Lesson Part 1

In our explorations of using first principles to find the derivative, you may have noticed some patterns. For instance, when we differentiated quadratic functions, the derivative was always linear.

In This Module

- We will uncover patterns of differentiation, by differentiating general statements, to uncover a rule for finding the derivative without needing first principles.

Constant Function Rule

Suppose \(f(x) = c\), where \(c\) is any constant and \(c \in \mathbb{R} \).

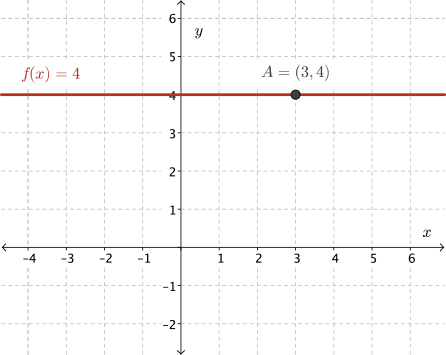

Let's examine the graph of \(f(x)=4\) to make predictions about the derivative.

If we were to draw a tangent to this function at the point \(A~(3,4)\), the tangent line would be horizontal and have a slope of \(0\).

This would be true of a tangent to any other point on \(f(x)\). This would also be true for any other constant function.

So, by this investigation, we may predict that the derivative of any constant function will be \(0\).

To prove that this statement is correct, we will use first principles.

Using first principles, find a general equation for differentiating constant functions.

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &=\displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\ &=\displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{c - c}{h} & \text{since} \ f(x) = c \ \text{and} \ f(x + h) = c \\ &= 0 \end{align*} \]

So the value of the slope of the tangent in this case is \(0\).

Therefore, when \( f(x)=c \), where \(c\) is any constant and \(c \in \mathbb{R} \), \( f'(x) = 0 \).

The Constant Function Rule

If \(f(x) = c\), for some constant \(c \in \mathbb{R}\), then

\[f'(x) = 0\]

In Leibniz notation, for some constant \( c \in \mathbb{R} \),

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(c\Big)=0\]

Example 1

Differentiate \(f(x) = 3\pi^2\).

Solution

Now \(\pi\) is a value. If we square that value and then multiply it by \(3\), we have a constant.

It follows that \(f(x)= 3\pi^2\) is a constant function. So when we differentiate, this function is going to equal \(0\).

Therefore, \(f'(x)=0\).

Power Rule

Suppose \(f(x) = x^r\) where \(r\) is any number in \(\mathbb{R}\).

Let's examine the graph of \(f(x)=x^3\) to make predictions about the derivative.

As we drag the point of tangency, \(A(x, f(x))\), from the left side of the graph along the curve towards the right, we notice that the slope of the tangent changes.

The points of the slope function are shown in red, \(f'(x) = 3x^2\).

What do you see? Do you notice a pattern in these values? Try this again for other cubic functions. How are the results the same? How are they different?

Investigation

See the investigation in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 2

Power Rule

You may have noticed that, when differentiating a polynomial function, the degree of the derivative was one less than the degree of the original polynomial. (One exception to this would be when taking the derivative of a constant polynomial.)

Let's use the first principles definition of the derivative to find a general equation for differentiating functions of the form \(x^n\), \(n\in \mathbb{N}\).

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\ &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h} \end{align*} \]

Now when we look at the numerator of this formula, we notice that there is a very large binomial that we're going to need to expand. In order to expand this binomial, we're going to need the following formula.

\[a^k-b^k=(a-b)(a^{k-1}+a^{k-2}b+a^{k-3}b^2+\cdots+a^2b^{k-3}+ab^{k-2}+b^{k-1})\]

Therefore, we know that

\((x + h)^n - x^n\)\[ \begin{align*} &= \left[(x + h) - x\right] \left[(x+h)^{n-1} + (x+h)^{n-2}(x) + \cdots + (x+h)(x^{n-2}) + x^{n-1}\right] \\ &= h\underbrace{\left[(x+h)^{n-1} + x(x+h)^{n-2} + \cdots + x^{n-2}(x+h) + x^{n-1}\right]}_{(n \text{ terms})} \end{align*} \]

We will now use this binomial expansion within our formula for first principles.

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\ &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{(x+h)^n-x^n}{h} \\ &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{h\left[(x+h)^{n-1} + x(x+h)^{n-2} + \cdots + x^{n-2}(x+h) + x^{n-1}\right]}{h} \end{align*} \]

Notice the factor of \(h\) in the numerator and denominator. We will divide this factor and simplify.

\[f'(x)= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \left[(x+h)^{n-1} + x(x+h)^{n-2} + \cdots + x^{n-2}(x+h) + x^{n-1}\right] \]

Once we have simplified, we can now evaluate the limit by substituting \(0\) in for \(h\), and simplify until we have a sum of terms.

