Lesson Part 1

In This Module

- We will revisit the topic of related rates using modelling functions that involve exponential, logarithmic, and trigonometric functions.

Strategy for Solving Related Rates Problems

Let's recall our general strategy for solving related rates problems:

- Determine the related quantities in the question and identify the principal formula relating them. Can you draw a diagram of the physical situation to help?

- What are you given?

- What are you asked to find?

- If there are more than two quantities, then it may be necessary to express one of the variables in terms of another and then substitute back into the primary equation, thus eliminating one quantity.

- Differentiate the principal equation with respect to time to find the formula relating the rates of change of our related quantities. NEVER substitute a value for a variable until AFTER you have differentiated!

Examples

Example 1—Part A

The amount of money that a company devotes to advertising has a direct impact on the profits generated by the sale of the company's product. Let \(x\) denote the annual advertising budget (in thousands of dollars) and let \(P\) denote the annual profit (in thousands of dollars) generated by the sale of the product. Due to the nature of the advertising, the annual profit, as a function of the annual advertising budget, is modelled by the following equation: \(P(x) = 100 - 15e^{-0.02x}\).

If the annual advertising budget is increasing at a constant rate of \($2,500\) per year, what is the rate of change of the annual profit when the advertising budget reaches \($60,000\)?

Solution

The two related quantities in this question are the annual advertising budget, \(x\), and the annual profit, \(P\).

Here, we are given the principal formula \(P(x) = 100 - 15e^{-0.02x}\).

What is given in this problem?

Given: We are given that the advertising budget is increasing at a constant rate of \($2,500\) per year. Since \(x\) is given in thousands of dollars, this translates to \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = 2.5\) thousand dollars per year.

Find: We are asked to find the rate of change of the annual profit at a particular moment in time. This translates to finding \(\dfrac{dP}{dt}\) when \(x=60\) thousand dollars.

Now, we differentiate the principal equation, implicitly, with respect to time.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dP}{dt} &= \dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(100 - 15e^{-0.02x}\Big) \\ &=- 15\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(e^{-0.02x}\Big) \\ &=-15(-0.02)\left (e^{-0.02x} \right ) \left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) & \text{chain rule}\\ &= 0.3 e^{-0.02x} \left ( \dfrac{dx}{dt} \right ) \end{align*}\]

Recall that \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = 2.5\).

We need to find the value of \(\dfrac{dP}{dt}\) when \(x = 60\), so we substitute these values to get

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dP}{dt} &= 0.3 e^{-0.02x} \left ( \dfrac{dx}{dt} \right ) \\ &= 0.3 e^{-0.02(60)} (2.5) \\ &=(0.75) e^{-1.2}\\ &\approx 0.225896 \end{align*}\]

Now remember that the profit is given in thousands of dollars, so this rate is given in thousands of dollars per year.

Therefore, multiplying by \(1,000\) and rounding to the nearest cent, the annual profit is increasing at a rate of \($225.90\) per year when the advertising budget is \($60,000\).

Example 1—Part B

The annual profit, as a function of the annual advertising budget, is modelled by the following equation: \(P(x) = 100 - 15e^{-0.02x}\).

Now let's suppose that our company is starting with a very large advertising budget but is making cutbacks.

If the annual advertising budget is decreasing at a constant rate of \($5,000\) per year, what is the rate of change of the annual profit when the annual advertising budget reaches \($100,000\)?

Solution

So here we're assuming the company starts with a budget much larger than \(100,000\) dollars, and it's slowly decreasing every year.

We can use the same related rates equation as in part a), but we substitute different values into the equation.

Given: \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = -5\) thousand dollars per year.

Find: \(\dfrac{dP}{dt}\) when \(x=100\) thousand dollars.

