Lesson Part 1

In This Unit

- We will explore some applications of the derivatives of exponential, logarithmic, and trigonometric functions.

- We will revisit familiar topics including rates of change, curve sketching, optimization, and related rates. This time, we will have a larger repertoire of functions to work with.

We will start our discussion with the topic of rates of change.

In This Module

We have already seen how calculus, more specifically the derivative, can be used in the sciences to study rates of change of physical quantities.

- We will explore such applications, where the modelling equations involve exponential, logarithmic, and trigonometric functions.

Examples

Example 1—Part A

A population of algae in a small pond grows as the organisms reproduce. The population of algae after \(t\) hours is modelled by the equation \(P(t) = 150e^{2t}\).

What is the initial population of algae (at \(t=0\))?

Solution

We must find \(P(0)\). Substituting \(0\) into our equation for the population, we get

\[\begin{align*}P(0) & = 150 e^{2(0)} \\ & = 150 e^{0} \\ & = 150(1) \\ & = 150 \end{align*}\]

Therefore, the initial population of algae is \(150\).

Example 1—Part B

A population of algae in a small pond grows as the organisms reproduce. The population of algae after \(t\) hours is modelled by the equation \(P(t) = 150e^{2t}\).

At what rate is the population changing after \(30\) mins?

Solution

Here, we're asked to find the instantaneous rate of change of the function \(P(t)\) at the time \(t = 30\) mins.

The instantaneous rate of change of the population is found by differentiating the population function, \(P(t)\), with respect to time.

\(P(t) = 150e^{2t}\) is a composite function with inner function \(u = 2t\) and outer function \(P(u) = 150e^{u}\).

To differentiate, we must use the known derivative of the exponential function along with the chain rule.

By the chain rule,

\[\dfrac{dP}{dt}=\left(\dfrac{dP}{du}\right)\left(\dfrac{du}{dt}\right)\]

Next, we substitute the function \(P\) in terms of \(u\) and the function \(u\) in terms of \(t\) into our expression.

\[\dfrac{dP}{dt}=\dfrac{d}{du}\Big(\textcolor{NavyBlue}{150 e^{u}}\Big)\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(\textcolor{BrickRed}{2t}\Big)\]

Since \(\dfrac{d}{du}e^u=e^u\), the first derivative is just \(150 e^u\). The second derivative with respect to \(t\) is \(2\).

\[\begin{align*}\dfrac{dP}{dt}&=150 e^{u} (2)\\ &=300 e^{2t}\end{align*}\]

Therefore, we get a final answer of \(300 e^{2t}\) once we substitute \(u=2t\) at the end. So this gives us an expression for the instantaneous rate of change of the population at any time \(t\).

We want the rate of change after \(30\) mins, or \(0.5\) hours, and so we calculate the rate of change at \(t=0.5\).

\[P'(0.5) = 300e^{2(0.5)} = 300 e^{1} = 300 e \approx 815.48\]

Therefore, the population is growing at a rate of approximately \(815\) organisms per hour at \(t = 30\) mins.

Example 1—Part C

A population of algae in a small pond grows as the organisms reproduce. The population of algae after \(t\) hours is modelled by the equation \(P(t) = 150e^{2t}\).

When was the population of algae increasing at a rate of \(600\) organisms per hour? Answer to the nearest minute.

Solution

Here, we must find the value of \(t\) such that \(P'(t) = 600\).

So starting with the formula of the derivative, we substitute our value of \(600\) for the derivative on the left hand side and solve for \(t\).

\[\begin{align*} P'(t) & = 300 e^{2t} \\ 600 & = 300 e^{2t} \\ 2 & = e^{2t} \\ \ln(2) & = \ln\left(e^{2t}\right) & \text{taking the natural }\log\text{ of both sides} \\ \ln(2) & = 2t & \text{since }\ln(e^{x}) = x \\ t & = \dfrac{\ln(2)}{2} \end{align*}\]

Now the question is asking us to answer to the nearest minute. Since \(t\) is given an hours, we're going to need to convert to minutes.