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= (x+0)^{n-1} + x(x+0)^{n-2} + \cdots + x^{n-2}(x+0) + x^{n-1} \\ &= x^{n-1} + x(x)^{n-2} + \cdots + x^{n-2}(x) + x^{n-1} \\ &= \underbrace{\left(x^{n-1} + x^{n-1} + \cdots + x^{n-1} + x^{n-1}\right)}_{n \text{ terms}} \\ &= nx^{n-1} \end{align*} \]

While this is only the proof for \(f(x)=x^n\) where \(n \in \mathbb{N}\), this rule is also true for \(f(x)=x^r\) where \(r \in \mathbb{R}\). The reason this proof is only true for natural numbers is because of our use of the binomial expansion.

Unfortunately, we will need to explore more mathematical concepts before examining this proof with real values.

The Power Rule

If \( f(x) = x^r \), for \( r \in \mathbb{R} \), then

\[f'(x) = rx^{r-1}\]

In Leibniz notation,

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(x^r\Big)=rx^{r-1}\]

Example 1

Differentiate \( f(x) = \dfrac{1}{x^4}\).

Solution

When you look \(f(x)\), you may be wondering how this connects with the Power Rule. But remember that \( f(x) = \dfrac{1}{x^4}\) can be written as a power of \(x\) with a negative exponent, i.e., \( f(x) = x^{-4}\). Once in this form, we can apply the Power Rule.

Here, \(r=-4\) and \( f'(x) = rx^{r-1}\), so

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= (-4)x^{(-4-1)} \\ &= -4x^{-5} \\ &= -\dfrac{4}{x^{5}} \end{align*} \]

Therefore, \(f'(x) = -\dfrac{4}{x^{5}}\) is the derivative of our function.

Try Example 2 on your own, and then follow through this solution.

Example 2

Differentiate \( f(x) = \sqrt{x^5} \).

Solution

To differentiate this function, we need to recall how we can write a square root using exponents. Square root is the same as applying the exponent \(\frac{1}{2}\).

We can write \( f(x) = \sqrt{x^5} \) as a power of \(x\) with a rational exponent.

Here, \(f(x) = \sqrt{x^5} = \left(x^{5}\right)^{\frac{1}{2}} =x^{\frac{5}{2}}\)

So \(r =\dfrac{5}{2}\) and

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \left(\dfrac{5}{2}\right)x^{\frac{5}{2}-1} \\ &= \dfrac{5}{2} x^{\frac{3}{2}} \\ &=\dfrac{5\sqrt{x^3}}{2} \end{align*} \]

Lesson Part 3

What happens if we take a function and we multiply that function by a constant? How will the derivative change?

Functions Multiplied by a Constant

Suppose \(f(x) = cg(x)\), where \(c\) is any constant in \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(g(x)\) is any function.

Let's examine the graphs of \(f(x)=x^3\), \(f(x)=2x^3\), and \(f(x)=\dfrac{1}{2}x^3\) and their graphs of slopes of tangents to each curve to make predictions about how the derivative is modified by a multiplied constant.

As we look at these three graphs, it appears that for \(g(x)=2f(x)\), we have \(g'(x)=2f'(x)\); similarly, for \(h(x)=\dfrac{1}{2}f(x)\), we have \(h'(x)=\dfrac{1}{2}f'(x)\).

That is for \(y=af(x)\), the factor \(a\) which stretches \(f(x)\) vertically is the same factor which stretches \(f'(x)\) vertically.

Let's use the first principles definition of the derivative to find a general equation for differentiating functions with constant multiples.

When \( f(x) = cg(x) \), where \( c \in \mathbb{R} \) is a constant,

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h} \\ &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{c g(x+h) - c g(x)}{h} \end{align*} \]

When we look at the numerator, we notice that there is a common factor of \(c\) in both terms. Let's remove this common factor.

\[f'(x) = \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \left(c \left[\dfrac{g(x+h) - g(x)}{h}\right] \right)\]

Once we've removed this common factor of \(c\) from both terms, we can apply limit property four from our discussion on the properties of limits to remove this common factor from inside the limit.

Once the common factor of \(c\) has been removed from inside the limit, we see the formula for \(g'(x)\) inside the brackets.

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= c \underbrace{ \left(\displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{g(x+h) - g(x)}{h}\right) }_{g'(x)} \\ &= cg'(x) \end{align*} \]

So the derivative of \(f(x)\) is \(cg'(x)\).

