Relations and Functions Alternative Format

Lesson Part 1

In This Module

In this module, we will be looking at a variety of topics. Some of the topics will be review for you and other topics may be topics you've never seen before. So for some students, you may wish to go right to the end and look at the Maple quiz and the exercises. For other students, you may want to just jump ahead to things that you're not familiar with. For other students, just for the general sake of review, you may want to just progress through the module.

- We will introduce relations and functions.

- We will represent relations and functions using set notation, mapping diagrams, and graphs.

- We will introduce the vertical line test.

- We will introduce domain and range.

- We will introduce function notation.

- We will introduce composite functions.

Relations and Functions

A relation is a set of ordered pairs.

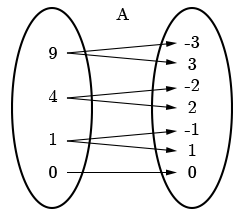

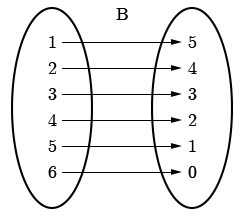

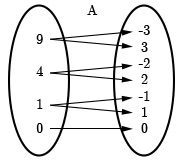

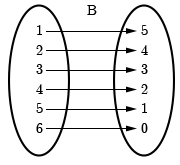

Two possible sets of ordered pairs are listed. I've entitled one A and I've entitled the other B.

Let \( A = \{(9, -3), (4, -2), (1, -1), (0, 0), (1, 1), (4, 2), (9, 3)\} \).

Let \( B = \{(1, 5), (2, 4), (3, 3), (4, 2), (5, 1), (6, 0)\} \).

The elements in each set have been listed using set notation. We enclose the ordered pairs in brace brackets and we list either the entire set or a description of the entire set. In this case, we've listed the entire set.

A function is a relation, a set of ordered pairs \((x,y)\), in which for every \( x \) value, there is only one \( y \) value.

By definition, \( A \) is not a function, whereas \( B \) is a function.

We can represent \(A\) and \(B\) using mapping diagrams.

Since at least one \(x\)-value maps to more than one \(y\)-value, \(A\) is not a function. For example, the \(x\)-coordinate \(9\) gives the \(y\)-coordinates \(-3\) and \(3\).

Since each \(x\)-value maps to exactly one \(y\)-value, \(B\) is a function.

Check Your Understanding A

This question is not included in the Alternative Format, but can be accessed in the Review section of the side navigation.

Representing Relations and Functions Graphically

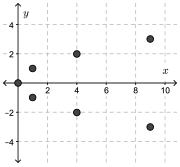

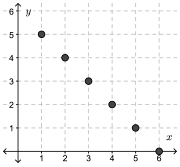

We have represented \(A\) and \(B\) using set notation and mapping diagrams for each set.

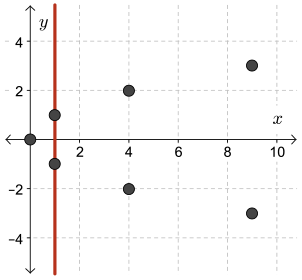

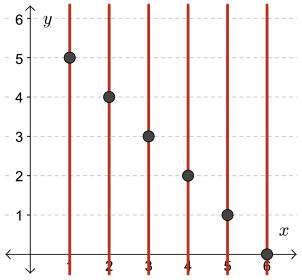

We can also represent both sets, \(A\) and \(B\), on a graph.

\(A=\{(9,-3),(4,-2),(1,-1),(0,0),(1,1),(4,2),(9,3)\}\)

\(B=\{(1,5),(2,4),(3,3),(4,2),(5,1),(6,0)\}\)

How can we tell graphically whether or not a relation is a function?

The Vertical Line Test

If a vertical line can be drawn anywhere on a graph so that it passes through two or more points on a relation, then the relation is not a function.

However, if no vertical line can be drawn that passes through more than one point on a relation, then the relation is a function.

This is called the vertical line test.

\(A=\{(9,-3),(4,-2),(1,-1),(0,0),(1,1),(4,2),(9,3)\}\)

A vertical line can be drawn through the two points, \((1,-1)\) and \((1,1)\). Therefore, \(A\) is not a function.

\(B=\{(1,5),(2,4),(3,3),(4,2),(5,1),(6,0)\}\)

No vertical line can be drawn through any two points on \(B\). Therefore, \(B\) is a function.

Check Your Understanding B

This question is not included in the Alternative Format, but can be accessed in the Review section of the side navigation.

Lesson Part 2

Domain and Range

\(A=\{(9,-3),(4,-2),(1,-1),(0,0),(1,1),(4,2),(9,3)\}\)

\(B=\{(1,5),(2,4),(3,3),(4,2),(5,1),(6,0)\}\)

The set of all possible values of the independent variable, \(x\), is called the domain.

The set of all possible values of the dependent variable, \(y\), is called the range.

For \(A=\{(9, -3), (4, -2), (1, -1), (0, 0), (1, 1), (4, 2), (9, 3)\} \) the domain is \(\{0,1,4,9\} \), and the range is \(\{-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3\}\).

