Finding Equal Angles

Consider the following two parallel lines, \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\), that intersect the transversal \(\overleftrightarrow{EF}\) at \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively, such that \(\angle XYD\) is equal to \(45^\circ\).

Since \(\angle EXB\) corresponds to \(\angle XYD\) and since corresponding angles are equal, we know that \(\angle EXB\) is equal to \(45\) degrees, as well.

What other angles are equal to \(45^\circ\) in this diagram, and how do you know?

Well, we can see that \(\angle AXY\) is opposite to \(\angle EXB\). And since opposite angles are equal, \(\angle AXY\) is equal to \(45^\circ\).

Similarly, \(\angle CYF\) and \(\angle XYD\) are opposite angles. So \(\angle CYF\) is also equal to \(45^\circ\).

In this diagram, we see opposite angles, and we see corresponding angles.

But we also see another pair of angles that are equal, namely \(\angle AXY\) and \(\angle XYD\). These two angles are not opposite, nor are they corresponding. So we have to come up with another name to describe the relationship.

Alternate Angles

A pair of angles that are formed between the pair of parallel lines on opposite sides of the transversal are called alternate angles.

In this diagram, angles \(c\) and \(e\) are alternate angles, as are angles \(d\) and \(f\).

Alternate Angles

- \(c\) and \(e\)

- \(d\) and \(f\)

To help us remember, sometimes alternate angles are nicknamed Z angles, because of the Z-like shape formed by the intersecting lines in transversal.

Note that depending on the location of the alternate angles, the Z shape might be reflected.

Important Fact

So let's jump back to our diagram of two parallel lines in a transversal again. We showed that if \(\angle XYD\) is equal to \(45^\circ\), then the alternate angle, \(\angle AXY\), is also equal to \(45 ^\circ\).

If instead \(\angle XYD\) is equal to \(90^\circ\), then through similar steps, we can show that \(\angle EXB\) is equal to \(90^\circ\), because it corresponds to \(\angle XYD\).

And then that \(\angle AXY\) is equal to \(90^\circ\), because it is opposite \(\angle EXB\). Again, we have two alternate angles, \(\angle AXY\) and \(\angle XYD\), that are equal.

As a third and final example, if \(\angle XYD\) is equal to \(110^\circ\), we can show that \(\angle EXB\) is equal to \(110^\circ\), because it corresponds to \(\angle XYD\).

And then go ahead and show that \(\angle AXY\) is equal to \(110^\circ\), because it is opposite \(\angle EXB\). Again, the two alternate angles, \(\angle AXY\) and \(\angle XYD\), are equal.

You should be able to convince yourself that no matter what the measure of \(\angle XYD\), its alternate angle, \(\angle AXY\), will always be equal in measure. It turns out that this is true for any pair of alternate angles.

Alternate angles are equal.

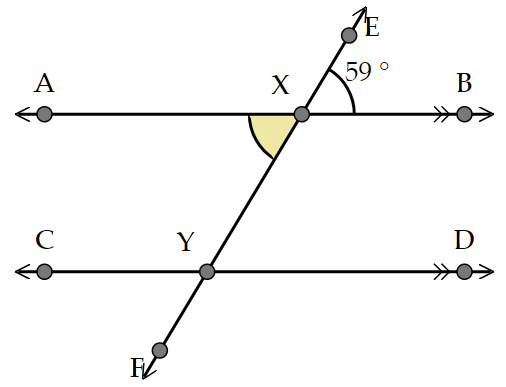

Check Your Understanding 3

Question

What is the value of \(\angle AXY\)? Explain how you know.

Answer

\(\angle AXY = 59^\circ\), since \(\angle AXY\) is opposite to \(\angle BXE\).

Feedback

Since \(\angle AXY\) is opposite to \(\angle BXE\), and since opposite angles are equal, we know that \(\angle AXY = 59^\circ\).

Recognizing More Supplementary Angles

So far, we have found all angles in the following diagram that are equal to \(110^\circ\).