Substituting these values into the related rates equation, we get

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dP}{dt} & = 0.3 e^{-0.02x} \left ( \dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) \\ &= 0.3 e^{-0.02(100)} (-5) \\ &=(-1.5) e^{-2} \\ &\approx -0.203003 \end{align*}\]

Here, the negative sign means that the profit is decreasing. Again, multiplying by \(1,000\) and rounding to the nearest cent, we conclude that the annual profit is decreasing at a rate of \($203.00\) per year when the annual advertising budget is \($100,000\).

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Example 2—Part A

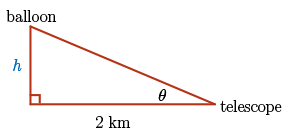

A hot air balloon rises straight up from the ground. An observer located \(2\) km away from the balloon's launching point is tracking the balloon through a telescope. Let \(\theta\) be the angle between the sight line of the telescope and the ground, measured in radians. Given that the balloon is rising at a constant rate of \(5\) km/h, calculate the following quantity:

At what rate is the angle \(\theta\) changing when \(\theta = \frac{\pi}{4}\)?

Solution

In this question, the \(2\) quantities that are changing with respect to time are the height of the hot air balloon, which we will denote by \(h\), and the angle between the sight line of the telescope and the ground, which is denoted by \(\theta\).

As the balloon rises, the value of \(h\) will increase, and so does the angle the telescope makes with the ground as the observer tracks the balloon.

We are told that the observer is \(2\) km away from the launch site.

We can make a diagram of the physical situation.

Of course, assuming that the balloon rises straight up, the trajectory of the balloon will be perpendicular to the ground. So we get a right angle triangle. Here, \(\theta\) is the angle between the ground and the sight line of the telescope, which is increasing as time goes on, and, of course, there's a \(2\) kilometer distance between the balloon's launching point and the telescope.

Given: In this question, we're given the balloon is rising at a rate of \(5\) kilometers per hour. This means that \(\dfrac{dh}{dt} = 5\) km/h.

Find: We are asked to find the rate of change of the angle \(\theta\). In particular, we're looking for \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\) when \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\).

We can use trigonometry to find the principal equation relating \(h\) and \(\theta\).

Relationship: In this right angle triangle, \(\tan(\theta)\) is given by the opposite side over the adjacent side. As \(\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{h}{2}\), we have \(h = 2 \tan(\theta)\).

Now, we differentiate this equation with respect to time. Remember that \(\theta\) is also changing with respect to time.

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dh}{dt} &= \dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(2 \tan(\theta)\Big) \\ &=\dfrac{d}{d\theta}\Big(2 \tan(\theta)\Big) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} \right ) & \text{chain rule}\\ &=2 \sec^{2}(\theta) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) & \text{derivative of }\tan(\theta) = \sec^{2}(\theta) \end{align*}\]

Substituting \(\dfrac{dh}{dt} = 5\) and \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\) into the related rates equation and solving for \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\), we get

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dh}{dt} & =2 \sec^{2}(\theta) \left ( \dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right )\\ 5 & =2 \sec^{2}\left (\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) \end{align*}\]

Since \(\sec^{2} = \frac{1}{\cos^{2}}\), if we multiply both sides of the equation by \(\cos^{2}\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right)\), we get

\[5\left(\cos\left(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right)\right)^{2}=2\left ( \dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right )\]

The \(\cos\left(\frac{\pi}{4}\right) = \frac{1}{\sqrt2}\), and so we get

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{5}{2} \left(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)^{2} &= \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} \\ \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} & =\dfrac{5}{4} \end{align*}\]

Now what are the units of this rate?

Since the change in height, \(\dfrac{dh}{dt}\), is measured in km/h, the time is measured in hours.

Since \(\theta\) is measured in radians, the rate \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\) is measured in radians per hour.

Therefore, the angle \(\theta\) is increasing (since the rate is positive) at a rate of \(\dfrac{5}{4}\) radians per hour when \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{4}\).

