Lesson Part 1

Introduction

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) was a remarkable Swiss mathematician and physicist. He made massive contributions to mathematics, especially calculus, as well as physics, optics, magnetism, astronomy, and shipbuilding. Euler popularized the use of the symbol \(\pi\) and developed new approximations for it. He was the first to use the symbol \(i\) to represent imaginary numbers.

Euler also developed the irrational number \(e\), which is known as Euler's number and is defined as a limit:

\[e= \lim_{x\to \infty} \left ( 1 + \dfrac{1}{x} \right )^x \]

Euler's Number \(e\):

To better understand the value of this limit, let's examine some integer values of \(x\) to see the limiting value of this expression, which is the value of \(e\) approximated to a few decimal places.

| \(x\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{x}\right)^x\) |

| \(1\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{1}\right)^1=\left(\dfrac{2}{1}\right)^1=2\) |

| \(2\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^2=\left(\dfrac{3}{2}\right)^2=2.25\) |

| \(3\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{3}\right)^3=\left(\dfrac{4}{3}\right)^3\approx2.3704\) |

So we see that Euler's number is going to be just beyond the value \(2\). Now, let's choose some larger values for \(x\) so that we can see long into the future where \(x\) is a very large number; what is the value of \(e\)?

| \(x\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{x}\right)^x\) |

| \(100\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{100}\right)^{100}=\left(\dfrac{101}{100}\right)^{100}\approx2.7048\) |

| \(1000\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{1000}\right)^{1000}=\left(\dfrac{1001}{1000}\right)^{1000}\approx2.7169\) |

| \(10000\) |

\(y=\left(1+\dfrac{1}{10000}\right)^{10000}=\left(\dfrac{10001}{10000}\right)^{10000}\approx2.7181\) |

We see that as \(x\) becomes larger, the value of the expression changes by a smaller and smaller amount. In fact, the change can be shown to approach \(0\). In other words, the expression is approaching a limiting value. The limiting value of this expression is the irrational number \(e=2.718281828459\ldots\), a non-terminating decimal.

By making the substitution \(t=\dfrac{1}{x}\), we get the following alternate definition of Euler's number:

\[e = \lim_{x\to \infty}\left(1+\dfrac{1}{x}\right)^x=\lim_{t\to 0} (1+t)^{\frac{1}{t}}\]

Notice that if \(t=\dfrac{1}{x}\), then \(x=\dfrac{1}{t}\). And so the exponent becomes \(\dfrac{1}{t}\). Also, notice that if \(x\) approaches infinity, then \(t\), which is \(\dfrac{1}{x}\), must approach \(0\). Therefore, these two limits are equivalent. Some textbooks may use this second limit as the primary definition of the number \(e\).

Lesson Part 2

Exponential Functions with Base \(e\)

OK, so now that we know what Euler's number is, let's look at exponential functions with base \(e\).

Recall the graph of the basic exponential function \(y=2^x\). This expression

- has a horizontal asymptote in the line \(y=0\),

- has a \(y\)-intercept is \(1\),

- starts very close to the \(x\)-axis on the left side of the grid, and

- exponentially increases as we move towards the right.

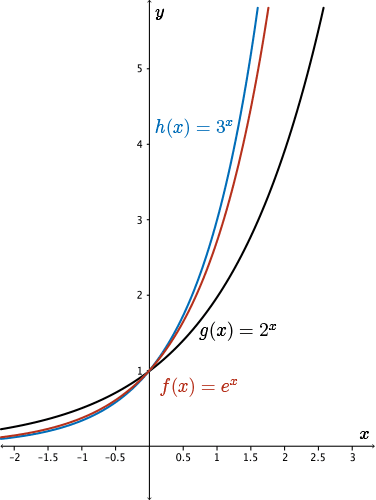

Since Euler's number is between \(2\) and \(3\), let's compare the graph of \(f(x)=e^x\) with the graphs of \(g(x)=2^x\) and \(h(x)=3^x\).

We see that these three functions are very similar in their behavior and that the graph of \(f(x)=e^x\) is in between the graphs of \(g(x)=2^x\), and \(h(x)=3^x\). Since \(e\) is roughly \(2.7\), of course, the graph of \(e^x\) will be slightly closer to the graph of \(3^x\).