As \(t= \dfrac{\ln(2)}{2} \approx 0.347\) h, the population is growing at a rate of \(600\) organisms per hour when \(t \approx (0.347)(60) \approx 21\) mins.

Lesson Part 2

Examples

Example 2—Part A

The mass, \(m\), in milligrams, that remains of a radioactive substance after \(t\) years is given by the equation \(m(t) = 15a^{-\frac{t}{10}}\) for some positive constant \(a\). After \(10\) years, exactly half of the initial sample remains.

What is the value of the constant \(a\)?

Solution

We need to use the information given in the question to solve for this number \(a\).

We are given the equation \(m(t) = 15 a^{-\frac{t}{10}}\), which represents the mass of the substance at time \(t\). We are also given that at \(t=10\), exactly half of the sample remains.

If we compute the mass at time \(0\), we can find the mass of the initial substance.

Substituting \(0\) into our expression for \(m(t)\), we get \(m(0) = 15 a^{0} = 15\). Therefore, the sample started out with a mass of exactly \(15\) mg. At \(t = 10\), exactly half of the mass remained, and so the sample's mass was \(\frac{1}{2}15\) mg.

Using this data point, we can get the following equation:

\[m(10) = 15 a^{-\frac{10}{10}} = \frac{1}{2}(15)\]

Solving for \(a\), we first note that \(a^{-\frac{10}{10}} = a^{-1}\).

\[15a^{-1}=\dfrac{1}{2}(15)\]

Dividing through by \(15\) gives us

\[a^{-1}= \dfrac{1}{2}\]

\(\frac{1}{2}\) is just \(2^{-1}\).

\[a^{-1}=2^{-1}\]\[a=2\]

And so we see that \(a = 2\).

Example 2—Part B

The mass, \(m\), in milligrams, that remains of a radioactive substance after \(t\) years is given by the equation \(m(t) = 15a^{-\frac{t}{10}}\) for some positive constant \(a\). After \(10\) years, exactly half of the initial sample remains.

At what rate is the sample decaying after \(35\) years?

Solution

So this question is asking about the instantaneous rate of change of the mass of the substance. So this tells us that we need to first compute the derivative of the function \(M(t)\).

From part a, we have \(m(t) = 15(2)^{-\frac{t}{10}}\) and so, we can find this derivative using the chain rule and the derivative for the exponential function of base \(2\).

\[m'(t) = 15 [\ln(2)] ~(2)^{-\frac{t}{10}} \dfrac{d}{dt} \left(-\dfrac{t}{10} \right)\]

Well, the constant 15 is left unchanged. The derivative of the exponential of base \(2\) is equal to the exponential times \(\ln(2)\). And by the chain rule, we need to multiply by the derivative of the inner function, \(-\frac{t}{10}\), which is the fraction \(-\frac{1}{10}\).

\[\begin{align*}m'(t) & = 15 [\ln(2)] ~(2)^{-\frac{t}{10}} \left(-\dfrac{1}{10} \right)\\ & = -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} ~(2)^{-\frac{t}{10}}\end{align*}\]

The question is asking for the rate of change when \(t=35\) years. So we calculate the derivative at \(t=35\).

\[\begin{align*} m'(35)&= -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} ~(2)^{-\frac{35}{10}} \\ &= -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} ~(2)^{-3.5} \end{align*}\]

Since we have a power of \(2\) in the numerator and the denominator, we'll combine it using the exponential rule for a quotient.

\[\begin{align*} m'(35) & = -3 \left [\ln(2) \right ] (2)^{-3.5 - 1} \\ & = -3 \left [ \ln(2) \right ] (2)^{-4.5}\end{align*}\]

When we evaluate this expression and round to three decimal places, we get

\[m'(35) \approx -0.092\]

Now, the negative in the derivative signifies the sample is decaying. In other words, it is losing mass.