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Example 2—Part B

A hot air balloon rises straight up from the ground. An observer located \(2\) km away from the balloon's launching point is tracking the balloon through a telescope. Let \(\theta\) be the angle between the sight line of the telescope and the ground, measured in radians. Given that the balloon is rising at a constant rate of \(5\) km/h, calculate the following quantity:

At what rate is the angle \(\theta\) changing when the balloon is \(4\) km high?

Solution

Here, we can use the same related rates equation as in part a), but this time we're asked to find a different value.

Given: \(\dfrac{dh}{dt} = 5\) km/h.

Find: \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\) when \(h = 4\).

Since we have \(\dfrac{dh}{dt} = 2 \sec^{2}(\theta) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right )\), we need the value of \(\theta\) corresponding to \(h=4\).

How do we find this value? Well, we go back to our principal formula.

Recall that \(h\) and \(\theta\) always satisfy the relationship \(h = 2 \tan(\theta)\). So if \(h = 4\), using the principal equation, we get

\[h = 2 \tan(\theta) \Longrightarrow 4= 2 \tan(\theta) \Longrightarrow \tan(\theta) = 2\]

Since, from the physical situation, it's pretty clear that \(0 \leq \theta \leq \frac{\pi}{2}\), we have \(\theta = \tan^{-1}(2) \approx 1.107\).

Substituting the given values into the related rates equation, we can solve for \(\frac{d\theta}{dt}\):

\(\begin{align*} 5 & = 2 \sec^{2}(\tan^{-1}(2)) \left (\tfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) \\ \tfrac{d\theta}{dt} & =\tfrac{5}{2} \cos^{2}\Big(\tan^{-1}(2)\Big) \end{align*}\)

So how do we find the exact value of this expression?

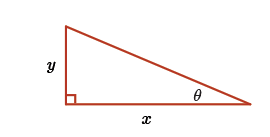

Consider the expression \(\cos\Big(\tan^{-1}(2)\Big)\) and the given diagram.

Here we have a right angle triangle with one angle \(\theta\) and the two legs of the triangle denoted by \(x\) and \(y\).

If \(\tan(\theta) = 2\), then what is the value of \(\cos(\theta)\)? To find this, of course we need to find the length of the hypotenuse.

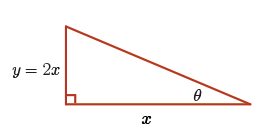

From the given triangle, we have \(\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{y}{x} =2\) and hence \(y = 2x\).

Using the Pythagorean theorem, we can find an expression for the hypotenuse of the triangle. More specifically, it's equal to the square root of the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

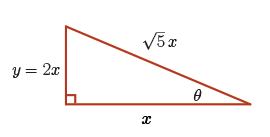

\[\begin{align*} \text{hypotenuse} & = \sqrt{x^{2} + (2x)^{2}} \\ &= \sqrt{x^{2} + 4x^{2}} \\ &= \sqrt{5x^{2}} \\ &=\sqrt{5}x \end{align*}\]

since \(x \gt 0\) (\(x\) is the length, so it's positive).

Therefore, we have \(\cos(\theta)= \dfrac{\text{adjacent}}{\text{hypotenuse}} = \dfrac{x}{\sqrt{5}x} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\).

So, if \(\tan(\theta) = 2\) and \(0 \lt \theta \lt \dfrac{\pi}{2}\), then \(\cos(\theta) = \cos\Big(\tan^{-1}(2)\Big) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\), and hence, when we substitute this value into our related rates equation from this problem, we get

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{d\theta}{dt} & = \dfrac{5}{2} \cos^{2}\Big(\tan^{-1}(2)\Big) \\ & = \dfrac{5}{2} \left(\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{5}}\right)^{2} \\ & =\left (\dfrac{5}{2}\right)\left(\dfrac{1}{5}\right ) \\ & = \dfrac{1}{2} \end{align*}\]

Therefore, the angle \(\theta\) is increasing at a rate of \(0.5\) radians per hour.

