Lesson Part 1

Recall

Well, welcome to the second unit on vectors. In the first unit on vectors, we were introduced to quantities having both magnitude and direction. These were called geometric vectors, and now we're going to look at what are called algebraic vectors. We considered their geometric representation as a directed line segment or arrow.

In This Unit

- We will introduce vectors in an \(xy\)-plane, a Cartesian coordinate system and consider the convenience that this new model provides.

- We will refer to these as algebraic vectors otherwise called vectors in component form.

Algebraic Vectors

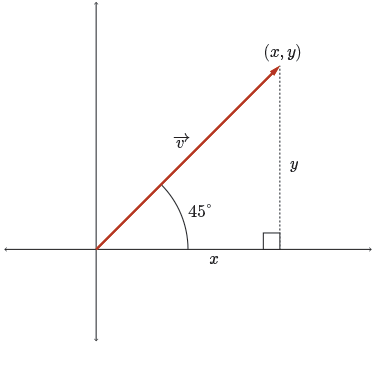

Vector \(\vec{v}\) is defined to have magnitude \(10\) and a direction of north \(45^\circ\) east. This vector, \(\vec{v}\), is an example of a geometric vector.

This was a typical representation of the concept throughout the first vector unit.

Question: Can we represent the same vector, \(\vec{v}\), in a different way?

Answer: If the answer to this question was no, this would be an awfully short unit on vectors. Yes, by using the notion of algebraic vectors.

To represent a geometric vector algebraically, position the tail of the vector, \(\vec{v}\), at the origin of a Cartesian \(xy\)-plane.

In our case, \(\lvert \vec{v}\rvert=10\) and the direction is north \(45^\circ\) east, which corresponds to an angle of \(45^\circ\) CCW (counter-clockwise) from the positive \(x\)-axis (this is defined as standard position). The question is how is this different? What is the advantage? It really looks like the same representation as the first unit.

Well, it turns out we can now represent vector \(\vec{v}\) using coordinates \(x\) and \(y\), where \((x,y)\) is the location of the tip of vector \(\vec{v}\) when its tail is positioned at the origin.

This raises the question: How do we find the coordinates \(x\) and \(y\) given the magnitude of the vector and its direction?

Again, as has often been the case in our study of vectors thus far, along comes trigonometry. We have a right triangle this time. Nice. So we can employ SOH CAH TOA or whatever acronym you use.

The cos of \(45^{\circ}\) is adjacent over hypotenuse. Adjacent is \(x\). The hypotenuse is the magnitude of \(\vec{v}\).

\[\begin{align*} \cos(45^\circ) &= \dfrac{x}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}\\ \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} &= \dfrac{x}{10}\\ \dfrac{10}{\sqrt{2}} &= x \qquad \text{(rationalize the denominator)}\\ x &= 5\sqrt{2} \end{align*}\]

Similarly, we could say that the sine of \(45^{\circ}\) is opposite over hypotenuse. That's \(y\) over the magnitude of vector \(v\). And we get the same result.

\[\begin{align*} \sin(45^\circ) &= \dfrac{y}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}\\ \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} &= \dfrac{y}{10}\\ \dfrac{10}{\sqrt{2}} &= y \qquad \text{(rationalize the denominator)}\\ y &= 5\sqrt{2} \end{align*}\]

Well, we didn't really need trigonometry there. We have a \(45^{\circ}\) angle in this right triangle, so it's an isosceles right triangle. That is, \(x = y\). So it makes sense that \(y\) is also \(5\sqrt{2}\). Or alternatively, we could have used the ratio of the sides of this \(1\sqrt{2}\) triangle to get the value of \(y\).

Therefore, vector \(\vec{v}\) can be written algebraically as an ordered pair \((5\sqrt{2},5\sqrt{2})\).

The ordered pair \((5\sqrt{2},5\sqrt{2})\) is an example of an algebraic vector.

In the ordered pair, \(x=5\sqrt{2}\) and \(y=5\sqrt{2}\) are referred to as the \(x\) and \(y\) components of the vector \(\vec{v}\). As a result, \(\vec{v}=(5\sqrt{2},5\sqrt{2})\) may be said to be in component form.

So at this point, you might be thinking, wow, we have this ordered pair, \((5\sqrt{2},5\sqrt{2})\), and it represents a vector. But it would also represent a point in the \(xy\)-plane. So how will I know which it is? If I'm given an ordered pair \((x,y)\), how do I know if it means a vector or a point? And well, the truth is that the context in which the ordered pair is provided will give away the game, whether we're talking about a vector or an ordered pair or a point in the plane.