Therefore, the sample is decaying at a rate of approximately \(0.092\) mg per year at \(t = 35\) years.

Example 2—Part C

The mass, \(m\), in milligrams, that remains of a radioactive substance after \(t\) years is given by the equation \(m(t) = 15a^{-\frac{t}{10}}\) for some positive constant \(a\). After \(10\) years, exactly half of the initial sample remains.

At what time \(t \geq 0\) is the sample decaying at the fastest rate? What is this rate?

Solution

If we look at the derivative that we found in part b, we see that we have an exponential function times a negative constant. Since an exponential function is always positive, \(m'(t)\lt 0\) for all \(t\).

\[m'(t)= -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} ~(2)^{-\frac{t}{10}}\]

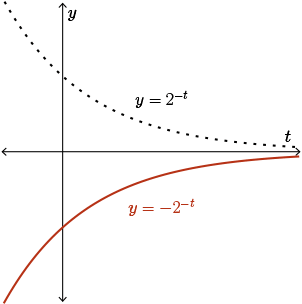

We're looking for when the sample is decaying at the fastest rate. In other words, when we have the steepest negative slope. So we are looking for the minimum value of \(m'(t)\) on \(t \geq 0\). We will find this minimum value by looking at the shape of the function \(m'(t)\). Recall the shapes of the graphs \(y = 2^{-t}\) and \(y = -2^{-t}\).

Image description: \(y = 2^{-t}\) is always positive, but continuously slopes downward, approaching \(0\) as \(t\) grows larger. \(y = -2^{-t}\) is always negative, but continuously slopes upward, approaching \(0\) as \(t\) grows larger.

\(y = 2^{-t}\) is the decaying exponential function. So of course, the function \(y = -2^{-t}\) is this function reflected in the \(x\)-axis.

Observe that, on the interval \(t \geq 0\), the function \(y = -2^{-t}\) attains its extreme value at \(t=0\).

Since \(m'(t) = -c(2)^{-kt}\), for \(c\), \(k \gt 0\), the graph of \(m'(t)\) has the same shape, but it is scaled in the horizontal and vertical direction.

It follows that \(m'(t)\) also attains its extreme value at \(t=0\).

Therefore, the sample is decaying at the fastest rate when \(t=0\) and this rate is

\[m'(0) = -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} ~(2)^{0} = -\dfrac{3 \ln(2)}{2} \approx -1.04 \text{mg per year}\]

Again, the negative sign in the derivative signifies that mass is being lost.

Lesson Part 3

Examples

Example 3—Part A

After a plane takes off, its altitude, measured in feet, is given by the equation

\[A(t) = 1000 \ln(t+1)\]

where \(t\) is measured in minutes.

Sketch the graph of the altitude function for \(t \geq 0\).

Solution

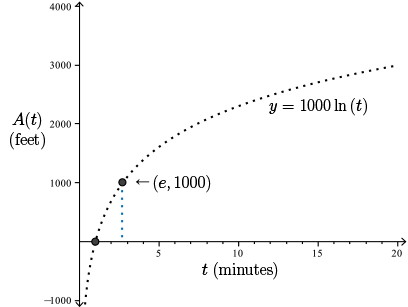

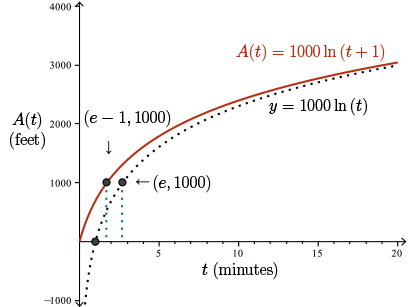

First we draw a rough sketch of the function, \(1000 \ln(t)\). This has \(x\)-intercept \(t = 1\), because \(\ln(1) = 0\). And we also find that \(1000 \ln (e) = 1000\), and so we can plot a second point.

Our function, \(A(t)\), is just the previous function shifted one unit to the left. So we get the function \(A(t)\) on the interval, \(t \geq 0\). This picture is reasonable for the physical situation, because we have a steep climb at the start of the trip that levels off as time goes on.