Note that if you use your calculator to approximate the value of \(\tan^{-1}(2)\), say to three decimal places, then you'll get \(1.107\) and we'll get a final answer of \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} \approx 0.5\).

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 3—Part A

A particle moves along the curve \(y = x^{2}\ln(x)\).

Suppose that the \(x\)-coordinate of the particle is increasing at a constant rate of \(2\) units per second.

So here we're given a curve and we're given a particle moving along this curve. Since its \(x\)-coordinate is increasing, this particle is moving to the right along this curve.

What is the rate of change of the \(y\)-coordinate of the particle at the instant the particle passes through the point \((1,0)\)?

Solution

So if we substitute \(x = 1\) into the equation for this curve, we indeed get \(y = 0\). So the point \((1, 0)\) does lie on this curve. As our particle moves to the right, at some point it's going to pass through this point on the curve. We're given that the \(x\)-coordinate is increasing at a constant rate, but what about the \(y\)-coordinate? Here's the solution.

The related quantities in this problem are the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates of the particle.

They are both changing with respect to time as the particle moves along the curve.

Given: \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = 2\) units per second.

Find: \(\dfrac{dy}{dt}\) when \(x=1\).

Relationship: \(y = x^{2}\ln(x)\)

As usual, now we differentiate the principal equation with respect to time. Recall that \(x\) is a function of \(t\).

\[ \begin{align*}\dfrac{dy}{dt}&= \dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(x^{2}\ln(x)\Big) \\ &=x^{2}\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(\ln(x)\Big) + \ln(x)\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(x^{2}\Big) & \text{by the product rule} \\ &=x^{2} \left(\dfrac{1}{x}\right)\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) + \ln(x) (2x)\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt} \right )& \text{by the chain rule} \\ &= x \left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) + 2x \ln(x)\left ( \dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) \\ &= \Big(x + 2x \ln(x)\Big)\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) \end{align*} \]

Now, we want to find \(\dfrac{dy}{dt}\) when \(x = 1\). Substituting the values of \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = 2\) and \(x = 1\), we get

\[ \begin{align*}\dfrac{dy}{dt}&=\Big(x + 2x \ln(x)\Big)\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) \\ &= \Bigr(1 + 2(1) \ln(1)\Bigr)(2) \\ &=2 \end{align*} \]

Therefore, the \(y\)-coordinate is increasing at a rate of \(2\) units per second at the instant the particle passes through the point \((1,0)\). Notice that this is the same rate as the \(x\)-coordinate.

Example 3—Part B

A particle moves along the curve \(y = x^{2}\ln(x)\).

Suppose that the \(x\)-coordinate of the particle is increasing at a constant rate of \(2\) units per second.

At what rate is the distance between the particle and the origin changing when the particle passes through the point \((e, e^{2})\)?

Solution

First we verify that this point, \((e, e^{2})\), indeed lies on the curve. Since \(\ln(e) = 1\), we have \(y = e^2\) as desired.

Let \(D\) be the distance between the particle and the origin.

Then, of course, because the particle is moving, \(D\) is also changing with respect to time as the \(x\)- and \(y\)-coordinates change.

Given: \(\dfrac{dx}{dt} = 2\) units per second.

Find: \(\dfrac{dD}{dt}\) when \(x=e\). (In other words, when the particle passes through the point with \(x\)-coordinate \(e\).)

Relationship: For any point in the plane \(xy\), the distance between \(xy\) and the origin is calculated as \( D = \sqrt{(x-0)^{2} + (y-0)^{2}} = \sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}\).

Since \(y = x^{2}\ln(x)\), we could substitute this expression for \(y\) into the equation for \(D\) and get a formula for the distance in terms of only \(x\) as follows:

\[D = \sqrt{x^{2} + \Big(x^{2}\ln(x)\Big)^{2}} = \sqrt{x^{2} + x^{4} \ln^{2}(x)}\]

Now, if we look at this, we have a product of functions, composition of functions, and a square root. It appears that this function will be time consuming to differentiate with respect to time, so we will take a different approach here.

