Prime and Composite Numbers

Factors Review

A factor of a number is an integer that divides evenly into that number.

Example

The factors of \(12\) are \(1\), \(2\), \(3\), \(4\), \(6\), and \(12\).

How did we find these factors? When we are looking for factors that divide evenly into a number, we often consider what pairs of numbers multiply together to give us that number. For example,

\(3 \times 4 = 12\)

\(3\) and \(4\) are factors of \(12\)

Prime and Composite Numbers

When we consider the factors of \(13\), we find that there are only two of them: \(1\) and \(13\). No other integers will divide evenly into \(13\).

This is quite the contrast to the factors of \(12\), where there were a total of six factors. Recall the factors of \(12\) are \(1\), \(2\), \(3\), \(4\), \(6\), and \(12\).

A number, like \(13\), that only has two factors, \(1\) and itself, is called a prime number.

A prime number is a positive integer whose only positive divisors are \(1\) and itself.

A prime number has exactly two factors: \(1\) and itself.

\(12\) is clearly not a prime number because it has more than two factors. A number like \(12\) is called a composite number.

A composite number is a positive integer that can be divided evenly by at least one number other than \(1\) and itself.

A composite number has more than two factors.

Let's look at a few examples of both prime and composite numbers.

Some examples of prime numbers are \(2\), \(3\), \(5\), and \(7\).

| Prime Number |

Factors |

| \(2\) |

\(1, ~2\) |

| \(3\) |

\(1, ~3\) |

| \(5\) |

\(1, ~5\) |

| \(7\) |

\(1,~ 7\) |

Some examples of composite numbers are \(4\), \(6\), \(8\), and \(9\).

| Composite Number |

Factors |

| \(4\) |

\(1,~ 2, ~4\) |

| \(6\) |

\(1,~ 2,~ 3,~ 6\) |

| \(8\) |

\(1,~ 2,~ 4, ~8\) |

| \(9\) |

\(1,~ 3,~ 9\) |

Example 1

Is \(27\) a prime number or a composite number?

Solution

To decide whether \(27\) is a prime or composite number, we can consider whether \(27\) has exactly two factors or more than two factors.

Prime

\(\implies\) exactly two factors

Composite

\(\implies\)more than two factors

Some factors of \(27\) include:

Since every positive integer has the factors of \(1\) and itself.

So we want to consider if there is any other number that divides evenly into \(27\) other than \(1\) and \(27\), itself.

Since \(3\) divides evenly into \(27\).

This means \(3\) is also a factor of \(27\).

Therefore, \(27\) is a composite number because it has more than two factors.

In fact, \(27\) has four total factors. The factors of \(27\) are \(1\), \(3\), \(9\), and \(27\).

Example 2

Is \(11\) a prime number or a composite number?

Solution

We can consider whether \(11\) has any factors other than \(1\) and \(11\) itself.

If it doesn't, it will be a prime number. And if it does, it will be a composite number.

Prime

\(\implies\)exactly two factors

Composite

\(\implies\)more than two factors

It is sometimes easiest to start at \(2\) and work our way up logically removing integers that do not divide into \(11\). \(2\) does not divide evenly into \(11\) since \(2\) only divides into even numbers.

\(2\) ✘

This is the same for all even numbers, so \(4\), \(6\), \(8\), and \(10\) will not divide evenly into \(11\) either.

\(4\) ✘

\(6\) ✘

\(8\) ✘

\(10\) ✘

Continuing with the odd numbers, neither \(3\) nor \(5\) divide evenly into \(11\).

\(7\) is more than half of \(11\), so \(7\) is too large to divide evenly into \(11\). We can conclude that any number larger than \(7\) will also not divide evenly into \(11\).

\(7\) ✘

\(8\) ✘

\(9\) ✘

\(10\) ✘

The only factors of \(11\) are \(1\) and \(11\).

Therefore, \(11\) is a prime number because it only has two factors, \(1\) and itself.