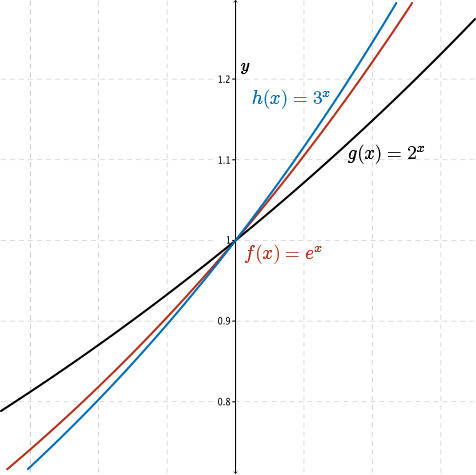

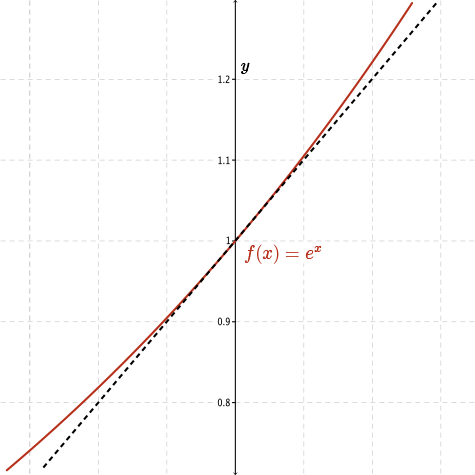

Now, let's zoom in on the graphs of \(2^x\), \(e^x\), and \(3^x\) when \(x=0\). Let's carefully examine the slope of the tangent to each of these graphs at \(x=0\).

It is worth noting that the slope of the tangent line to \(2^x\) is less than \(1\), while the slope of the tangent line to \(3^x\) is greater than \(1\).

When we look at the slope of the tangent for the exponential function with Euler's number \(e\) as its base, the slope of the tangent is exactly \(1\) at \(x=0\). Moreover, Euler's number, \(e\), is the base needed to make the exponential function have exactly slope \(1\) at \(x=0\). This is a very important property of an exponential function with base \(e\). We will use this definition of \(e\) when we discuss the derivative of the function \(f(x)=e^x\).

The Inverse of the Exponential Function, \(e^x\)

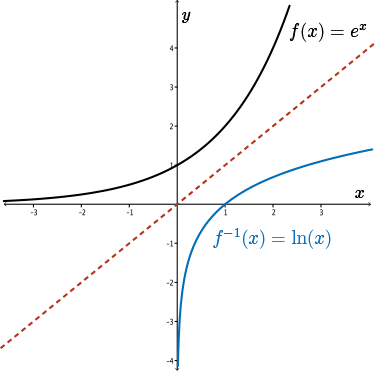

In previous mathematics courses, you learned that the inverse of an exponential function is the logarithmic function with the same base.

For example, the inverse of the exponential function \(f(x)=2^x\) is \(f^{-1} (x) = \log_2 (x)\).

The inverse of the exponential function \(g(x) = e^x\) is \(g^{-1} (x) = \log_{e} (x) = \ln (x)\).

Rather than using \(\log_e(x)\), mathematicians use \(\ln (x)\) to shorten this expression. \(\ln(x)\) stands for the natural logarithm of \(x\) and is pronounced “lawn \(x\).”

The Graphs of the Exponential Function \(y=e^x\) and the Logarithmic Function \(y=\ln(x)\)

In past mathematics courses, we also learned that the graph of an inverse function is the function reflected in the line \(y=x\). So here's the graph of \(\ln(x)\) on the coordinate plane.

Notice how we still see reflection in the line \(y=x\). Please pay special attention to the domain of \(\ln(x)\). The domain of \(\ln(x)\) is for all \(x\) greater than \(0\), whereas the domain for \(e^x\) is all real values of \(x\).

An exponential equation can be converted into a logarithmic equation. For example, if \(e^x =c\), where \(c\) is some positive constant, then \(x=\ln( c)\) (where \(\ln\) is \(\log\) base \(e\)).

Converting exponential equations into logarithmic equations can be very useful when solving equations. You will find \(\ln\) as a button on your scientific calculator.

The Derivative of the Exponential Function, \(e^x\)

Now that we have identified Euler's number, looked at the behavior of the curve \(y=e^x\), and looked at its inverse, \(\ln(x)\), what is the derivative of an exponential function with base \(e\)?

