Lesson Part 1

Evaluating Limits of Convergent Sequences

A sequence is a function whose domain is the set of positive integers \(n=1,2,3,\ldots\).

The values or individual terms of a sequence are generally denoted by a subscript of \(n\) on \(t\). In other words, we use \(t_n\) rather than \(f(n)\).

For example, the list of all positive odd numbers forms the sequence \(1,3,5,7,\ldots\).

This sequence could be represented algebraically by two different formulas:

\[t_n=t_{n-1}+2 \text{ where } t_1=1\]

This recursive formula tells us that we just need to add \(2\) to the previous term in order to get the term we are trying to calculate. For instance, if the first term is one, then to get term two, we take term one and add \(2\). So to calculate the \(n^{th}\) term, we take the \(n - 1\) term, in other words, the term coming previous to the \(n^{th}\) term and add \(2\). Try this now for the list of positive odd numbers in the above sequence.

\[\begin{align*} t_n&=1+2(n-1) \\ &=2n-1 \text{ for } n=1,2,3,\ldots \end{align*}\]

We could also use an arithmetic formula to define the sequence. Here the \(n^{th}\) term is calculated by taking \(1\) and adding \(2\) times the quantity of \(n - 1\). Here again, \(n\) is the term number of the sequence. So if we wanted the fourth term, we substitute \(4\) in for the value of \(n\), and simplify this expression.

If we continue this sequence of numbers, would this sequence approach a single value?

In other words, as \(n\) becomes very, very large, meaning as \(n \to +\infty\) does \(t_n\) approach a limit? Remember, a limit is an approached value. As \(n\) increases, we see that \(t_n\) becomes arbitrarily large in value.

Therefore, as \(n \rightarrow + \infty\), \(t_n \rightarrow + \infty\). This means that as \(n\) approaches positive infinity, the \(n^{th}\) term approaches positive infinity.

We could use limits to write this as

\[\lim_{n \to +\infty} (2n-1) \to +\infty\]

The quantity \(2n - 1\) is a simplified version of the arithmetic formula we saw above. Notice how we did not use an equal sign between the limit and positive infinity. Again, infinity is not a value we can equal, but is a value that we can approach.

- Recursive Formula

- Arithmetic Formula

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Example 1—Part A

Consider the sequence defined by \(t_n=\dfrac{1}{n^2+4}\).

List the first five terms of this sequence.

Solution

The first five terms of the sequence are

- \(t_1=\dfrac{1}{1^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{5}\)

- \(t_2=\dfrac{1}{2^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{8}\)

- \(t_3=\dfrac{1}{3^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{13}\)

- \(t_4=\dfrac{1}{4^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{20}\)

- \(t_5=\dfrac{1}{5^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{29}\)

We were able to calculate these values by simply substituting \(1\) in for \(n\) to find term one, \(2\) in for \(n\) to find term two, etc.

Example 1—Part B

Consider the sequence defined by \(t_n=\dfrac{1}{n^2+4}\).

Evaluate \(t_{10}\), \(t_{100}\), and \(t_{1000}\). Express your answers as fractions and as decimals.

Solution

To find the \(10^{th}\) term, we simply need to substitute \(n = 10\) into our formula for the sequence and we get

\[t_{10} = \dfrac{1}{10^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{104} \approx 0.0096\]

When we evaluate the \(100^{th}\) term, we see that we arrive at

\[t_{100} = \dfrac{1}{100^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{10\ 004} \approx 0.00009996\]

This \(1000^{th}\) term looks similar to the \(100^{th}\) and \(10^{th}\) term. In this case, we have

\[t_{1000} =\dfrac{1}{1000^2+4}=\dfrac{1}{1\ 000\ 004} \approx 0.000000999996\]

What can you predict about the term value as \(n\) gets larger and larger and larger?

Example 1—Part C

Using your answers from part b, predict the value of \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty} \dfrac{1}{n^2+4}\).

Solution

In this example, we see that as \(n \to \infty\), the sequence \(t_n\) appears to approach the single value \(0\).