But what do we know about the angles that are left? Well, using our knowledge of straight angles, we can determine that \(\angle BXY\) is equal to \(70^\circ\), because it is supplementary to \(\angle AXY\). Notice that there is now a pair of angles that are located between the parallel lines on the same side of the transversal. We call this pair of angles co-interior angles.

We call this pair of angles co-interior angles.

Co-Interior Angles

Recall our diagram:

Notice angle \(c\) and \(f\) are co-interior angles, as are angles \(d\) and \(e\).

To help us remember, sometimes co-interior angles are nicknamed C angles, because of the C shape formed by the intersecting lines and the transversal.

Co-Interior Angles

- \(c\) and \(f\)

- \(d\) and \(e\)

Now depending on the location of the co-interior angles, the C shape might be reflected.

Co-interior angles are supplementary.

Example 2

Two parallel lines, \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{CD}\), intersect the transversal \(\overleftrightarrow{EF}\) at \(X\) and \(Y\), respectively, such that \(\angle XYD\) is equal to \(112^\circ\).

Find the measures of the four angles created where \(\overleftrightarrow{AB}\) and \(\overleftrightarrow{EF}\) intersect.

Solution

Now, there are many ways to find the measures of the unknown angles, and we're going to follow just one of these paths in the solution.

First, we might notice that the lines forming \(\angle XYD\) and \(\angle EXB\) make an F shape, and so these angles are corresponding angles. We know that \(\angle EXB\) is equal to \(112^\circ\) since it corresponds to \(\angle XYD\), and we know the corresponding angles are equal.

Next, the lines forming angle bxy and \(\angle XYD\) make a C shape. And so these angles are co-interior angles. We know that \(\angle BXY\) is equal to \(68^\circ\) since it is co-interior to \(\angle XYD\), and we know co-interior angles to be supplementary.

The lines forming \(\angle AXY\) and \(\angle XYD\) make a Z shape. And so these angles are alternate angles. Thus, we know that \(\angle AXY\) is equal to \(112^\circ\) since it is alternate to \(\angle XYD\), and we know alternate angles to be equal.

Finally, we can find \(\angle AXE\) by recognizing that it is opposite to \(\angle BXY\). We know that \(\angle AXE\) is equal to \(68^\circ\) since it is opposite \(\angle BXY\), and we know opposite angles to be equal.

In summary, we have the following:

- \(\angle EXB = 112^\circ\) (corresponds to \(\angle XYD\))

- \(\angle BXY=68^\circ\) (co-interior to \(\angle XYD\))

- \(\angle AXY = 112^\circ\) (alternate to \(\angle XYD\))

- \(\angle AXE=68^\circ\) (opposite to \(\angle BXY\))

Summary

We have explored some new relationships between a pair of angles formed by two parallel lines and a transversal.

Corresponding angles are equal.

Alternate angles are equal.

Co-interior angles are supplementary.

Remember that these patterns also have nicknames, the F, Z, and C patterns, respectively, which come from the shape formed by the intersecting lines in the transversal. But make sure not to forget about the properties of opposite, complementary, and supplementary angles from before, because they're also helpful when solving problems involving angles.

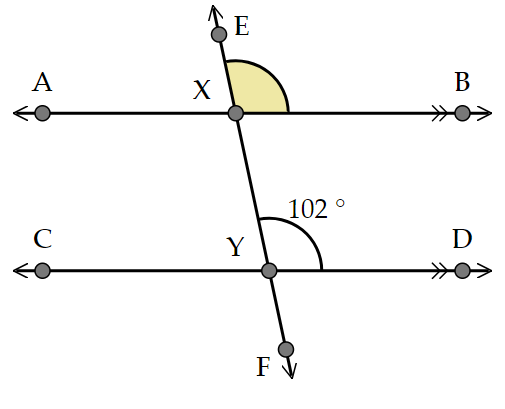

Check Your Understanding 4

Question

What is the value of \(\angle BXE\)? Explain how you know.

Answer

\(\angle BXE = 102^\circ\), since \(\angle BXE\) is corresponding to \(\angle DYX\).

Feedback

Since \(\angle BXE\) corresponds to \(\angle DYX\), and since corresponding angles are equal, we know that \(\angle BXE = 102^\circ\).