Let's investigate the slope of the tangent to many points along the curve of \(f(x)=e^x\) by using the following Maple investigation.

In this investigation, you will see the graph of \(f(x)=e^x\) and a tangent drawn at one point on the left side of the graph. Maple has calculated the slope of this tangent and then plotted the \(x\)-coordinate of the point of tangency with the value of the slope of the tangent at that point. This will give us the numerical values of the derivative of \(f(x)=e^x\). Now, as we drag this point from the left side to the right side of the grid, what I would like you to do is to look at the points plotted, identify how you would connect these points, and then see if you can determine what function is graphed by these points. If we were to connect these values, what function would you see?

Try it now.

Investigation

See the investigation in the side navigation.

Lesson Part 3

The Derivative of the Exponential Function, \(f(x)=e^x\)

From the investigation, we see that the slope of the tangent to the curve is equal to the \(y\)-value at each point of tangency. What does this tell us?

This tells us that for \(f(x)=e^x\), \(f'(x)=e^x\) as well. Using the definition of the derivative to differentiate the function \(f(x)=e^x\) leads to another interesting limit.

Recall the definition of the derivative:

\[\dfrac{dy}{dx}= \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\]

When we substitute \(f(x+h)\) and \(f(x)\) into this formula, we have:

\[\dfrac{dy}{dx}= \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^{x+h}-e^x}{h}\]

Well, in the numerator we have two terms. What is common to both of these two terms is \(e^x\). Recall the exponent law when multiplying powers of the same base. In this case, we add the exponents. So \(e^{x+h}\) can also be written as \(e^x e^h\), giving:

\[\lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^{x+h}-e^x}{h}= \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^x e^h-e^x}{h}\]

When we look at the two terms in the numerator, we notice that there is a common factor of \(e^x\) in both terms. Let's remove this common factor:

\[\lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^x e^h-e^x}{h}= \lim_{h \to 0} \left[e^x\left(\dfrac{e^h-1}{h}\right)\right]\]

Using our limit properties, we can distribute the limit as \(h\) approaches \(0\) to each part of the product:

\[\lim_{h \to 0} \left[e^x\left(\dfrac{e^h-1}{h}\right)\right]= \left(\lim_{h \to 0} e^x \right) \left( \lim_{h\to 0}\dfrac{e^h-1}{h}\right)\]

Recall that Euler's number, \(e\), is the base needed to make an exponential function have slope exactly \(1\) at \(x=0\).

Therefore, the value of the limit \(\displaystyle \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^h -1}{h}\) must be \(1\) by this definition of \(e\), since this limit is exactly the definition of the derivative of \(e^x\) at \(0\). You may study this limit in future mathematics courses.

\[\lim_{h \to 0} e^x\left[\dfrac{e^h-1}{h}\right] = \left ( \lim_{h\to 0} e^x \right ) \underbrace{\left ( \lim_{h\to 0} \dfrac{e^h -1}{h} \right ) }_{=1}\]

Also, since \(e^x\) does not depend on \(h\), we know that:

\[ \left ( \lim_{h\to 0} e^x \right ) = e^x\]

Thus:

\[\begin{align*} \left ( \lim_{h\to 0} e^x \right ) \underbrace{\left ( \lim_{h\to 0} \dfrac{e^h -1}{h} \right ) }_{=1} &= (e^x)(1) \\ &=e^x\end{align*}\]

Therefore, \(e^x\) has the remarkable property that

\[\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big ( e^x \Big ) = e^x\]

The Derivative of the Exponential Function \(f(x)=e^x\)

If \(f(x)=e^x\), then \(f'(x)=e^x\) for all real \(x\).

Examples

So, now that we know the derivative of \(f(x)=e^x\), let's put this new rule to work and try some examples.

Example 1

Differentiate \(y=e^{4x}\).

Solution

When we look at this function, we see that \(y=e^{4x}\) is a composite function. The inner function is \(g(x)=4x\), while the outer function is \(h(x)=e^x\). To differentiate this function, we must use the chain rule, since it is a composite function.

We begin by letting the inner function be \(u=4x\), which then means that our outer function is \(y=e^u\).

Now, recall the definition for the chain rule. The chain rule tells us:

\[\dfrac{dy}{dx} = \left ( \dfrac{dy}{du} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{du}{dx} \right )\]

So, we look at the function \(y=e^u\) and differentiate this function to determine \(\dfrac{dy}{du}\). Well, the derivative of \(e^u\) with respect to \(u\) is, of course, \(e^u\). We saw that previously.