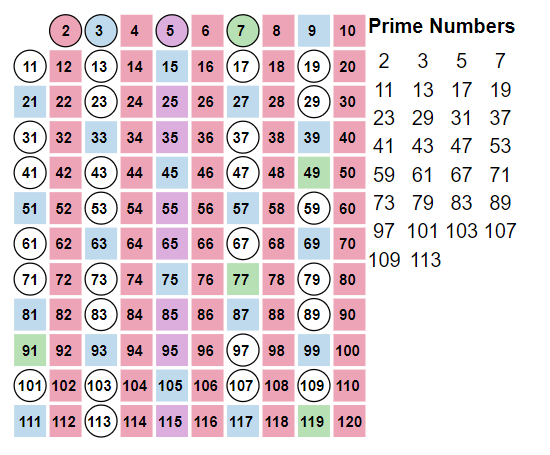

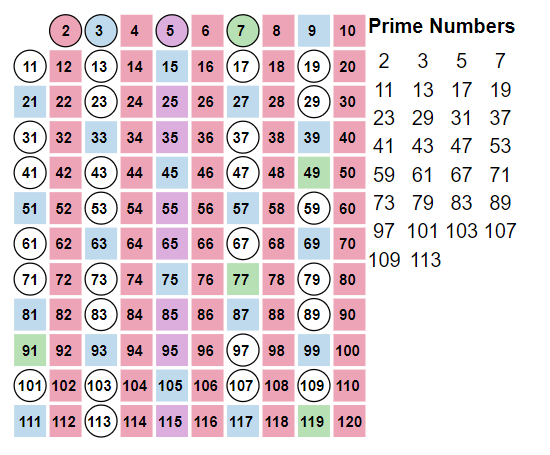

Try This Problem Revisited

Now that we are more comfortable with the prime and composite numbers, let's have a look at the Try This problem from earlier in the lesson.

You may have noticed some patterns in the chart. Here's how it works.

We start with the smallest prime number, \(2\).

We realize that every multiple of \(2\), or every number that \(2\) divides evenly into, must be a composite number.

So all of the multiples of \(2\) become highlighted.

Next, we follow the same process with the next smallest number that is not highlighted.

This next number is \(3\), and all of the multiples of \(3\) become highlighted.

Next, we follow the same process with the next smallest number that is not highlighted:

\(5\) and all of the multiples of \(5\).

Next up is \(7\) and all of the multiples of \(7\).

This process continues until all of the numbers have been highlighted or remain unhighlighted.

When complete, all of the composite numbers are highlighted since they are all multiples of other numbers. All of the circled numbers are prime numbers.

Image Description

The prime numbers less than \(120\) include

\(\begin{align*}& 2,~3,~5,~7,~11,~13,~17,~19,~23,~29,~31,~37,~41,~43,~47,~53,~59,\\ & 61,~67,~71,~73,~79,~83,~89,~97,~101,~103,~107,~109,~113\end{align*}\)

Source: Sieve - Ricordisamoa. (2007, November 7). Sieve of Eratosthenes animation. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Visualizing this process helps us to understand the differences between prime numbers and composite numbers. Since we'll be using prime numbers in future lessons, it is helpful to familiarize yourself with some of the prime numbers, especially those that are less than \(30\).

The Sieve of Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes was a Greek mathematician and all around scholar who, 2200 years ago, created the Sieve of Eratosthenes.

The Sieve shows all prime and composite numbers up to a given point. For the Sieve that we have here, we stop at \(120\).

Source: Sieve - Ricordisamoa. (2007, November 7). Sieve of Eratosthenes animation. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Used under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Check Your Understanding 1

Question

For each number below, determine whether it is a prime number or a composite number.

- \(10\)

- \(49\)

- \(7\)

- \(11\)

Answer

- \(10\) is composite.

- \(49\) is composite.

- \(7\) is prime.

- \(11\) is prime.

Feedback

Prime number numbers have only two factors, \(1\) and the number itself. Composite numbers have more than two factors. Listing the factors of each number gives us the following:

| Number |

Factors |

| \(10\) |

\(1,~2,~5,~10\) |

| \(49\) |

\(1,~7,~49\) |

| \(7\) |

\(1,~7\) |

| \(11\) |

\(1,~11\) |

Is \(1\) Prime?

You may have been wondering about the number \(1\). Is \(1\) a prime number? Based on our definition of a prime number, \(1\) seems like it would fit, since \(1\) can be divided evenly by \(1\) and itself.

A prime number is a positive integer whose only positive divisors are \(1\) and itself.

A prime number has exactly two factors: \(1\) and itself.

The number \(1\) has only one factor. So it doesn't fit the second part of our definition — that a prime number has exactly two factors.

Therefore, \(1\) is not considered to be a prime number.