Example 3—Part B

After a plane takes off, its altitude, measured in feet, is given by the equation

\[A(t) = 1000 \ln(t+1)\]

where \(t\) is measured in minutes.

At what rate is the plane climbing after \(4\) minutes?

Solution

Here we need the instantaneous rate of change of the function \(A(t)\) at \(t = 4\). So first we need to compute the derivative.

Since \(\dfrac{d}{du}\Big(\ln{(u)}\Big) = \dfrac{1}{u}\), we have

\[\begin{align*} A'(t) & = 1000 \left (\dfrac{1}{t+1} \right )\dfrac{d}{dt}\Big(t+1\Big) & \text{by the chain rule} \\ & = 1000 \left (\dfrac{1}{t+1} \right )(1) \\ & = \dfrac{1000}{t+1} \end{align*}\]

To find the rate of climb after \(4\) minutes, we calculate \(A'(4)\):

\[A'(4) = \dfrac{1000}{4+1} = \dfrac{1000}{5} = 200 \text{ feet per minute}\]

Example 3—Part C

After a plane takes off, its altitude, measured in feet, is given by the equation

\[A(t) = 1000 \ln(t+1)\]

where \(t\) is measured in minutes.

When is the plane climbing at a rate of less than \(8\) feet per minute?

Solution

Recall that \(A'(t)=\dfrac{1000}{t+1}\) is a decreasing function.

So if at some time \(t_1\) we reach a value of \(A'(t_1) = 8\), then we must have \(A'(t) \leq 8\) for all \(t \geq t_{1}\).

To find this bound, we will solve the equation \(A'(t) = 8\).

\[\begin{align*} A'(t) = \dfrac{1000}{t+1} & = 8 \\ 1000 & = 8(t+1) \\ 125 & = t+1 \\ t & = 124 \end{align*}\]

Since \(A'(t) = \dfrac{1000}{t+1}\) is a decreasing function and \(A'(124) = 8\), we have \(A'(t) \leq 8\) for all \(t \geq 124\), so we let \(t_{1} = 124\) minutes.

Lesson Part 4

Examples

Example 4—Part A

Water is flowing in and out of a reservoir tank. The volume of water, in litres, in the tank at time \(t\), in hours, is modelled by the equation \(V(t) = 100 \cos(\pi t) + 150\).

Find an expression for the instantaneous rate of change of the volume of water in the tank at time \(t\).

Solution

Since we know the cosine function oscillates, the volume of water in this reservoir tank will also oscillate.

The volume function \(V(t)\) is a composite function and so we use the chain rule to find \(V'(t)\).

The inner function is \(u=\pi t\) and the outer function is \(V(u) = 100 \cos(u) + 150\). Recall that \(\dfrac{d}{du}(\cos(u))=-\sin(u)\), so we have

\[\begin{align*} V'(t) & = \left[100 (-\sin(\pi t)) \right] \left(\frac{d}{dt}\Big(\pi t\Big)\right), &\text{by the chain rule}\\ & = \left[100 (-\sin(\pi t)) \right] (\pi) \\ & = -100\pi \sin(\pi t) \end{align*}\]

This gives us an expression for the instantaneous rate of change at any time \(t\).

Example 4—Part B

Water is flowing in and out of a reservoir tank. The volume of water, in litres, in the tank at time \(t\), in hours, is modelled by the equation \(V(t) = 100 \cos(\pi t) + 150\).

At what rate is the volume of water changing after \(10\) minutes?

Solution

We want the value of \(V'(t)\) when \(t = 10\) mins or, equivalently, when \(t = \frac{1}{6}\) h.

\[V'\left(\frac{1}{6}\right) = -100\pi \sin\left(\frac{\pi}{6}\right)\]

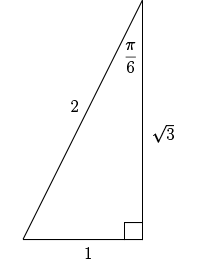

So to find the value, we first need to figure out what \(\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right)\) is.