Now we need \(\dfrac{du}{dx}\). Well, since \(u=4x\), \(\dfrac{du}{dx}=4\).

So, the derivative of our function is:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \left ( \dfrac{dy}{du} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{du}{dx} \right )\\ &=\left(e^u\right)\left(4\right)\\ &=4e^{4x} \end{align*}\]

Please take note: we do not use the power rule to differentiate exponential functions.

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 2

Let's try another example. Differentiate \(f(x)=x^5e^{-3x^2}\).

Solution

Notice how I said “times” in the middle of this function.The function \(f(x)=x^5e^{-3x^2}\) is a product of the \(2\) functions \(g(x)=x^5\) and \(h(x)=e^{-3x^2}\). Therefore, to differentiate this function, we must use the product rule. Also, the function \(h(x)=e^{-3x^2}\) is a composite function, so to differentiate this function, we must use the chain rule.

Let's begin by differentiating \(h(x)=e^{-3x^2}\).

We will let the inner function be \(u=-3x^2\), which means that the outer function is \(y=e^u\). Then:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \left ( \dfrac{dy}{du} \right ) \left ( \dfrac{du}{dx} \right )\\ &=\left(e^u\right)\left(-6x\right)\\ &=-6xe^{-3x^2} \end{align*}\]

So \(h'(x)=-6xe^{-3x^2}\)

Now let's differentiate the entire function, \(f(x)=x^5 e^{-3x^2}\). Well, the product rule tells us:

\[f'(x) = g'(x)h(x)+g(x)h'(x)\]

So:

\[\begin{align*} f'(x) &= \left(5x^4\right)\left(e^{-3x^2}\right) + \left(x^5\right)\left(-6xe^{-3x^2}\right)& \text{differentiate }g(x) \text{ and }h(x)\\ &= 5x^4e^{-3x^2} - 6x^6e^{-3x^2} & \text{simplifying}\\ &=x^4e^{-3x^2}\left(5-6x^2\right) &\text{remove common factors} \end{align*}\]

Special Note: It is important to factor the derivative as much as possible, as this will help when sketching the graph of the function or determining its properties.

Lesson Part 5

Examples

Example 3

Differentiate \(y=e^x(e^{4x})\). First, try this on your own, then compare your answer with the solution.

Solution

There are two methods for differentiating this expression.

Method 1

In this method, we could differentiate \( y \) by using the product rule and chain rule, much like we did in the previous examples. So since we have a product of \(e^x\) times \(e^{4x}\), we know that to differentiate this expression we must use the product rule:

\[\dfrac{dy}{dx}=e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)+e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)(4)\]

Remember, we did a very similar derivative of \(e^{4x}\) in example \(1\). It is in this case that we use the chain rule. Now we can simplify this expression. Look at the powers of \(e\): we have \(e^x\) and \(e^{4x}\) in both terms. The first term has constant multiple \(1\), and the second term has constant multiple \(4\). So altogether, we have:

\[e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)+e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)(4)=5e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)\]

Well, we know how to multiply powers with the same base. We do that by adding exponents. So this simplifies to:

\[5e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)=5e^{5x}\]

Moreover:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx}&=e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)+e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)(4)\\ &=5e^x\left(e^{4x}\right)\\ &=5e^{5x} \end{align*}\]

Method 2

There is another method though of differentiating this expression. We could have simplified the expression of \(y\) first by applying the exponent rules. So rather than differentiating \(y\) as a product, we could instead multiply \(e^x\) and \(e^{4x}\) using our exponent rules, which simplifies to:

\[\begin{align*} y&=e^x(e^{4x}) \\ &= e^{x+4x} \\ &=e^{5x} \end{align*}\]

Now, let's differentiate this function using the chain rule:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= (e^{5x})(5) \\ &=5e^{5x} \end{align*}\]

So before you differentiate an expression with exponential functions, always check to see if you can apply the exponent rules. This may help you differentiate the expression.

Lesson Part 6

Examples

Now that we have explored three different examples, let's try a more challenging question.

Challenge Question

Show that \(e^{2x}+4e^{-4x} \gt 2\) for all \(x\).