So if we were asked to evaluate the limit as \(n\) approaches infinity, we can justify saying that \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty}\dfrac{1}{n^2+4}=0\) by noting that we can make \(\dfrac{1}{n^2+4}\) as near as we like to \(0\) by making \(n\) sufficiently large.

I like to use this story in my class when I'm trying to explain this point. If you had a birthday party and you had one cake at your birthday party and we invited a very large crowd to come to your birthday, and every person at your party was given the same amount of cake, how much cake would each person get?

Well, if an entire stadium of people showed up to your birthday party and you only had one cake, the guests at your party would essentially receive no cake. The amount they would receive would be very, very small. Your guests would probably say that they received no cake at your party.

Sequences that approach a single finite value are called convergent. Because as \(n\) grows very, very large, the term value of the sequence approaches a particular value. In this case, it's approaching \(0\).

Example 2—Part A

Let's now try another example. I'll let you try this example on your own and then we'll take up its solution.

Consider the sequence defined by \(t_n=\dfrac{n-3}{n}\).

List the first five terms of this sequence.

Solution

The first five terms of the sequence are

- \(t_1=\dfrac{1-3}{1}=-2\)

- \(t_1=\dfrac{2-3}{2}=-\dfrac{1}{2}\)

- \(t_1=\dfrac{3-3}{3}=0\)

- \(t_1=\dfrac{4-3}{4}=\dfrac{1}{4}\)

- \(t_1=\dfrac{5-3}{5}=\dfrac{2}{5}\)

It is not obvious by looking at the first five terms of the sequence whether this sequence will be convergent or not.

Example 2—Part B

Consider the sequence defined by \(t_n=\dfrac{n-3}{n}\).

Evaluate \(t_{10}\), \(t_{100}\) and \(t_{1000}\). Express your answers as fractions and as decimals.

Solution

If we look at larger values, the \(10^{th}\) term, the \(100^{th}\) term, or the thousandth term, we start to see a pattern in the sequence.

\[t_{10} = \dfrac{10-3}{10}=\dfrac{7}{10} = 0.7\]\[t_{100} = \dfrac{100-3}{100}=\dfrac{97}{100} = 0.97\]\[t_{1000}=\dfrac{1000-3}{1000}=\dfrac{997}{1000} = 0.997\]

Example 2—Part C

Using your answers from part b, predict the value of \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty} \dfrac{n-3}{n}\).

Solution

Thus, it appears as though \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty}\dfrac{n-3}{n}\) is approaching the value \(1\).

To understand why this occurs, let's rewrite the expression \(\dfrac{n-3}{n}=1-\dfrac{3}{n}\). As \(n\) grows in size and becomes larger and larger, \(3\) divided by a very large number is roughly \(0\). Since \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty}\dfrac{3}{n}=0\), essentially, we have \(1 - \displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty}\dfrac{3}{n} = 1 - 0\), and so the sequence \(t_n\) has limit \(1\).

Example 3—Part A

Not all sequences are convergent. I'd like you to try the following example. Again, you're going to list the first five terms of the sequence. Then I would like you to graph these values.

Consider the sequence defined by \(t_n=\left(\dfrac{1-n}{n}\right)^n\).

List the first five terms of this sequence.

Solution

The first five terms of the sequence are

- \(t_1=\left(\dfrac{1-1}{1}\right)^1=0\)

- \(t_2=\left(\dfrac{1-2}{2}\right)^2=\dfrac{1}{4}\)

- \(t_3=\left(\dfrac{1-3}{3}\right)^3=-\dfrac{8}{27}\)

- \(t_4=\left(\dfrac{1-4}{4}\right)^4=\dfrac{81}{256}\)

- \(t_5=\left(\dfrac{1-5}{5}\right)^5=-\dfrac{1024}{3125}\)

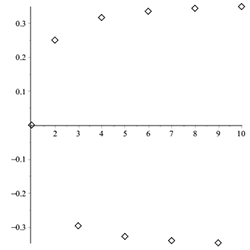

Example 3—Part B

Graph these values from part a.