For \(B=\{(1, 5), (2, 4), (3, 3), (4, 2), (5, 1), (6, 0)\}\) the domain is \(\{1,2,3,4,5,6\} \), and the range is \(\{0,1,2,3,4,5\}\).

Using the terminology of domain and range, a function is a relation in which each element in the domain corresponds to exactly one element in the range.

Example 1

State the domain and range of the following. State, with justification, whether or not each relation is a function.

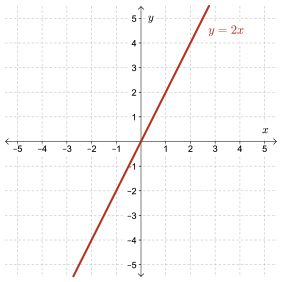

Part A

Solution

This relation is a function since it passes the vertical line test.

The domain is the set of real numbers. We write this as follows:

Domain is \(\{x\mid x\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

We read this, “The domain is the set of \(x\) values such that \(x\) is an element of the set of real numbers.”

The range is the set of real numbers. We write this as follows:

Range is \(\{y\mid y\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

In set notation, the symbol, “\(\mid\)”, is a mathematical short form for “such that” and the symbol, “\(\in\)”, stands for “element of.”

The reason we make the note here about the symbol which is the vertical line is, in different contexts, this symbol means other things. But in sets, the vertical line means "such that."

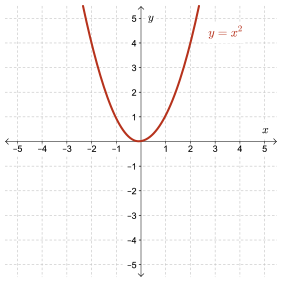

Part B

Solution

This relation is a function since it passes the vertical line test.

The domain is the set of real numbers. There is no real number which cannot be squared. We write this as follows:

Domain is \(\{x\mid x\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

The range is the set of real numbers which are greater than or equal to zero since squaring any real number results in a real number that is positive or zero. We write this as follows:

Range is \(\{y\mid y \ge 0, y\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

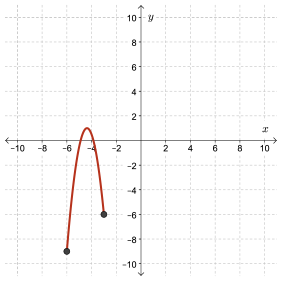

Part C

Solution

This relation is a function since it passes the vertical line test.

This example is different from the previous example in that there are definite starting and ending points on the graph.

I will use the phrase “it would appear,” because we're not quite sure if the point shown on the graph is \((-6, -9)\), or if it's \(-6.1\) and a slightly different \(y\) coordinate. So rather than say that it is \(-6\) to \(-3\) for the domain, we just add that little phrase “it would appear.”

It would appear from the graph that the domain is the set of real numbers from \(-6\) to \(-3\), inclusive. We write this as follows:

Domain is \(\{x\mid -6\le x\le -3,x\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

It would appear from the graph that the range is also restricted to real numbers between \(-9\) and \(1\), inclusive. We write this as follows:

Range is \(\{y\mid -9\le y\le 1, y\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

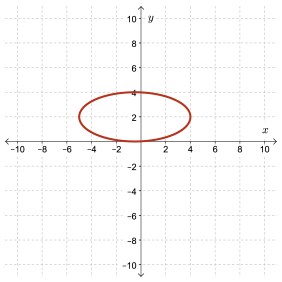

Part D

Solution

This relation is not a function since it fails the vertical line test. For example, a vertical line drawn along the \(y\)-axis intersects the relation twice.

It would appear from the graph that the domain is the set of real numbers from \(-5\) to \(4\), inclusive. We write this as follows:

Domain is \(\{x\mid -5\le x\le 4,x\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

It would appear from the graph that the range is also restricted to real numbers between \(0\) and \(4\), inclusive. We write this as follows:

Range is \(\{y\mid 0\le y\le 4, y\in \mathbb{R}\}\)

Check Your Understanding C and D

These questions are not included in the Alternative Format, but can be accessed in the Review section of the side navigation.

Lesson Part 3

At this point, we will introduce a special notation used with functions, function notation.

Function Notation

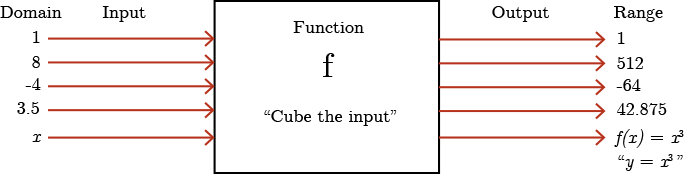

Think of a function as a machine. The machine inputs acceptable values from the domain, and then performs some operation to produce an output value in the range.

In the function machine illustrated below, an input is provided and the function cubes the input to produce an output. We use a special notation called function notation to represent this. In this case, \(f(x)=x^3\).

We read \(f(x)\) as “\(f\) at \(x\)” or “\(f\) of \(x\)”.