Let \(u = x^{2}+y^{2}\). Then, \(D = \sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}= \sqrt{u}\).

We need to differentiate this equation, implicitly, with respect to time. Remember that \(u\) is a function of \(x\) and \(y\), and hence a function of time.

By the chain rule and the power rule, we have

\[\frac{dD}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt}\Big(\sqrt{u}\Big) = \frac{d}{du}\Big(\sqrt{u}\Big) \left (\dfrac{du}{dt}\right ) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{u}} \left ( \frac{du}{dt}\right )\]

Substituting the expression \(u = x^{2}+y^{2}\) back into the equation, we get

\[ \begin{align*} \dfrac{dD}{dt} & = \dfrac{1}{2} \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}} \dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(x^{2}+y^{2}\Big) \\ & = \dfrac{1}{2\sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}}\left(2x\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) + 2y \left (\dfrac{dy}{dt}\right)\right) \\ & =\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}}\left(x\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right) + y \left (\dfrac{dy}{dt}\right)\right) \end{align*} \]

To find \(\dfrac{dD}{dt}\) when \(x=e\), we will need a value for \(x\), \(y\), the rate \(\dfrac{dx}{dt}\), and the rate \(\dfrac{dy}{dt}\). Now, given in the question are the values for \(x\), \(y\), and the rate \(\dfrac{dx}{dt}\), but we don't have the rate for \(y\). So we first need to find the rate of change \(\dfrac{dy}{dt}\) at this instant.

We can do so using the method from part a).

Given the related rates formula

\[\frac{dy}{dt} = \Big(x + 2x \ln(x)\Big)\left (\frac{dx}{dt}\right )\]

at \(x=e\) (and knowing the rate \(\frac{dx}{dt} = 2\)), we have

\[\begin{align*} \frac{dy}{dt} & = \Big(e + 2e \ln(e)\Big)(2) \\ & = (3e)(2) \\ & =6e \end{align*}\]

Here we have \(x = e\), \(y = e^2\), \(\frac{dx}{dt} = 2\), and \(\frac{dy}{dt} = 6e\), which we just calculated.

Substituting all of the values, we find

\[ \begin{align*} \dfrac{dD}{dt}=\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{x^{2} + y^{2}}}\left(x\left (\dfrac{dx}{dt}\right ) + y \left (\dfrac{dy}{dt}\right)\right)& = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{(e)^{2} + (e^{2})^{2}}}\Big((e)(2)+ (e^{2}) (6e)\Big) \\ & = \dfrac{2e + 6e^{3}}{ \sqrt{e^{2}+e^{4}}} \\ & = \dfrac{2e\left(1 + 3e^{2}\right)}{ \sqrt{e^{2}(1 + e^{2})}} \\ &= \dfrac{2e\left(1 + 3e^{2}\right)}{e\sqrt{1 + e^{2}}} \\ & = \dfrac{2(1 + 3e^{2})}{\sqrt{1+e^{2}}} \\ & \approx 15.99728934 \end{align*} \]

Therefore, the distance between the particle and the origin is increasing at a rate of approximately \(16\) units per second when the particle passes through the point \((e,e^{2})\).

It is a good exercise to repeat this problem by instead differentiating the function written as a function of \(x\) only

\[D = \sqrt{x^{2} + \Big(x^{2}\ln(x)\Big)^{2}} = \sqrt{x^{2} + x^{4} \ln^{2}(x)}\]

with respect to \(t\), substituting the values \(\dfrac{dx}{dt}\) and \(x=e\), and verifying that you get the same answer as above.

Lesson Part 5

Examples

Let's finish our coverage of this topic with one final example.