Solution

So how will we do this? To prove that \(e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\gt 2\), we show that the minimum value of \(e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\) is greater than \(2\).

Let's start by letting \(y=e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\).

First note that the domain of the function is \(x\in\mathbb{R}\). This is because each exponential term is defined for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}\). We also note that each of the exponentials \(e^{2x}\) and \(4e^{-4x}\) are continuous and differentiable for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}\) and so \(y=e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\) is a continuous and differentiable function. Therefore, if the function has an absolute minimum, then it must occur at local extreme where \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}=0\).

At this point, it is not absolutely clear that this function even has a minimum value, but if it does, then it must occur where the function has a local minimum. So let's go in search of that local minimum. Differentiating \(y=e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\) we get:

\[\begin{align*} \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= 2e^{2x}-16e^{-4x} \end{align*}\]

Since the minimum value will occur when \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}=0\), let's substitute \(0\) in for \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) and solve for \(x\):

\[0= 2e^{2x}-16e^{-4x}\]

When we look at these two terms, we see that \(2\) is common to both. Let's remove it:

\[2e^{2x}-16e^{-4x}=2\left(e^{2x}-8e^{-4x}\right)\]

What power, with base \(e\), is common to both of these terms? Well, if we had \(x^5\) and \(x^3\), I think you would agree with me that we take the smaller of the two exponents as common to both terms. This applies here. So, when we look at \(e^{2x}\) and \(e^{-4x}\), \(-4x\) is the smaller exponent on base \(e\). So we can remove that smaller power from both terms:

\[2\left(e^{2x}-8e^{-4x}\right)= 2e^{-4x}\left[e^{6x}-8\right]\]

In summary:

\[\begin{align*} 0&=2e^{2x}-16e^{-4x}\\ 0&=2\left(e^{2x}-8e^{-4x}\right)\\ 0&=2e^{-4x}\left[e^{6x}-8\right] \end{align*}\]

Therefore, either \(e^{-4x}=0\) or \(e^{6x}-8=0\).

But we've already looked at the graph at \(e^x\) and we know that \(e^{-4x}>0\) for all \(x\in\mathbb{R}\). Remember, it had a horizontal asymptote in the line \(y=0\). Thus, we need

\[\begin{align*} e^{6x}-8&=0\\ e^{6x}&=8 &\text{adding } 8 \text{ to both sides}\\ 6x&=\ln(8) & \text{convert to logarithmic form}\\ x&=\frac{1}{6}\ln(8)&\text{multiply by } \frac{1}{6}\\ x&\approx 0.347 \end{align*}\]

So we now know where the minimum value exists. Let's find the actual minimum value of the expression. To determine the minimum value, let \(x=\dfrac{1}{6}\ln(8)\) in the equation \(y=e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\):

\[\begin{align*} y&=e^{2\left(\frac{1}{6}\ln(8)\right)}+4e^{-4\left(\frac{1}{6}\ln(8)\right)}\\ &=e^{\left(\frac{1}{3} \ln(8) \right)}+4e^{\left(-\frac{2}{3}\ln(8)\right)}\\ \end{align*}\]

Note that each exponent has a product. The first exponent is the product of \(\dfrac{1}{3}\ln(8)\), and the second exponent is a product \(-\dfrac{2}{3}\ln(8)\). Well, when we multiply exponents together (this comes from the exponent law where we have a power raised to an exponent). So instead of having a product within each exponent, we could write:

\[y=\left(e^{\ln(8)}\right)^\frac{1}{3}+4\left(e^{\ln(8)}\right)^{-\frac{2}{3}}\]

Recall that \(a^{\log_{a}(b)}=b\). (In other words, if you have an exponential function that is raised to an exponent of a logarithm with same base, then the inner part of the logarithm is equal to this entire exponential function.) So how does that connect to what we've been doing? Well, we have the expression, \(e^{\ln(8)}\), so \(e^{\ln(8)}=e^{\log_{e}(8)}=8\). Thus,

\[\begin{align*} y&=8^{\frac{1}{3}}+4(8)^{-\frac{2}{3}}\\ &=2+ \dfrac{4}{\left( 8^\frac{1}{3}\right)^2}\\ &=3 \end{align*}\]

Since the minimum value of \(y=e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\) is \(3\), then \(e^{2x}+4e^{-4x}\gt 2\) for all \(x\).

Quiz

See the quiz in the side navigation.