The position vector of a point \(P\) is the vector \(\overrightarrow{OP}\) with tail at the origin \(O\) and tip at the point \(P\).

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Example 1

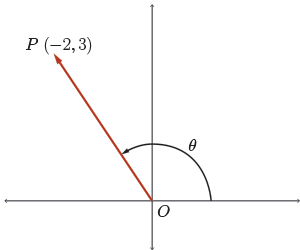

Draw vector \(\overrightarrow{OP} = (-2,3)\) and determine its magnitude and direction.

Solution

We begin by drawing a picture. Place \(\overrightarrow{OP}\) on the \(xy\)-plane. \(P\) is at \((-2, 3)\).

We want to find angle \(\theta\) (its direction), remember, in standard position here, that's going to be measured from the positive \(x\)-axis. We are also asked to find the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{OP}\).

Well, the magnitude is easy. We just find the length of the segment \(OP\). \(O\) again is the origin, \((0,0)\). \(P\) is \((-2, 3)\). We can use our length formula.

\[\begin{align*} \lvert \overrightarrow{OP} \rvert &= \sqrt{(\Delta{x})^2+(\Delta{y})^2}\\ &= \sqrt{(-2)^2+(3)^2} \\ &= \sqrt{13} \end{align*}\]

We get \(\sqrt{13}\) as the magnitude of the vector.

Then we use a little bit of trigonometry. We solve the equation \(\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{3}{-2}\). Recall \(\tan{\theta}\) is opposite over adjacent.

\[\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{3}{-2} \implies \theta \approx 124^\circ\]

Now we have to do a little bit of work here. Notice that a calculator would return \(\theta = \tan^{-1} \left (\dfrac{3}{-2} \right) \approx -56^\circ\). If we typed in \(\theta = \tan^{-1} \left (\dfrac{3}{2} \right)\), we'd get positive \(56\) degrees. Thus, we must consider which quadrant the vector lies in so that this \(56^{\circ}\) angle that our calculator returns is the related acute angle. That is the angle between our vector and the \(x\)-axis. So therefore \(\theta\) is its supplement. Thus, \(\theta = 180^\circ -56^\circ= 124^\circ\).

Therefore, \(\lvert \overrightarrow{OP} \rvert = \sqrt{13}\) and \(\overrightarrow{OP}\) makes an angle of \(124^\circ\) with the positive \(x\)-axis.

In general, any vector, \(\vec{u}\), can be written as an ordered pair \((a,b)\) where

\[\lvert \vec{u} \rvert = \sqrt{a^2+b^2} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad \theta=\tan^{-1} \left ( \dfrac{b}{a} \right)\]

Note that \(\theta\) is an angle measured CCW from the positive \(x\)-axis.

When solving for \(\theta = \tan^{-1} \left (\dfrac{b}{a}\right)\), there are two possible solutions for \(0^\circ \leq \theta \leq 360^\circ\). The quadrant that \((a,b)\) lies in will determine the correct \(\theta\).

Consider what happens when \(a = 0\) or \(b = 0\). When \(b = 0\), the point \(P\) becomes \((a,0)\) where \(a\neq 0\). And it lies on the positive \(x\)-axis when \(a \gt 0\), in which case, \(\theta = 0\) degrees. And similarly, \(P\) would lie on the negative \(x\)-axis when \(a \lt 0 \). And in that case, \(\theta\) would equal \(180\) degrees. So consider when \(a = 0\), the point \(P\) becomes \((0, b)\), again \(b \neq 0\) this time. And point \(P\) would lie on the positive \(y\)-axis for \(b\) greater than \(0\), in which case \(\theta = 90^{\circ}\). And \(P\) would lie on the negative \(y\)-axis for \(b \lt 0\), in which case \(\theta = 270^{\circ}\).

Lesson Part 3

Unit Vectors

Let's look at unit vectors again. We discussed this in the first unit. A unit vector, if you recall, is just a vector with magnitude \( 1 \), or length \( 1 \).

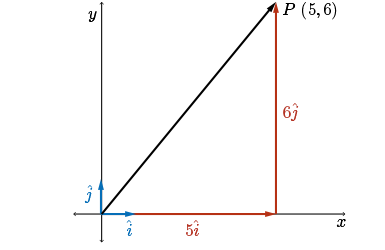

The special unit vectors which point in the direction of the positive \(x\)-axis and positive \(y\)-axis are given the names \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) respectively, where \(\hat{i}=(1,0)\) and \(\hat{j}=(0,1)\).