Example 4—Part A

Bailey and Roger are running around a circular track with an outer radius of \(15\) m and a track width of \(3\) m. Bailey is travelling on the outer edge of the track at a constant \(3\) m/s, and Roger is travelling on the inner edge of the track at \(2\) m/s. Suppose that Bailey starts at the North side of the track and moves counter-clockwise while Roger starts at the South side of the track and moves clockwise. Let \(O\) denote the centre of the track, \(B\) the position of Bailey, and \(R\) the position of Roger. After they start running, the vertices \(O\), \(B\), and \(R\) form a triangle as shown in the picture.

Now, since Bailey is running on the outer circle, the length of the segment \(BO\) is constant at \(15\) meters. Since Roger is running on the inner circle, the length \(RO\) is at a constant \(15 - 3\), or \(12\) meters. The third side of the triangle \(BR\) is changing with respect to time as they run. Similarly, the angle at the center between \(B\) and \(R\), \(\angle BOR\), is changing with respect to time.

Now, from the start of their race to the point where \(B\) and \(R\) cross on the track, we have a positive angle between the line segments \(BO\) and \(OR\). We're interested in the rate of change of this quantity.

Let \(\theta\) denote \(\angle BOR\). What is the rate of change of the angle \(\theta\)?

Solution

Now, notice here that we haven't given a particular instant where we're looking for the value of \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\). This is hinting that the angle should be changing at a constant rate.

First, we need to translate the rates given in meters per second into radians per second.

The circumference of the outer circle is \(2 \pi r =2\pi(15) =30 \pi\) m, and the circumference of the inner circle is \(2 \pi (12) = 24 \pi\) m.

Since Bailey travels \(3\) meters in \(1\) second, Bailey covers an angle of \(\frac{3}{30 \pi}\). So the corresponding angle that Bailey sweeps out is

\[\frac{3}{30 \pi}(2\pi) = \frac{1}{5}\]

radians in \(1\) second.

Similarly, since Roger travels \(2\) meters in \(1\) second, Roger covers an angle of

\[\dfrac{2}{24 \pi}(2\pi) = \dfrac{1}{6}\]

radians in \(1\) second.

Since Bailey and Roger are moving towards each other, the angle between them decreases by the sum of these two rates; that is

\[\frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{5} = \frac{11}{30}\]

radians per second.

Therefore, \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} = - \dfrac{11}{30}\) rad/s.

Lesson Part 6

Examples

Example 4—Part B

Bailey and Roger are running around a circular track with an outer radius of \(15\) m and a track width of \(3\) m. Bailey is travelling on the outer edge of the track at \(3\) m/s, and Roger is travelling on the inner edge of the track at \(2\) m/s. Suppose that Bailey starts at the North side of the track and moves counter-clockwise while Roger starts at the South side of the track and moves clockwise. Let \(O\) denote the centre of the track, \(B\) the position of Bailey, and \(R\) the position of Roger. After they start running, the vertices \(O\), \(B\), and \(R\) form a triangle as shown in the picture.

Let \(c\) be the length of the line segment \(BR\). At what rate is \(c\) changing when \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\)?

Solution

Now we've found that \(\theta\) is decreasing at a constant rate, but what about the length of this third changing side?

The related quantities in this question are the distance \(c\) and the angle \(\theta\).

Given: \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt} = -\dfrac{11}{30}\) rad/s (from part a)).

Find: \(\dfrac{dc}{dt}\) when \(\theta= \dfrac{\pi}{3}\).

Relationship:

Now what is the formula relating these two quantities? Well, let's look at the situation. Well, remember that we have this triangle \(BOR\).

We denote the side length \(BO\) by \(a\), the side length \(RO\) by \(b\), and of course \(c\) is our third side and \(\theta\) is \(\angle BOR\). We know that for any triangle, the sides and this angle \(\theta\) are related using the cosine law. More specifically, the cosine law is \(c^{2} = a^{2} + b^{2} - 2ab \cos(\theta)\).

