\left(\theta\right)\).

Now, we will attempt to determine the value of \(L_{0}\)—the absolute minimum of the function \(L(\theta)\) over \(\left(0, \dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\).

First, we can obtain an expression for \(L(\theta) = L_{1} + L_{2}\) using the above diagram, which is shown here again.

Here we're splitting up the pole into two lengths \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\), as depicted.

Let's draw in a few more reference points to help us.

We want to find \(L\left(\theta\right)\), which is, of course, \(L_{1}\) plus \(L_{2}\).

What is known in this diagram? \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\) are unknown, but we do know the widths of the two hallways.

In terms of our notation, we know that \(DB=8\) and \(EB=5\).

Now we can use trigonometry to get an expression for \(L_{1}\) and \(L_{2}\).

Using the left hand triangle, we can find an expression for \(L_{1}\).

\[\sin{(\theta)} = \dfrac{DB}{AB} =\dfrac{8}{L_{1}} \Longrightarrow L_{1} = 8 \csc{(\theta)}\]

Similarly, if we look at the right hand triangle, using basic geometry, we know that the angle \(EBC\) has to also be equal \(\theta\), and so

\[\cos{(\theta)}= \dfrac{EB}{BC} =\dfrac{5}{L_{2}} \Longrightarrow L_{2} = 5 \sec{(\theta)}\]\[L(\theta) = L_{1} + L_{2} = 8 \csc{(\theta)} + 5 \sec{(\theta)}\]

So, what does this function give? For each \(\theta\) between \(0\) and \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\), \(L\left(\theta\right)\) is giving us the length of the longest pole that can fit in our hallway while making an angle \(\theta\) with the left hand wall.

We need to find the minimum value of \(L(\theta)\).

The rest of the problem should be pretty straightforward.

Differentiating gives

\[ \begin{align*} L'(\theta)&=8\Big(-\csc(\theta)\cot(\theta)\Big) +5\sec(\theta)\tan(\theta) \\ &=5\sec(\theta)\tan(\theta)-8\csc(\theta)\cot(\theta) \end{align*} \]

as \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(\csc(\theta)\Big) = -\csc(\theta)\cot(\theta)\) and \(\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(sec(\theta)\Big ) = \sec(\theta)\tan(\theta)\).

Setting \(L'(\theta) = 0\), gives

\[5 \sec{(\theta)}\tan{(\theta)} -8\csc{(\theta)}\cot{(\theta)}=0 \]

Now we solve this equation:

\[ \begin{align*} 5 \sec{(\theta)}\tan{(\theta)} & =8\csc{(\theta)}\cot{(\theta)} \phantom{\sqrt{\frac{8}{5}}} \\ \dfrac{\sec{(\theta)}\tan{(\theta)}}{\csc{(\theta)}\cot{(\theta)} } & =\frac{8}{5} \phantom{\sqrt{\frac{8}{5}}} \\ \dfrac{\sin{(\theta)} \tan{(\theta)}}{\cos{(\theta)} \cot{(\theta)}} & =\frac{8}{5} \phantom{\sqrt{\dfrac{\sqrt{8}}{\sqrt{5}}}} \\ \tan^{3}{(\theta)} & =\frac{8}{5} \\ \tan{(\theta)} & =\sqrt[3]{\frac{8}{5}} \end{align*} \]

Since we are working over the interval \(0\lt \theta \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), we have \(\theta =\tan^{-1}{\left( \sqrt[3]{\dfrac{8}{5}} \right)} \approx 0.863413605\).

Let's denote this angle by \(\theta_{0}\).

We can check using either the first derivative or second derivative test that \(L(\theta_{0})\) is a local minimum of the function \(L(\theta)\), and that it is the absolute minimum over the interval \(0 \lt \theta \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2}\). (You should verify this by examining the sign of \(L'(\theta)\) over this open interval).

Therefore, \(L_{0} = L(\theta_{0})\).

Using our calculator, we find \(L(\theta_{0}) \approx L(0.863413605) \approx 18.21953370\) and so the longest pipe that can make the turn measures approximately \(18.2\) feet.

Finally, we include a graph of the function \(L(\theta)=8\csc(\theta)+5\sec(\theta)\) for our reference.

The curve \(L(\theta)\) has one minimum in the interval \(\left(0,\dfrac{\pi}{2}\right)\), located at approximately \(\theta=0.86\), and has vertical asymptotes at \(x=0\) and \(\dfrac{\pi}{2}\).