We may express any vector in the \(xy\)-plane as a sum of scalar multiples of the vectors \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\).

For example, the vector \(\overrightarrow{OP}=(5,6)\) can be expressed as a vector sum of scalar multiples of \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) in the following manner:

\[\overrightarrow{OP} = (5,6) = 5\hat{i} +6\hat{j}\]

In our diagram, we are going to scale \(\hat{i}\) by \(5\), scale \(\hat{j}\) by a factor of \(6\), and the vector sum of \(5\hat{i}\) and \(6\hat{j}\) will give us \(\overrightarrow{OP}\).

In general, ordered pair notation and unit vector notation are equivalent.

Any algebraic vector can be written in either form:

\[\vec{u} = \overrightarrow{OP} = (a,b)\]

which is a position vector, or

\[\vec{u}=\overrightarrow{OP} = a\hat{i} + b\hat{j}\]

which we call unit vector notation.

Vectors in \(3\) Dimensions

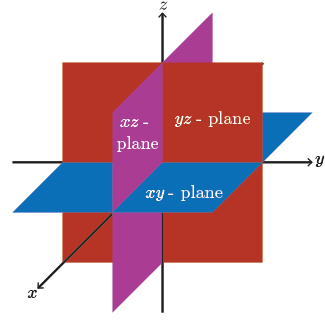

Previously, we had considered geometric and algebraic vectors in the \(2\)-dimensional (Cartesian) plane. This model extends naturally to \(3\) dimensions.

Consider the \(2\)-D \((xy)\) Cartesian plane comprised of the \(x\) and \(y\) axes.

If we add a third axis (\(z\)-axis) to our existing \(xy\)-plane such that all \(3\) axes are mutually perpendicular to one another, we create a coordinate system which models \(3\)-dimensional space.

To visualize this, you might consider, for a moment, just looking into the corner of the room that you're sitting in. If you look into the corner of the room that you're in, I'm going to assume that you are not in a round room, then the very bottom of that corner, extending out to your left, we might call that the positive \(x\)-axis. Extending to the right, where the wall meets the floor, that would be the positive \(y\)-axis. And extending from the corner upward would be the positive \(z\)-axis.

A plane that contains two of the axes is known as a coordinate plane. For example, the plane containing the \(x\)- and \(z\)-axes is the \(xz\)-plane.

To plot the \(3\)-dimensional point with coordinates \((a,b,c)\), move \(a\) units from the origin in the \(x\)-direction, \(b\) units in the \(y\)-direction, and \(c\) units in the \(z\)-direction.

Investigation 1

See the investigation in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 2

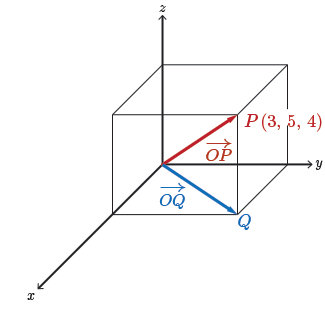

Locate the point \(P~(3,5,4)\) and sketch the position vector \(\overrightarrow{OP} = 3\hat{i}+5\hat{j}+4\hat{k}\), where \(\hat{i}=(1,0,0), \hat{j}=(0,1,0)\), and \(\hat{k}=(0,0,1)\) are the special unit vectors pointing in the direction of the positive \(x\)-, \(y\)-, and \(z\)-axes, respectively. That is, we've extended \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) from our two-dimensional space into three dimensions, the \(z\) coordinate is \(0\) for \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\). We've introduced a new unit vector \(\vec{k}\). This time it is in the direction of the positive \(z\)-axis. Calculate the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{OP}\).

Solution

Draw a sketch of \(\overrightarrow{OP}\). Again, its a position vector. \(O\) is at the origin. I've drawn here the rectangular prism. I'm trying to find the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{OP}\). Consider adding a point \(Q\) to this diagram. \(Q\) would be directly below point \(P\) in the \(xy\)-plane.

Note: The \(x\) and \(y\) coordinates help form the bottom (if \(z\) is positive) or the top (if \(z\) is negative) of the rectangular prism.