From the \( 1 \text{-} 2 \text{-} \sqrt{3} \) or \( \dfrac{\pi}{6} \text{-} \dfrac{\pi}{3} \text{-} \dfrac{\pi}{2} \) triangle, we have \( \sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{6}\right) =\dfrac{1}{2} \), so

\[V'\left(\frac{1}{6}\right) = -100 \pi \left(\frac{1}{2}\right) = -50 \pi\]

Again, this negative sign means the water is flowing out of the tank at \(t = \dfrac{1}{6}\).

Therefore, the tank is losing water at a rate of \(50 \pi\) litres per hour at \(t = 10\) minutes.

Example 4—Part C

Water is flowing in and out of a reservoir tank. The volume of water, in litres, in the tank at time \(t\), in hours, is modelled by the equation \(V(t) = 100 \cos(\pi t) + 150\).

At what times \(t \geq 0\) is the instantaneous rate of change of the volume of water equal to \(0\)? In other words, at what time is there no water flowing either out or in?

Solution

We want \(t \geq 0\) such that \(V'(t) = 0\).

Using our expression for the derivative, this amounts to solving the equation \(-100\pi \sin(\pi t) = 0\).

We know that \(\sin(x)=0\) when \(x = 0, \pi, 2\pi, 3\pi, \ldots\) or \(\sin(x)=0\) when \(x=k\pi\), \(k\in\mathbb{Z}\).

This occurs exactly when \(\sin(\pi t) = 0\), and we know that \( \sin(\pi t) = 0 \) when \( \pi t = k \pi , k \in \mathbb{Z} \), so it occurs when \(t\) is a non-negative integer.

This implies \(\sin(\pi t) = 0\) exactly when \(t\) is a non-negative integer.

So we conclude that the instantaneous rate of change is equal to \(0\) when \(t\) is any non-negative integer.

Example 4—Part D

Water is flowing in and out of a reservoir tank. The volume of water, in litres, in the tank at time \(t\), in hours, is modelled by the equation \(V(t) = 100 \cos(\pi t) + 150\).

At what times \(t\), satisfying \(1 \leq t \leq 2\), does the rate of change of the volume of water have a magnitude of \(\left(50 \sqrt{2} \right)\pi\) litres per hour?

Solution

This question is asking for a magnitude, and so the rate could be positive or negative.

Here we need to find \(t\) such that \(1 \leq t \leq 2\) and \(\lvert V'(t) \rvert = \left(50 \sqrt{2} \right)\pi\). We have

\[\lvert V'(t)\rvert = \lvert -100\pi \sin(\pi t)\rvert = 100 \pi~ \lvert \sin(\pi t) \rvert \]

and so \(\lvert V'(t)\rvert = \left(50 \sqrt{2} \right)\pi\) if

\[\left(50 \sqrt{2} \right)\pi = 100 \pi~ \lvert \sin(\pi t)\rvert\]

or

\[\lvert \sin(\pi t)\rvert = \frac{50 \sqrt{2} \pi}{100 \pi} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\]

From the \(1 \text{-} 1 \text{-} \sqrt{2}\) or \(\dfrac{\pi}{4} \text{-} \dfrac{\pi}{4} \text{-} \dfrac{\pi}{2}\) special triangle, we have \(\sin\left(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\right) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}} = \dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\).

So, the reference angle is \(\dfrac{\pi}{4}\).

We want \(t\) such that \(\lvert \sin(\pi t)\rvert = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\), so we want to find \(t\) such that \(\sin(\pi t) = \pm \dfrac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\). This occurs when

\[t = \dfrac{1}{4}, \ \dfrac{3}{4}, \ \dfrac{5}{4}, \ \dfrac{7}{4},\ \dfrac{9}{4}, \ldots\]

Since we are restricted to the interval \(1 \leq t \leq 2\), we have only \(2\) times that work: \(t = \dfrac{5}{4}\) and \(t = \dfrac{7}{4}\).