Solution

When we graph these nine values, we see two parts of the graph emerging. We see a part of the graph that has positive values of \(y\), and we see a part of the graph with negative values of \(y\). Each time we go up a term number, we switch from a positive term value to a negative term value. This continues to oscillate back and forth as \(n\) becomes larger and larger. In this case, we are not approaching a single value.

Example 3—Part C

Using your answers from part b, predict the value of \(\displaystyle\lim_{n \to \infty} \left(\dfrac{1-n}{n}\right)^n\).

Solution

As we see from the graph, the values of this sequence alternate between positive values and negative values.

This sequence is not approaching a single finite value as \(n \to \infty\).

Since a single value is not approached, we say that the limit does not exist and that the sequence is divergent. So,

\[\lim_{n \to \infty} \left(\frac{1-n}{n}\right)^n \text{ does not exist.}\]

Lesson Part 3

Connecting Limits at Infinity with Horizontal Asymptotes

Limits at infinity have very important real life applications, especially when we're talking about curve sketching.

Horizontal asymptotes affect the end behaviour of a graph.

The end behaviour can be studied by considering very large positive and negative values of \(x\) and their corresponding value of \(f(x)\).

As we consider larger and larger positive values of \(x\), we say that \(x\) approaches positive \(\infty\), denoted as \(x \to +\infty\).

As we consider larger and larger negative values of \(x\), we say that \(x\) approaches negative \(\infty\), denoted as \(x \to -\infty\).

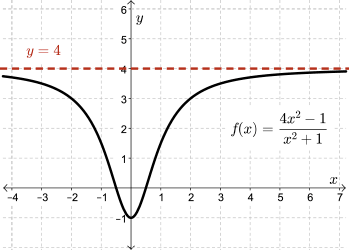

Example 4

Let's consider the graph of the function \(f(x)=\dfrac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}\).

We see that as \(x \to +\infty\), and as \(x \to -\infty\), \(f(x) \to 4\). This is sort of similar to what we've seen in sequences.

How can we use the algebraic representation of the function to determine this horizontal asymptote?

Solution

Well, remember when we were talking about sequences and we had the value \(1\) divided by a very large value of \(n\)? We notice that the value of this quotient approaches \(0\).

Consider \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to \infty}\dfrac{1}{x^n}\) for any positive number \(n\).

As \(x \to \infty\), the denominator here gets very, very large so \(\dfrac{1}{x^n} \to 0\).

This is a very special limit, which we will use to determine horizontal asymptotes.

To find the horizontal asymptote of \(f(x)=\dfrac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}\), if we were to simply think of directly substituting infinity into the numerator and denominator, we would have an expression involving infinity in both, which doesn't allow us to make many conclusions. Instead begin by identifying the highest power of \(x\) within this function and divide each term by this power.

Why are we going to do this? Well, once you divide each term in the numerator and each term in the denominator by that highest power of \(x\) and then simplify each of those individual fractions, you will see the idea of a constant divided by a power of \(x\), which we know the value is essentially \(0\). We can then evaluate this expression.

I'll show you what I mean by this by actually revealing to you the algebra. Ok, so we're asked to find the limit as \(x\) approaches infinity for the expression \(f(x)=\dfrac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}\). Begin by identifying the highest power of \(x\) you see in the rational function. In this case, it's \(x^2\).

Now, let's divide each term in the numerator and each term in the denominator by \(x^2\).

\[\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}=\lim_{x \to \infty}\left ( \frac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}\right ) \left ( \dfrac{\frac{1}{x^2}}{\frac{1}{x^2}} \right )=\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{\frac{4x^2}{x^2}-\frac{1}{x^2}}{\frac{x^2}{x^2}+\frac{1}{x^2}}\]

Now, simplify each term. Once we have simplified, we now have

\[\lim_{x \to \infty}\frac{4-\frac{1}{x^2}}{1+\frac{1}{x^2}} (\text{for } x \neq 0)\]

Well, in our explorations of limits, we know that \(\dfrac{1}{x^2}\) is essentially \(0\) when \(x\) approaches infinity since \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to \infty}\dfrac{1}{x^n}=0\).