The Constant Multiple Rule

If \( f(x) = c g(x) \), for some differentiable function, \(g(x)\), and \( c \in \mathbb{R} \), then

\[f'(x) = cg'(x)\]

In Leibniz notation, for some constant \( c \in \mathbb{R} \),

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(cy\Big)=c\dfrac{dy}{dx}\]

Consider the following example. Try a solution on your own using the constant multiple rule, and possibly also another rule that we've explored in this module. Then follow through the solution.

Example 3

Differentiate \( f(x) = \dfrac{5}{x^2}\).

Solution

We can write \(f(x)= \dfrac{5}{x^2}\) as \(f(x)=5x^{-2}\).

So by using the constant multiple rule, let \(g(x)=x^{-2}\), then \(f(x)=5g(x)\).

To differentiate, we know that \(f(x)=5x^{-2}\) differentiates to \(f'(x)=5g'(x)\), so

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= 5\left[(-2)x^{(-2-1)}\right] \\ &= 5\left(-2x^{-3}\right) \\ &= -\dfrac{10}{x^{3}} \end{align*} \]

Lesson Part 4

Sums and Differences of Functions

How do we differentiate the sum of two functions?

If \(f(x) = p(x)+q(x)\), how do we differentiate \(f(x)\)?

Let's use the first principles definition of the derivative and limit properties to find a general equation for differentiating the sum of functions.

\[f'(x) = \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}\]

\(f(x) = p(x) + q(x)\)

\(f(x + h) = p(x + h) + q(x + h)\)

Let's substitute these functions into our formula for first principles.

\[ \begin{align*} f'(x) &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{(p(x+h) + q(x+h)) - (p(x) + q(x))}{h} \\ &= \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{p(x+h) + q(x+h) - p(x) - q(x)}{h} \end{align*} \]

We're going to rearrange the terms in the numerator so that all of the functions of \(p\) are together and all of the functions of \(q\) are together.

\[f'(x) = \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{[p(x+h) - p(x)] + [q(x+h) - q(x)]}{h}\]

Once we have rearranged the numerator, we are able to split this into two fractions, each having denominator \(h\).

\[f'(x) = \displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \left(\dfrac{p(x+h) - p(x)}{h} + \dfrac{q(x+h) - q(x)}{h}\right) \]

If we think about limit property 3 from when we discussed properties of limits, we can apply this limit property here since we have one fraction added to another.

\[f'(x) = \underbrace{\displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{p(x+h) - p(x)}{h}}_{p'(x)} + \underbrace{\displaystyle \lim_{h \rightarrow 0} \dfrac{q(x+h) - q(x)}{h}}_{q'(x)} \]

Once the limit has been applied to each fraction separately, we notice that the first fraction is really \(p'(x)\) and the second fraction is \(q'(x)\). So rather than having this large expression, we could actually write this as \(p'(x) + q'(x)\).

\[f'(x) = p'(x) + q'(x)\]

So the derivative of the sum of two functions is equal to the sum of their derivative functions.

Similarly, we could differentiate \(f(x)=p(x)-q(x)\) to see that

\[f'(x)=p'(x)-q'(x)\]

The Sum and Difference Rule

If \( f(x) = p(x) + q(x) \) for some differentiable functions, \(p(x)\) and \(q(x)\), then

\[f'(x) = p'(x) + q'(x) \]

If \( f(x) = p(x) - q(x) \) for some differentiable functions, \(p(x)\) and \(q(x)\), then

\[f'(x) = p'(x) - q'(x)\]

In Leibniz notation,

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(u+v\Big)=\dfrac{du}{dx}+\dfrac{dv}{dx}\]

and

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(u-v\Big)=\dfrac{du}{dx}-\dfrac{dv}{dx}\]

Lesson Part 5

Combining Differentiation Rules

The previous rules can be used in combination with each other to quickly find the derivatives of many functions. The best way to become familiar with these rules is to practise.

Example

Let's now try the following challenge problem.

Challenge Problem

What is the maximum slope of a tangent to the function \(f(x)=-x^3+4x-2\)?

Solution

The slope of the tangent to \(f(x)=-x^3+4x-2\) is found by differentiating \(f(x)\).

\[f(x)=-x^3+4x-2\]

Using the derivative rules,

\[f'(x)=-3x^2+4\]

Therefore, the slope of any tangent to the function, \(f(x)=-x^3+4x-2\), is found by the formula \(m_{tangent}=-3x^2+4\).

Now let's consider this function in more detail.

The function \(f'(x)=-3x^2+4\) is a downward opening quadratic with vertex \((0,4)\), therefore its maximum value is \(4\).

Thus, the maximum slope of the tangent to the function \(f(x)=-x^3+4x-2\) is \(4\).

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.