So, \(f(8)\) tells the function to cube \(8\) producing an output of \(512\). Therefore, \(f(8)=512\).

\(f(x)=x^3\) can be written as the equation \(y=x^3\); \(f(x)\) and \(y\) are interchangeable.

Function notation is helpful in illustrating the value that is being substituted in the function for \(x\) or for the independent value.

If \(f(x)=x^3\), then we know that \(f(3.5)\) is asking us to evaluate the function when \(x=3.5\). It follows that \(f(3.5)=3.5^3=42.875\).

Example 2 — Part A

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

i. Evaluate \(f(-6)\)

ii. Evaluate \(g(-3)\)

Solution

i. Since \(f(x)=2x+3\),

\[ \begin{align*} f(-6) &= 2(-6)+3 \\ &= -9 \end{align*} \]

ii. Since \(g(x)=x^2+4x\),

\[ \begin{align*} g(-3) &= (-3)^2+4(-3) \\ &= 9-12 \\ &= -3 \end{align*} \]

Check Your Understanding E

This question is not included in the Alternative Format, but can be accessed in the Review section of the side navigation.

Example 2 — Part B

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

For what value(s) of \(x\) does \(f(x)=-8\)?

Solution

We are looking for the value of \(x\) which, when substituted into the function, produces an output value of \(-8\).

Since \(f(x)=-8\),

\[ \begin{align*} 2x+3 &= -8 \\ 2x &= -11 \\ x &= -\frac{11}{2} \end{align*} \]

Therefore, when \(x=-\dfrac{11}{2}\), \(f\left(-\dfrac{11}{2}\right)=-8\).

Example 2 — Part C

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

For what value(s) of \(x\) does \(f(x)=g(x)\)?

Solution

\[ \begin{align*} f(x) &= g(x) \\ 2x+3 &= x^2+4x \\ 0 &= x^2+2x-3 \\ 0 &= (x+3)(x-1) \end{align*} \]

Therefore, \(x=-3\) or \(x=1\).

It follows that \(f(-3)=g(-3)=-3\) and \(f(1)=g(1)=5\).

Example 2 — Part D

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

Evaluate \(f(g(5))\).

Solution

We always evaluate the work inside brackets first.

So in this case, we evaluate \(g(5)\) by substituting \(5\) for \(x\) into \(g(x)\), and then substitute that result for \(x\) into \(f(x)\).

Since \(g(x)=x^2+4x\),

\[ \begin{align*} g(5) &= (5)^2+4(5) \\ &= 25+20 \\ &= 45 \end{align*} \]

Now,

\[ \begin{align*} f(g(5)) &= f(45) \\ &= 2(45)+3 \\ &= 93 \end{align*} \]

Therefore, \(f(g(5))=93\).

Example 2 — Part E

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

Simplify \(f(g(x))\).

Solution

Since \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\),

\[ \begin{align*} f(g(x)) &= f(x^2+4x) \\ &= 2(x^2+4x)+3 \\ &= 2x^2+8x+3 \end{align*} \]

Example 2 — Part F

Let \(f(x)=2x+3\) and \(g(x)=x^2+4x\).

Simplify \(g(f(x))\).

Solution

Since \(g(x)=x^2+4x\) and \(f(x)=2x+3\),

\[ \begin{align*} g(f(x)) &= g(2x+3) \\ &= (2x+3)^2+4(2x+3) \\ &= 4x^2+12x+9+8x+12 \\ &= 4x^2+20x+21 \end{align*} \]

Generally speaking, \(f(g(x))\not = g(f(x))\).

However, there are functions \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\) for which \(f(g(x)) = g(f(x))\).

These will be investigated in future modules.

Lesson Part 4

The last three examples lead us to a topic in mathematics, which will be pursued in this course or in this set of modules, a topic called composite functions.

Composite Functions

\[f(x)=2x+3\]\[g(x)=x^2+4x\]\[f(g(x))=2x^2+8x+3~~\text{and}~~g(f(x))=4x^2+20x+21\]

\(f(g(x))\) and \(g(f(x))\) are examples of composite functions.

Composition of functions is the process of combining two or more functions where one function is performed first and the result is substituted in place of \(x\) into the next function, and so on. When we substitute one function into another function, we create a composite function.

\(f(g(x))\) is read “\(f\) of \(g\) of \(x\),” or again, we could say “\(f\) at \(g\) at \(x\)”. It is also written \((f\circ g)(x)\).

The idea of composite functions will be developed in other modules of this course.

We will answer questions like, “When is it possible to compose two functions?”, and, “Do two functions exist such that \(f(g(x))=g(f(x))\)?”

Check Your Understanding F

This question is not included in the Alternative Format, but can be accessed in the Review section of the side navigation.

Summary

The concepts introduced in this module may not have been totally new, but they provide some of the basic building blocks for further study of functions.

- We introduced relations and functions.

- We represented relations and functions using set notation, mapping diagrams, and graphs.

- We introduced the vertical line test.

- We introduced domain and range.

- We introduced function notation.

- We introduced composite functions.