Substitute \(0\) for each of these terms and evaluate the limit.

\[\lim_{x\to \infty} \dfrac{4-\frac{1}{x^2}}{1+\frac{1}{x^2}} = \frac{4-0}{1+0}=4\]

This is a new method for finding the horizontal asymptote of a rational function. Note that since \(f(x)=\dfrac{4x^2-1}{x^2+1}\) is an even function, the limit is the same whether \(x \to +\infty\) or \(x \to -\infty\), so \(y=4\) is a horizontal asymptote in both cases. However, this is not always the case.

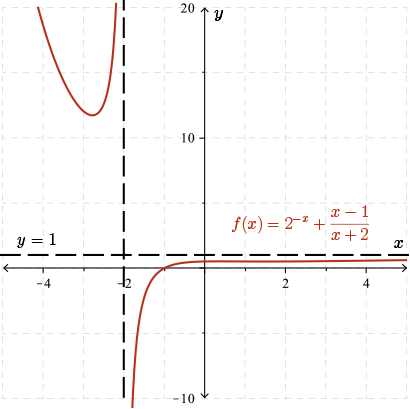

Example 5

Consider the graph of the function \(f(x)=2^{-x}+\dfrac{x-1}{x+2}\). A portion of its graph is shown. In this case, I'm not actually going to ask you to work through this example, we are just going to consider some of the properties of the function.

Image Description:

A graph of \(f(x)=2^{-x}+\dfrac{x-1}{x+2}\) is shown. The graph contains a horizontal asymptote at \(y = 1\), and a vertical asymptote at \(x = -2\). As \(x\) approaches positive infinity, \(f\) of \(x\) approaches the horizontal asymptote from below. As \(x\) approaches negative infinity, \(f\) of \(x\) approaches positive infinity.

Now since we can only see a finite portion of the graph, we cannot be sure of the limits as \(x\) approaches positive or negative infinity simply by looking at the graph. But it turns out that the end behavior of this function is exactly what is suggested in this graph. We note the following properties of the function \(f(x)\) (that are suggested by the given graph and can be verified algebraically):

As \(x\to \infty\), \(f(x) \to 1\).

Therefore, \(f(x)\) has a horizontal asymptote at \(y = 1\). However, as \(x \to -\infty\), \(f(x) \to \infty\).

Therefore, \(f(x)\) does not have a horizontal asymptote in the other direction.

It is not necessary that a function approach the same value as \(x\) approaches positive infinity and as \(x\) approaches negative infinity. Sometimes the limit as \(x\) approaches positive infinity is not equal to the limit as \(x\) approaches negative infinity. It depends on the function. In other words, a horizonal asymptote does not need to occur in both directions. That is, \(f(x)\) does not necessarily approach a horizontal asympotote as \(x\to +\infty\) and as \(x\to -\infty\).

Challenge Problem

Try this on your own and then click play to see the solution.

A rational function has a horizontal asymptote at \(y=\dfrac{1}{2}\) and the degree of its numerator and denominator is greater than or equal to \(1\). Determine a possible equation for this function.

Solution

In order for a rational function to have a non-zero horizontal asymptote, the degree of the numerator must be equal to the degree of the denominator.

Then, the rational function will have a horizontal asymptote at \(y=\dfrac{a}{b}\), where \(a\) and \(b\) are the coefficients of the highest degree term in the numerator and denominator, respectively.

For the function to have a horizontal asymptote at \(y=\dfrac{1}{2}\), the ratio of the leading coefficient of the numerator to the leading coefficient of the denominator must be \(\dfrac{1}{2}\).

One such function that satisfies these conditions is \(y=\dfrac{x+1}{2x}\).

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.