If I want to find the magnitude of \(\overrightarrow{OQ}\), well, \(\overrightarrow{OQ}\) is a hypotenuse of a right triangle on the \(xy\)-plane. So

\[ \begin{align*} \lvert\overrightarrow{OQ}\rvert^2 &= 3^2 + 5^2 \\ \lvert {\color{NavyBlue}\overrightarrow{OQ}}\rvert &= \sqrt{3^2+5^2} =\sqrt{34} \end{align*} \]

\(\overrightarrow{OQ}\) is perpendicular to \(\overrightarrow{PQ}\). That is, we have another right triangle, thus, by the Pythagorean theorem

\[\lvert {\color{BrickRed}\overrightarrow{OP}}\rvert^2 = \lvert{\color{NavyBlue}\overrightarrow{OQ}}\rvert^2 + \lvert\overrightarrow{PQ}\rvert^2\]

Observe \(\lvert {\color{NavyBlue}\overrightarrow{OQ}}\rvert^2 = 3^2+5^2=34\) and \(\lvert \overrightarrow{PQ}\rvert^2=4^2=16\), then

\[ \begin{align*} \lvert {\color{BrickRed}\overrightarrow{OP}}\rvert^2 &= 3^2+5^2+4^2 \\ \lvert {\color{BrickRed}\overrightarrow{OP}}\rvert &= \sqrt{3^2+5^2+4^2} = \sqrt{50} =5\sqrt{2} \end{align*} \]

It's two applications of the Pythagorean theorem, or one application of the Pythagoras in \(3\)-space. In general, if \(\overrightarrow{u}=(a,b,c)\), then \(\lvert \overrightarrow{u}\rvert = \sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}\).

Lesson Part 5

Direction Angles

Next we want to talk about what are called direction angles. In \(2\) dimensions, the direction of a vector is given by a single angle, as we previously saw. In \(3\) dimensions, the direction of a vector is given by \(3\) angles, called direction angles. Sometimes they are called directional cosines.

Image description: A dotted rectangle is drawn in \(3\) dimensional space. The rectangle is bound by a vertex at the origin and a vertex at the point \(P(a,b,c)\). Label the height of the rectangle along the \(z\)-axis as \(c\).

The direction angles of vector \((a,b,c)\) are \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), and \(\gamma\), which are the angles the vector makes with the positive \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\) axes, respectively.

These angles are restricted to be

\[0^\circ \leq \alpha, \beta, \gamma \leq 180^\circ\]

For example, let's say, for argument's sake, that I am asked to find the direction of angle \(\gamma\), that is, the angle between vector \((a,b,c)\) and the \(z\)-axis. Well, I can extract the right angle triangle with hypotenuse equal to the magnitude of the \(\overrightarrow{OP}\) and side length \(c\), that is, the \(z\)-coordinate of vector \((a,b,c)\). Then, the angle gamma is given by

\[\cos(\gamma) =\dfrac{c}{\lvert \overrightarrow{OP}\rvert}\]

Similarly, we can find the angle between the vector and the \(x\)-axis and the angle between the vector and the \(y\)-axis. All we have to do is change the component from \(c\) to \(a\) in the \(x\) case and \(b\) in the \(y\) case, as shown.

\[\cos(\alpha)=\dfrac{a}{\lvert \overrightarrow{OP} \rvert} \qquad \cos(\beta)=\dfrac{b}{\lvert\overrightarrow{OP}\rvert}\]

Investigation 2

See the investigation in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 6

Examples

Example 3

Find the direction angles of the vector \(\vec{u}=(-2,3,0)\).

Solution

Using the definition of the direction angles,

\[\begin{align*} \cos{\alpha} &= \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{u}\rvert}\\ &= \dfrac{-2}{\sqrt{(-2)^2+3^2+0^2}}\\ &= \dfrac{-2}{\sqrt{13}}\\ \therefore \alpha &\approx 124^\circ \end{align*}\]

We repeat the process to find \(\cos{(\beta})\), which is \(b\) over the magnitude.

\[\begin{align*}\cos(\beta) &= \frac{b}{\lvert \vec{u}\rvert} = \frac{3}{\sqrt{13}} \\ \therefore \beta &\approx 34^\circ\end{align*}\]

In a similar way, for \(\cos{(\gamma)}\) we find the angle between the vector, \(u\), and the positive \(z\)-axis.

\[\begin{align*}\cos(\gamma) &= \frac{c}{\lvert \vec{u}\rvert}= \frac{0}{\sqrt{13}} \\ \therefore \gamma &= 90^\circ\end{align*}\]

Not surprising since this vector, \((-2, 3, 0)\), lies in the \(xy\)-plane and \(z\) coordinate is \(0\). So it makes a lot of sense, then, that \(\gamma\) was equal to \(90^{\circ}\) in this example.

Example 4

Find a unit vector in the direction of \(\vec{v}=(a,b,c)\) and prove that \(\cos^2(\alpha) +\cos^2(\beta)+\cos^2(\gamma)=1\), where \(\alpha, \beta,\gamma\) are the direction angles of \(\vec{v}\).