While on this problem, remember that \(a\) is fixed and \(b\) is fixed, but \(c\) and \(\theta\) are changing. So let's substitute the values for \(a\) and \(b\), which are \(15\) and \(12\), respectively.

\[ \begin{align*} c^{2} & = 15^{2} + 12^{2} - 2(15)(12)\cos(\theta) \\ & = 369 - 360\cos(\theta) \end{align*} \]

Now we have our principal formula relating \(c\) and \(\theta\).

Next, we differentiate the principal equation with respect to time, using the chain rule, to get our related rates equation:

\[ \begin{align*} 2c \left (\dfrac{dc}{dt}\right) & = -360 (-\sin(\theta)) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) \\ & = 360 \sin(\theta) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) \end{align*} \]

We need the value of \(\sin(\theta) \left (\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right )\), which we have. But to calculate \(\dfrac{dc}{dt}\), we also need the values of \(c\), \(\theta\), and \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\), so we need to find the value of the distance \(c\) corresponding to \(\theta = \frac{\pi}{3}\).

Using the principal equation \(c^{2} = 369 - 360\cos(\theta)\) (from the cosine law), we get

\[ \begin{align*} c^{2} & = 369 - 360 \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{3}\right) \\ & = 369 - 360 \left(\frac{1}{2}\right) \\ &= 369 - 180 \\ &= 189 \end{align*} \]

and hence \(c = \sqrt{189} = \sqrt{9 \times 21} = 3 \sqrt{21}\) as \(c \gt 0\).

Substituting all of the known values and solving for \(\dfrac{dc}{dt}\) gives the following equations.

\[ \begin{align*} 2c \left ( \dfrac{dc}{dt}\right ) & =360 \sin(\theta) \left ( \dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\right ) \\ 2 \left(3 \sqrt{21} \right)\left ( \dfrac{dc}{dt}\right ) & =360 \sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{3}\right) \left(-\dfrac{11}{30}\right) \\ 6 \sqrt{21} \left ( \dfrac{dc}{dt}\right ) & =360 \left(\dfrac{\sqrt{3}}{2}\right) \left(-\dfrac{11}{30}\right) \\ \dfrac{dc}{dt} & =-\dfrac{11}{\sqrt{7}} \\ & = -\dfrac{11\sqrt{7}}{7} \end{align*}\]

Therefore, the distance, \(c\), between Bailey and Roger is decreasing at a rate of \(\dfrac{11\sqrt{7}}{7}\) m/s when \(\theta = \dfrac{\pi}{3}\).

Now in this question, we were only considering the cases when \(BOR\) forms a true triangle. You can imagine the very start of the race when \(B\) is at the north end of the track and \(R\) is at the south end of the track, we're really looking at a \(\theta\) equal to \(\pi\) or \(180 ^\circ\), and we don't have a true triangle here. Similarly, when \(B\) and \(R\) are closing in on each other and cross on the path, we would think of this angle \(\theta\) approaching \(0\).

So it's worth thinking about how this problem would change if we didn't restrict ourselves to the beginning of the race where \(\theta\) here is between \(0\) and \(\pi\), but we let the race continue, and we let these runners actually cross. So at any given time when the runners are going, let \(\theta\) be the angle between the segment \(BO\) and \(OR\) including \(0\) or \(\pi\). And let \(c\) always be the shortest straight line distance between \(B\) and \(R\).

In this case, does our principal formula from the cosine law hold at every time \(t\)? And so will differentiating this equation give us a relationship between their rates at any time \(t\)? Pay special attention to the rates \(\dfrac{d\theta}{dt}\) and \(\dfrac{dc}{dt}\) when the runners are closest, in other words, when \(\theta = 0\), and when the runners are farthest away, in other words, when \(\theta\) is equal to \(\pi\) or \(180 ^\circ\). This general problem would be worth some thought.