So, we conclude that the rate of change has a magnitude of \(\left(50 \sqrt{2} \right)\pi\) L per hour at \(t = 1.25\) hours and \(t = 1.75\) hours.

Lesson Part 5

Examples

Example 5

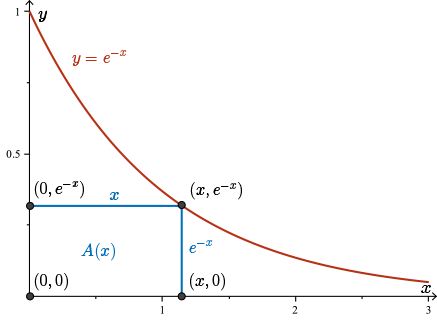

Consider the graph of \(y = e^{-x}\) for \(x \geq 0\).

There are infinitely many rectangles having vertices arranged as follows: one vertex is at the origin, one vertex is on the positive \(y\)-axis, one vertex is on the positive \(x\)-axis, and one vertex lies on the curve \(y=e^{-x}\).

Find the largest possible area of such a rectangle.

Solution

This question involves optimization. So in particular, we're going to be looking for extreme values of a function. This corresponds to when the derivative of the function is \(0\) or does not exist. Here is a possible solution:

Any rectangle of this form has a vertex at the point \((0,0)\) and a vertex on the positive \(x\)-axis, say at \((x,0)\), for some \(x\gt 0\). Once we've fixed these two vertices, the other two vertices are decided. To form a rectangle, another vertex must lie above the point \((x,0)\) on the graph \(y=e^{-x}\); this point must be \((x,e^{-x})\). Similarly, the final vertex must lie above the origin at \((0,e^{-x})\). We see that the rectangle has width \(x\) and height \(e^{-x}\).

If we let A(x) denote the area of this particular rectangle, the area of this rectangle is given by the formula

\[A(x) = \underbrace{\quad x\quad}_{\text{width}} \underbrace{\quad e^{-x}\quad}_{\text{height}}\]

This function allows us to compute the area of any of these rectangles given the \(x\)-value of the point lying on the \(x\)-axis.

We're asked to find the largest possible area of such a rectangle. So we need to find the maximum value of the area function \(A(x)= xe^{-x}\) for \(x \geq 0\). To do so, we need to consider rates of change.

Consider the derivative of the area function, \(A'(x)\).

Using the product rule and the chain rule, we find

\[\begin{align*} A'(x) & = x \dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^{-x}\Big) + e^{-x}\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(x\Big), & \text{using the product rule} \\ & = x ~(-e^{-x}) +e^{-x}~(1), & \text{using the chain rule on }\dfrac{d}{dx}\Big(e^{-x}\Big)\\ & = e^{-x} - x e^{-x} \\ & = e^{-x}(1-x) \end{align*}\]

Since \(e^{-x} \gt 0\) for all \(x\) (since \(e^{-x}\) is an exponential), we have \(A'(x)=0\) if and only if \(1-x=0\), so \(x=1\).

Therefore we have a local extreme at \(x=1\). Our hope is that this is indeed a maximum.

Since \(A'(x) \gt 0\) for \(x\lt 1\) and \(A'(x) \lt 0\) for \( x \gt 1\), \(A(x)\) has a local maximum at \(x=1\).

(In fact, the absolute maximum of \(A(x)\) occurs at \(x=1\).)

Calculating the area of the rectangle corresponding to \(x=1\), we get

\[ A(1) = (1)e^{-1} = \dfrac{1}{e} \approx 0.368 \]

Therefore, the largest area that can be achieved is \(\dfrac{1}{e} \approx 0.368\) units squared.

Note: No matter how large we make the width of the rectangle, we cannot obtain an area larger than the area acheived with a width of \(1\). Does this make sense? How would this question change if, instead, we were asked to maximize the perimeter of the rectangle?