Solution

We are asked to find a unit vector which, by definition, has magnitude \(1\).

Recall from our first module in the first unit on vectors, we claimed that to create a unit vector in the direction of \(\vec{v}\), we have to multiply \(\vec{v}\) by the scalar equal to the reciprocal of the magnitude of \(\vec{v}\).

That is, \(\hat{v}=\dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}\vec{v}\) is a unit vector in the direction of \(\vec{v}\).

Well, back in the first unit on vectors we didn't actually prove this. You just had to take my word for it. But we should have a look at this a little bit more closely at this point. So we know the magnitude of \(\vec{v} = \sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}\). So we want to check that if we take \(\vec{v}\) and we multiply it by \(1\) over the magnitude of \(\vec{v}\) that we actually get a vector of length \(1\). Let's check that our claim is true.

\[\dfrac{1}{\lvert\vec{v}\rvert} (\vec{v}) = \dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (a,b,c)\]

So \(1\) over magnitude of \(v\) times vector \(a,b,c\) gives us \(a\) over the magnitude of \(v\)

\[\dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (a,b,c) = \left ( \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right)\]

This gives us \(a\) over \(\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}\), and likewise for the other two components of the vector, that's \(b\) over the magnitude and \(c\) over the magnitude.

\[\left ( \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right) = \left (\dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}},\dfrac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}},\dfrac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} \right)\]

We want to check what the magnitude of this new vector is. Well, that's not hard to do. Recall that we will take each of these components, and we're going to square them and add them and then take the square root of the sum.

\[\left \lvert \dfrac{\vec{v}}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right \rvert = \left \lvert \left ( \dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}, \dfrac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}},\dfrac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}} \right ) \right \rvert\]\[= \sqrt{\left ( \dfrac{a}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\right )^2+\left ( \dfrac{b}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\right )^2+\left ( \dfrac{c}{\sqrt{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\right )^2}\]\[= \sqrt{\left ( \dfrac{a^2}{a^2+b^2+c^2} \right)+\left ( \dfrac{b^2}{a^2+b^2+c^2} \right)+\left ( \dfrac{c^2}{a^2+b^2+c^2} \right)}\]

We get a common denominator of \({a^2+b^2+c^2}\), which turns out to be our numerator.

\[= \sqrt{\dfrac{a^2+b^2+c^2}{a^2+b^2+c^2}}\]

Notice that the magnitude of this new vector is \(1\), as we had previously claimed.

\[=1\]

Thus, our new vector is indeed a unit vector.

It was also required that this new vector be in the same direction as \(\vec{v}\).

Since \(\dfrac{1}{\lvert\vec{v}\rvert}\) is a positive scalar, then \(\dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (a,b,c) = \dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}(\vec{v})\) is in the same direction as \(\vec{v}\).

Therefore, the vector, \(\hat{v}=\dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (\vec{v})\), is indeed a unit vector in the direction of \(\vec{v}\), as previously claimed.

What's left is to prove that the \(\cos(\alpha) + \cos(\beta) + \cos(\gamma)\) is equal to \(1\), where again, alpha, beta, and gamma are the direction angles of \(\vec{v}\).

Since \(\hat{v} = \dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (\vec{v}) = \dfrac{1}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} (a,b,c) = \left ( \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert}, \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right)\) is indeed a unit vector, then

\(\begin{align*}\sqrt{\left( \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert} \right )^2+\left( \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert} \right )^2+\left( \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert} \right )^2 } &=1 \end{align*}\)

So if we now look inside the brackets, the round brackets that is, we have \(a\) over the magnitude of \(v\), \(b\) over the magnitude of \(v\), and likewise for \(c\).

\(\begin{align}\left ( \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right )^2 + \left ( \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right )^2 + \left ( \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v}\rvert} \right )^2 &=1\end{align}\)

But recall that the direction angles are given by

\[\cos(\alpha) = \dfrac{a}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert } \qquad \cos(\beta) = \dfrac{b}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert } \qquad \cos(\gamma) = \dfrac{c}{\lvert \vec{v} \rvert }\]

Substituting these into (1), we get \(\cos^2(\alpha)+\cos^2(\beta)+\cos^2(\gamma)=1\), where \(\alpha, \beta,\gamma\) are the direction angles of \(\vec{v}\), as required.

Well, if you've made it to this point and followed all of that, good for you. That was a lot of material, but we're at the end. Thanks for listening.

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.